7.2 Logarithmic Functions

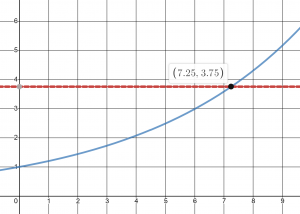

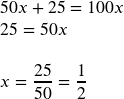

If a location has an R number of 1.2 for coronavirus and they have 1500 hospital beds available. Assuming they are starting with 2000 active cases today and about 20% of coronavirus patients will need a hospital bed, how many weeks will it be before their hospitals are overwhelmed? Remember the exponential function for this was ![]() . The hospitals can handle 1500 patients so we need to know the number of cases the location can handle. 20% of that number is 1500. So:

. The hospitals can handle 1500 patients so we need to know the number of cases the location can handle. 20% of that number is 1500. So:

![]()

![]()

So the location will be overwhelmed after 7500 active cases, to find the number of weeks this will be, we solve the following equation:

![]()

We can divide both sides by 2000:

![]()

While we have set up exponential models and used them to make predictions, you may have noticed that solving exponential equations has not yet been mentioned. The reason is simple: none of the algebraic tools discussed so far are sufficient to solve exponential equations. Consider the equation ![]() above. We can use our calculator to determine that

above. We can use our calculator to determine that ![]() and

and ![]() , so it is clear that x must be some value between 7 and 8 since the function is increasing. We could use technology to create a table of values or graph to better estimate the solution.

, so it is clear that x must be some value between 7 and 8 since the function is increasing. We could use technology to create a table of values or graph to better estimate the solution.

Note that the graph of ![]() intersects with

intersects with ![]() at

at ![]() , so we know that the number of weeks to 7500 cases and thus a requirement of 1500 or more hospital beds is a little over 7 weeks away, which might cause local officials to create mitigating efforts to lower the R number.

, so we know that the number of weeks to 7500 cases and thus a requirement of 1500 or more hospital beds is a little over 7 weeks away, which might cause local officials to create mitigating efforts to lower the R number.

This result is still fairly unsatisfactory, since it would be nice to have a function that gives the answer. None of the functions we have already discussed would work, so we must introduce a new function, named log, as the function that “undoes” an exponential function, like how a square root “undoes” a square. Since exponential functions have different bases, we will define corresponding logarithms of different bases as well.

Logarithm

The logarithm (base b) function, written ![]() , “undoes” exponential function

, “undoes” exponential function ![]() .

.

The statement ![]() is equivalent to the statement

is equivalent to the statement ![]() .

.

Since the logarithm and exponential “undo” each other (in technical terms, they are inverses), the following properties of logs are no surprise.

Properties of Logs: Inverse Properties

Since log is a function, it is most correctly written as ![]() , using parentheses to denote function evaluation, just as we would with

, using parentheses to denote function evaluation, just as we would with ![]() . However, when the input is a single variable or number, it is common to see the parentheses dropped and the expression written as

. However, when the input is a single variable or number, it is common to see the parentheses dropped and the expression written as ![]() .

.

Example Using Inverse Properties of Logs

a. Write these exponential equations as logarithmic equations:

i. ![]()

This is equivalent to ![]()

ii. ![]()

This is equivalent to ![]()

iii. ![]()

This is equivalent to ![]()

b. Write these logarithmic equations as exponential equations:

i. ![]()

This is equivalent to ![]()

ii. ![]()

This is equivalent to ![]()

Try it Now 1

a. Write the exponential equation ![]() as a logarithmic equation.

as a logarithmic equation.

b. Write the logarithmic equation ![]()

By establishing the relationship between exponential and logarithmic functions, we can now solve basic logarithmic and exponential equations by rewriting.

Examples Solving by Rewriting

a.Solve ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

By rewriting this expression as an exponential, ![]() , so

, so ![]()

b. Solve ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

By rewriting this expression as a logarithm, we get ![]()

While this does define a solution, and an exact solution at that, you may find it somewhat unsatisfying since it is difficult to compare this expression to the decimal estimate we made earlier. Also, giving an exact expression for a solution is not always useful – often we really need a decimal approximation to the solution. Luckily, this is a task calculators and computers are quite adept at. Unluckily for us, most calculators and computers will only evaluate logarithms of two bases. Happily, this ends up not being a problem, as we’ll see briefly.

Common and Natural Logarithms

The common log is the logarithm with base 10, and is typically written ![]() .

.

The natural log is the logarithm with base e, and is typically written ![]() .

.

History Note: The reason that natural log is denoted by

History Note: The reason that natural log is denoted by ![]() instead of nl is because it comes from the latin logarithmus naturali which has the initials

instead of nl is because it comes from the latin logarithmus naturali which has the initials ![]() .

.

Example of Common Log

Evaluate ![]() using the definition of the common log.

using the definition of the common log.

| number | number as

exponential |

log(number) |

| 1000 | 103 | 3 |

| 100 | 102 | 2 |

| 10 | 101 | 1 |

| 1 | 100 | 0 |

| 0.1 | 10-1 | -1 |

| 0.01 | 10-2 | -2 |

| 0.001 | 10-3 | -3 |

To evaluate ![]() , we can say

, we can say ![]() , then rewrite into exponential form using the common log base of 10.

, then rewrite into exponential form using the common log base of 10.

![]()

From this, we might recognize that 1000 is the cube of 10, so ![]() .

.

We also can use the inverse property of logs to write ![]()

Try it Now 2

Evaluate ![]()

Example of Natural log

Evaluate ![]() .

.

We can rewrite ![]() as

as ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is a log base

is a log base ![]() we can use the inverse property for logs:

we can use the inverse property for logs: ![]() .

.

Examples of evaluating logs with a a calculator

a. Evaluate ![]() using your calculator or computer.

using your calculator or computer.

Using Excel, we can use the function =log10(500) and it will show up as 2.69897. On a TI or Casio, hit the log key and then 500 enter.

b. Evaluate ![]() using your calculator or computer.

using your calculator or computer.

Using Excel, we can use the function =ln(7) and it will show up as 1.94591. On a TI or Casio, hit the ln key and then 7 enter.

Try it Now 3

Use your calculator or computer to evaluate:

a. ![]()

b. ![]()

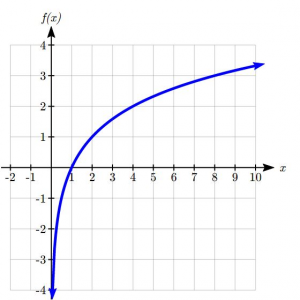

Graphs of Logarithms

Recall that the exponential function produces this table of values:

| x | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| f(x) | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 |

Since the logarithmic function “undoes” the exponential, ![]() produces the table of values:

produces the table of values:

| x | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | |||

| g(x) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

In this second table, notice that

- As the input increases, the output increases.

- As input increases, the output increases more slowly.

- Since the exponential function only outputs positive values, the logarithm can only accept positive values as inputs, so the domain of the log function is

.

. - Since the exponential function can accept all real numbers as inputs, the logarithm can output any real number, so the range is all real numbers or

.

.

Sketching the graph, notice that as the input approaches zero from the right, the output of the function grows very large in the negative direction, indicating a vertical asymptote at ![]() .

.

In symbolic notation we write as ![]() , and as

, and as ![]() .

.

Graphical Features of the Logarithm

Graphically, in the function ![]()

- The graph has a horizontal intercept at (1, 0)

- The graph has a vertical asymptote at

- The graph is increasing and concave down

- The domain of the function is

, or

, or

- The range of the function is all real numbers, or

When sketching a general logarithm with base b, it can be helpful to remember that the graph will pass through the points (1, 0) and (b, 1).

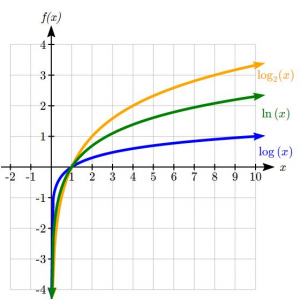

To get a feeling for how the base affects the shape of the graph, examine the graphs below.

Notice that the larger the base, the slower the graph grows. For example, the common log graph, while it grows without bound, it does so very slowly. For example, to reach an output of 8, the input must be 100,000,000.

Another important observation made was the domain of the logarithm. Like the reciprocal and square root functions, the logarithm has a restricted domain which must be considered when finding the domain of a composition involving a log.

Example Finding the Domain of a Logarithmic Function

Find the domain of the function ![]()

The logarithm is only defined when the input is positive, so this function will only be defined when ![]() . Solving this inequality,

. Solving this inequality,

![]()

![]()

The domain of this function is ![]() , or in interval notation

, or in interval notation ![]()

Logarithm Properties

To utilize the common or natural logarithm functions to evaluate expressions like , we need to establish some additional properties.

Properties of Logs: Exponent Property

![]()

To show why this is true, we offer a proof.

Since the logarithmic and exponential functions are inverses, ![]()

So ![]()

Utilizing the exponential rule that states ![]() :

:

![]()

So then ![]()

Again utilizing the inverse property on the right side yields the result

![]()

Examples using the Exponent Property of Logs

a. Rewrite ![]() using the exponent property for logs.

using the exponent property for logs.

Since ![]() ,

,

![]()

b. Rewrite ![]() using the exponent property for logs.

using the exponent property for logs.

Using the property in reverse, ![]()

Try it Now 4

Rewrite using the exponent property for logs: ![]() .

.

The exponent property allows us to find a method for changing the base of a logarithmic expression.

Properties of Logs: Change of Base

![]()

Proof:

Let ![]() . Rewriting as an exponential gives

. Rewriting as an exponential gives ![]() . Taking the log base c of both sides of this equation gives

. Taking the log base c of both sides of this equation gives

![]()

Now utilizing the exponent property for logs on the left side,

![]()

Dividing, we obtain

![]()

or replacing our expression for x,

![]()

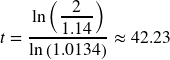

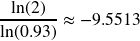

With this change of base formula, we can finally find a good decimal approximation to our question from the beginning of the section.

Examples using Change of Base Formula

a. Solve ![]()

Rewrite this in exponential form:

![]()

Now use change of base with natural log.

![]() which is very close to the answer we got from the graph.

which is very close to the answer we got from the graph.

b. Evaluate ![]() using the change of base formula.

using the change of base formula.

We can rewrite this expression using any other base. If our calculators are able to evaluate the common logarithm, we could rewrite using the common log, base 10.

![]()

While we were able to solve the basic exponential equation ![]() by rewriting in logarithmic form and then using the change of base formula to evaluate the logarithm, the proof of the change of base formula illuminates an alternative approach to solving exponential equations.

by rewriting in logarithmic form and then using the change of base formula to evaluate the logarithm, the proof of the change of base formula illuminates an alternative approach to solving exponential equations.

Solving Exponential Equations

- Isolate the exponential expression when possible

- Take the logarithm of both sides (it does not matter if you use common or natural logs)

- Utilize the exponent property for logarithms to pull the variable out of the exponent

- Use algebra to solve for the variable

Examples Solving an Exponential Equation

a. Solve ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

Using this alternative approach, rather than rewrite this exponential into logarithmic form, we will take the logarithm of both sides of the equation. Since we often wish to evaluate the result to a decimal answer, we will usually utilize either the common log or natural log. For this example, we’ll use the natural log:

![]()

Use the exponent property for logs:

![]()

![]()

b. If the population of India t years after 2008 is modeled according to the function ![]() . If the population continues following this trend, when will the population reach 2 billion?

. If the population continues following this trend, when will the population reach 2 billion?

We need to solve for the ![]() so that

so that ![]()

![]()

Divide by 1.14 to isolate the exponential expression:

![]()

Take the logarithm of both sides of the equation:

![]()

Apply the exponent property on the right side:

![]()

Divide both sides by ![]() :

:

years

years

If this growth rate continues, the model predicts the population of India will reach 2 billion about 42 years after 2008, or approximately in the year 2050.

Try it Now 5

Solve ![]()

Additional Properties of Logarithms

Some situations cannot be addressed using the properties already discussed. For these, we need some additional properties.

Properties of Logs

Sum of Logs Property:

![]()

Difference of Logs Property:

![]()

It’s just as important to know what properties logarithms do not satisfy as to memorize the valid properties listed above. In particular, the logarithm is not a linear function, which means that it does not distribute:

It’s just as important to know what properties logarithms do not satisfy as to memorize the valid properties listed above. In particular, the logarithm is not a linear function, which means that it does not distribute: ![]() .

.

With these properties, we can rewrite expressions involving multiple logs as a single log, or break an expression involving a single log into expressions involving multiple logs.

Examples using the Sum and Difference Properties of Logs

a. Write ![]() as a single logarithm.

as a single logarithm.

Using the sum of logs property on the first two terms,

![]()

This reduces our original expression to ![]()

Then using the difference of logs property,

![]()

b. Evaluate ![]() without a calculator by first rewriting as a single logarithm.

without a calculator by first rewriting as a single logarithm.

On the first term, we can use the exponent property of logs to write

![]()

With the expression reduced to a sum of two logs, ![]() ,

,

we can utilize the sum of logs property:

![]()

Since ![]() , we can evaluate this log without a calculator:

, we can evaluate this log without a calculator:

![]()

c. Rewrite ![]() as a sum or difference of logs.

as a sum or difference of logs.

First, noticing we have a quotient of two expressions, we can utilize the difference property of logs to write ![]()

Then seeing the product in the first term, we use the sum property:

![]()

Finally, we could use the exponent property on the first term:

![]()

Try it Now 6

Without a calculator evaluate by first rewriting as a single logarithm:

![]()

Log properties in solving equations

The logarithm properties often arise when solving problems involving logarithms.

Example Using Log Properties to Solve Equations

Solve ![]() .

.

In order to rewrite in exponential form, we need a single logarithmic expression on the left side of the equation. Using the difference property of logs, we can rewrite the left side:

![]()

Rewriting in exponential form reduces this to an algebraic equation:

![]()

Solving:

Checking this answer in the original equation, we can verify there are no domain issues, and this answer is correct.

Try it Now 7

Solve ![]() .

.

Try it Now Answer

-

- a.

b.

b.

- 6

- a. 2.39794 b. -0.22314

- 5

- 12

- a.

Media Attributions

- 72example1

- history-clipart-scroll-4-transparent is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 72example2

- 72example3

- warningsign