5.4 Roots of Polynomials

This section is remixed from, Precalculus: An Investigation of Functions by Lippman and Rasmussen, licensed by Creative Commons 4.0 CC-BY-SA

In the last section, we limited ourselves to finding the intercepts, or zeros, of polynomials that factored simply, or we turned to technology. In this section, we will look at algebraic techniques for finding the zeros of polynomials like ![]() .

.

Long Division

In the last section we saw that we could write a polynomial as a product of factors, each corresponding to a horizontal intercept. If we knew that x = 2 was an intercept of the polynomial , we might guess that the polynomial ![]() could be factored as

could be factored as ![]() . To find that “something,” we can use polynomial division.

. To find that “something,” we can use polynomial division.

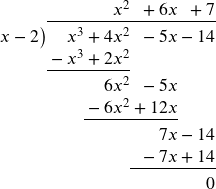

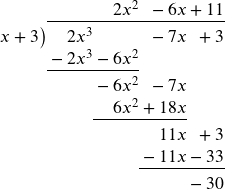

Examples of Polynomial Long Division

Divide ![]() by

by ![]()

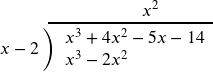

Start by writing the problem out in long division form

![]()

Now we divide the leading terms: ![]() . It is best to align it above the same-powered term in the dividend. Now, multiply that

. It is best to align it above the same-powered term in the dividend. Now, multiply that ![]() by

by ![]() and write the result below the dividend.

and write the result below the dividend.

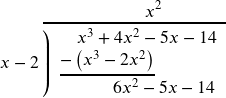

Now subtract that expression from the dividend.

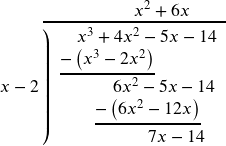

Again, divide the leading term of the remainder by the leading term of the divisor, ![]() . We add this to the result, multiply 6x by x-2, and subtract.

. We add this to the result, multiply 6x by x-2, and subtract.

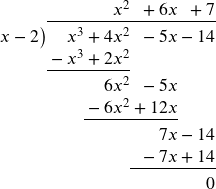

Repeat the process one last time.

This tells us ![]() divided by

divided by ![]() is

is ![]() , with a remainder of zero. This also means that we can factor

, with a remainder of zero. This also means that we can factor ![]() as

as ![]() .

.

This gives us a way to find the intercepts of this polynomial. ![]() cannot be factored, but we could use the quadratic formula to find the roots.

cannot be factored, but we could use the quadratic formula to find the roots.

![]() . So all three roots are

. So all three roots are ![]() and

and ![]()

Try it Now 1

Divide ![]() by

by ![]() using long division.

using long division.

The Factor and Remainder Theorems

When we divide a polynomial, p(x) by some divisor polynomial d(x), we will get a quotient polynomial q(x) and possibly a remainder r(x). In other words, ![]() .

.

Because of the division, the remainder will either be zero, or a polynomial of lower degree than d(x). Because of this, if we divide a polynomial by a term of the form ![]() , then the remainder will be zero or a constant.

, then the remainder will be zero or a constant.

If ![]() , then

, then ![]() , which establishes the Remainder Theorem.

, which establishes the Remainder Theorem.

The Remainder Theorem

If ![]() is a polynomial of degree 1 or greater and c is a real number, then when p(x) is divided by

is a polynomial of degree 1 or greater and c is a real number, then when p(x) is divided by ![]() , the remainder is

, the remainder is ![]() .

.

If ![]() is a factor of the polynomial p, then

is a factor of the polynomial p, then ![]() for some polynomial q. Then

for some polynomial q. Then ![]() , showing c is a zero of the polynomial. This shouldn’t surprise us – we already knew that if the polynomial factors, it reveals the roots.

, showing c is a zero of the polynomial. This shouldn’t surprise us – we already knew that if the polynomial factors, it reveals the roots.

If ![]() , then the remainder theorem tells us that if p is divided by

, then the remainder theorem tells us that if p is divided by ![]() , then the remainder will be zero, which means

, then the remainder will be zero, which means ![]() is a factor of p.

is a factor of p.

The Factor Theorem

If ![]() is a nonzero polynomial, then the real number c is a zero of

is a nonzero polynomial, then the real number c is a zero of ![]() if and only if

if and only if ![]() is a factor of

is a factor of ![]() .

.

Synthetic Division

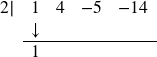

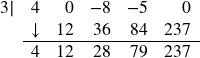

Since dividing by is a way to check if a number is a zero of the polynomial, it would be nice to have a faster way to divide by than having to use long division every time. Happily, quicker ways have been discovered. For more details on how synthetic division works, please see the source material. Recall the first example, we had:

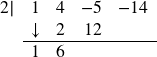

Let’s re-work our division problem using a synthetic division tableau to see how it greatly streamlines the division process. To divide ![]() by

by ![]() , we write 2 in the place of the divisor and the coefficients of

, we write 2 in the place of the divisor and the coefficients of ![]() in for the dividend. Then “bring down” the first coefficient of the dividend.

in for the dividend. Then “bring down” the first coefficient of the dividend.

![]()

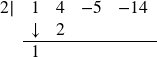

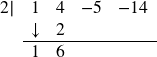

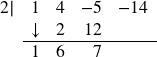

Next, take the 2 from the divisor and multiply by the 1 that was “brought down” to get 2. Write this underneath the 4, then add to get 6.

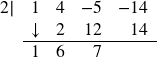

Now take the 2 from the divisor times the 6 to get 12, and add it to the −5 to get 7.

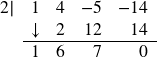

Finally, take the 2 in the divisor times the 7 to get 14, and add it to the −14 to get 0.

The first three numbers in the last row of our tableau are the coefficients of the quotient polynomial. Remember, we started with a third degree polynomial and divided by a first degree polynomial, so the quotient is a second degree polynomial. Hence the quotient is ![]() . The last number is the remainder. Synthetic division is our tool of choice for dividing polynomials by divisors of the form x − c. It is important to note that it works only for these kinds of divisors. Also take note that when a polynomial (of degree at least 1) is divided by x − c, the result will be a polynomial of exactly one less degree. Finally, it is worth the time to trace each step in synthetic division back to its corresponding step in long division.

. The last number is the remainder. Synthetic division is our tool of choice for dividing polynomials by divisors of the form x − c. It is important to note that it works only for these kinds of divisors. Also take note that when a polynomial (of degree at least 1) is divided by x − c, the result will be a polynomial of exactly one less degree. Finally, it is worth the time to trace each step in synthetic division back to its corresponding step in long division.

Examples Using Synthetic Division

a. Use synthetic division to divide ![]() by

by ![]() .

.

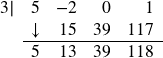

When setting up the synthetic division tableau, we need to enter 0 for the coefficient of x in the dividend. Doing so gives:

Since the dividend was a third degree polynomial, the quotient is a quadratic polynomial with coefficients 5, 13 and 39. Our quotient is ![]() and the remainder is r(x) = 118. This means

and the remainder is r(x) = 118. This means ![]()

We can also write the remainder as a fraction over the divisor:

![]()

It also means that ![]() is not a factor of

is not a factor of ![]() .

.

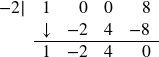

b. Divide ![]() by

by ![]()

For this division, we rewrite ![]() as

as ![]() and proceed as before.

and proceed as before.

The quotient is ![]() and the remainder is zero. Since the remainder is zero,

and the remainder is zero. Since the remainder is zero, ![]() is a factor of

is a factor of ![]() .

.

![]()

Try it Now 2

Divide ![]() by

by ![]() using synthetic division.

using synthetic division.

Using this process allows us to find the real zeros of polynomials, presuming we can figure out at least one root.

Example Finding Roots, given 1

The polynomial ![]() has a horizontal intercept at

has a horizontal intercept at ![]() with multiplicity 2. Find the other intercepts of p(x).

with multiplicity 2. Find the other intercepts of p(x).

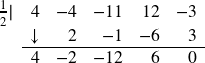

Since ![]() is an intercept with multiplicity 2, then

is an intercept with multiplicity 2, then ![]() is a factor twice. Use synthetic division to divide by

is a factor twice. Use synthetic division to divide by ![]() twice.

twice.

From the first division, we get

![]()

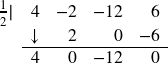

From the second division, we get

![]()

To find the remaining intercepts, we set

![]() and get

and get ![]() .

.

Note this also means

![]() .

.

We could also think of this as

![]() .

.

Try it Now Answers

1.

We can write this division as: ![]()

2.

![]() divided by

divided by ![]() is:

is:

![]()