Model Text: “The Advertising Black Hole”

The Advertising Black Hole[1]

The little girl walked along the brightly lit paths of vibrant colors and enticing patterns. Her close friends watched her as she slowly strolled by. She made sure to inspect each one of them as she moved through the pathways, seeing if there was anything new about them, and wondering which one she was interested in bringing home. She did not know, however, that these so-called friends of hers had the potential to be dangerous and possibly deadly if she spent too much time with them. But she was not aware, so she picked up the colorful box of cereal with her friend Toucan Sam on the outside, put it in the cart and decided that he was her top choice that day. Many children have similar experiences while grocery shopping because numerous large corporations thrive on developing relationships between the young consumer and their products; a regular food item can become so much more than that to children. Due to the bonds that children and products are forming together, early-life weight issues have become an increasingly large issue. While marketing is not the leading or only cause of the obesity epidemic affecting children and teenagers, it does aid in developing and endorsing preferences of unhealthier food options sold in grocery stores, which can lead to higher weights if not controlled.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states that up to 17% of children and adolescents, from ages zero to seventeen, are overweight in the United States. This comes out to approximately 12.7 million young individuals who are affected by the obesity epidemic (“Childhood Obesity”), and there is no projection of this number getting smaller any time soon, as the general population continues to increase. Without any significant changes with how food products are marketed to children and its influence on their food choices, one might predict that there will most likely not be a decline in obesity in kids and teens as populations continue to rise.

Today, large corporations like Oreo, Trix, and Yoplait, amongst others, spend great sums of money marketing to younger generations in hopes that they will want their products and, more importantly, grow an attachment to them. In 2009 alone, companies spent about $1.79 billion on the endeavor (“FTC Releases”). Leading businesses in the food industry spend a lot of money on advertising so that they can establish an emotional connection between their products and fledgling consumers. They try to inspire feelings of familiarity, comfort, “coolness,” adventure, warmth, excitement, and many others that will attract kids and teenagers.

Through trials and studies, leading advertising agencies have found what types of pictures, words, and designs resonate the most with the younger audiences. It is not about selling a product, but creating an experience of joy and wonder for the child. While younger children especially are not aware of the premeditated enticements from the corporate end, they can still become highly engrossed in the products. Some research has shown that a child’s attraction to certain brand characteristics may actually be out of their conscious control (Keller 380).

Young children pick up on things very easily, whether something is specifically taught to them or not, and food preferences are no different. Toddlers as early as two or three can be affected by advertising (McGinnis 376) and can develop bonds to certain products. This shows that even without outside pressures from society or a knowledge of advertising, children can bond with food items just like they do people. This makes sense, as brands are created to be as relatable and welcoming as possible, just like a human being.

With this in mind, developing a specific personality for a brand is extremely important. Many advertising authorities believe that without a brand personality that a company would have an extremely hard time standing out from the crowd. In “Brand Personalities Are Like Snowflakes,” David Aaker, a well-known expert in his field, gives examples of large corporations that use branding to bring a likeability or specific personality type to the business in order to identify with certain groups of people, or to have a larger mass appeal. For example, Betty Crocker comes across as motherly, traditional, and “all-American” (Aaker 20). It makes sense why children and adolescents would develop a fondness for a product that seems homey and loving. If a company succeeds in gaining the interest of a child and creating an emotional connection with them, then it is not impossible or unusual that the individual could stay a brand loyalist into adulthood. But with unhealthy food companies being the source of some of the most intelligent marketing techniques, it is easy for them to entice children to eat foods that are not good for them, all the while making them feel content about their choices.

Once a company comes up with a good branding technique or personality, they can start marketing their products, and the avenues in which companies share them is almost as important as the products themselves. In order for the item to become popular and generate high revenue, they need to reach as many people as possible. If the wrong methods are chosen and there is less of a consumer response, then money has been wasted. While marketing food to children has been very successful in the past, it is even more so now in the 21st century because of the prevalence of mobile devices. Kids and teens are very frequently exposed to advertising through websites, games, or applications that they are using on cell phones, tablets, and laptops. Corporations even collect meta-data from sites or applications that kids access on the device in order to figure out what their preferences are, and to further expose them to ads within their frame of interest, hopefully boosting their sales and likeability through repeated exposure (“Should Advertising”). Television has not been phased out by the internet, however, and it is still a huge contributor to advertising success, accounting for almost half of marketing costs (Harris 409). Movies, magazines and other print sources, sporting events, schools, displays in grocery stores, the boxes themselves, and many other routes are taken in order to create as much of a product “buzz” as possible.

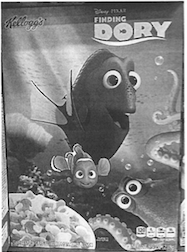

Within these avenues, there are countless techniques that are used in order to gently sway a child or adolescent into wanting a product. Some of these methods are direct, but others are hardly recognizable. I decided to do a little investigating of my own at Fred Meyer’s, one of the leading supermarkets in the Portland area, and found many trends and practices that were used to promote kids’ food. One of the main techniques used is called cross-branding. Also called cross-promoting, this is where a specific product, like cereal for example, will sign an agreement with another company so that they can use each other’s popularity in order to sell more merchandise. The picture shown is a perfect example of this. Kellogg’s teamed up with Disney and Pixar in order to create a one-of-a-kind Finding Dory cereal. This example is actually different than most of the cross-promoting cereals or products, because this is a whole new item made just for the movie; it is not just a picture on a box for a cereal that had already existed. Both companies will come out ahead in this case, since Finding Dory is beloved by children and so will bring revenue to both. Celebrity and sports endorsements are other forms of cross-branding, since they are promoting themselves and the product at the same time. While cartoon characters may be better suited for younger kids, movie and television stars, singers, and athletes help to drawn in the pre-teen and teenage crowds.

Within these avenues, there are countless techniques that are used in order to gently sway a child or adolescent into wanting a product. Some of these methods are direct, but others are hardly recognizable. I decided to do a little investigating of my own at Fred Meyer’s, one of the leading supermarkets in the Portland area, and found many trends and practices that were used to promote kids’ food. One of the main techniques used is called cross-branding. Also called cross-promoting, this is where a specific product, like cereal for example, will sign an agreement with another company so that they can use each other’s popularity in order to sell more merchandise. The picture shown is a perfect example of this. Kellogg’s teamed up with Disney and Pixar in order to create a one-of-a-kind Finding Dory cereal. This example is actually different than most of the cross-promoting cereals or products, because this is a whole new item made just for the movie; it is not just a picture on a box for a cereal that had already existed. Both companies will come out ahead in this case, since Finding Dory is beloved by children and so will bring revenue to both. Celebrity and sports endorsements are other forms of cross-branding, since they are promoting themselves and the product at the same time. While cartoon characters may be better suited for younger kids, movie and television stars, singers, and athletes help to drawn in the pre-teen and teenage crowds.

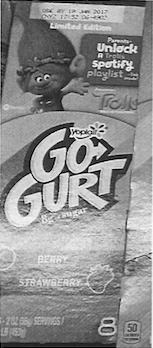

Other identified advertising tools from the packages themselves might include sweepstakes to win prizes, toys inside, free games or applications with purchase, and collecting UPC codes for gifts. The picture shown to the right is another example from my personal research, which shows a Go-Gurt box. It not only shows cross-branding with the movie Trolls, but it also includes something for free. The top right-hand corner displays that inside of the box there is a special link for a free Trolls Spotify playlist. Prizes that used to be included with purchased goods before the onset of the internet were typically toys, stickers, puzzles, or physical games, whereas they are now mostly songs, videos, digital games, or free applications which generally include either the company’s branding mascot or the cross-promotion character they are using at the time. As a child, I remember that getting free gifts was a huge incentive for me to ask my parents for something at the store, and can vouch for how strong of an effect this can have on a kid’s mind.

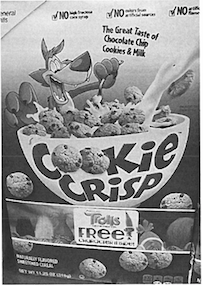

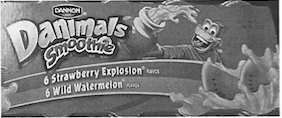

Not all tactics to gain consumer interests are as noticeable though, yet still appear to have positive effects on children. Bright colors, boldness of design, cartoon mascots, and catch phrases are all part of the overall enjoyable experience that corporations try to create for young customers. The location of the product on the shelves is also important. Most children’s products are kept on bottom shelves, especially in aisles of grocery stores where adult and child products are mixed. This way the items are in their direct line of sight and reach, creating a higher probability for purchase. Another method that is not so heavily researched, but is extremely convincing, comes from “Eyes in the Aisles: Why is Cap’n Crunch Looking Down at My Child?”, an article by Aviva Musicus and other scholars. This article breaks down the research study of whether eye contact with cartoon characters on cereal products creates a sense of comfort and trust, and if it affects the item’s purchase. Many cereal characters’ eyes look down (as shown), typically looking at the product that pictured on the box—but also at the smaller people perusing the aisles, like children. Researchers wanted to determine if this tactic is intentional, and if so, if it is effective in selling more product. This tactic appears to be used mostly for cereal, but I was able to find similar artistry on Danimals yogurt drinks and some fruit snacks as well. It was concluded through the study that eye-contact by a friendly face in general creates feelings of trust and friendship. In applying this to product branding, the study confirmed with many of its subjects, that a welcoming glance for a child can essentially create positive feelings that make him or her feel more connected to the product and in turn choose it over others. The findings of the study for whether or not characters are designed to make eye contact were inconclusive, however (Musicus et al. 716-724).

Not all tactics to gain consumer interests are as noticeable though, yet still appear to have positive effects on children. Bright colors, boldness of design, cartoon mascots, and catch phrases are all part of the overall enjoyable experience that corporations try to create for young customers. The location of the product on the shelves is also important. Most children’s products are kept on bottom shelves, especially in aisles of grocery stores where adult and child products are mixed. This way the items are in their direct line of sight and reach, creating a higher probability for purchase. Another method that is not so heavily researched, but is extremely convincing, comes from “Eyes in the Aisles: Why is Cap’n Crunch Looking Down at My Child?”, an article by Aviva Musicus and other scholars. This article breaks down the research study of whether eye contact with cartoon characters on cereal products creates a sense of comfort and trust, and if it affects the item’s purchase. Many cereal characters’ eyes look down (as shown), typically looking at the product that pictured on the box—but also at the smaller people perusing the aisles, like children. Researchers wanted to determine if this tactic is intentional, and if so, if it is effective in selling more product. This tactic appears to be used mostly for cereal, but I was able to find similar artistry on Danimals yogurt drinks and some fruit snacks as well. It was concluded through the study that eye-contact by a friendly face in general creates feelings of trust and friendship. In applying this to product branding, the study confirmed with many of its subjects, that a welcoming glance for a child can essentially create positive feelings that make him or her feel more connected to the product and in turn choose it over others. The findings of the study for whether or not characters are designed to make eye contact were inconclusive, however (Musicus et al. 716-724).

While the amount of money that is spent on food advertising for children seems exorbitant to most, it is not necessarily the amount of money or the advertising in itself that is the problem for many Americans; instead, it is the type of food that is being promoted with such a heavy hand. Soda, fruit snacks, donuts, cereal, granola bars, Pop-Tarts, frozen meals, sugary yogurts, cookies, snack cakes, ice cream, and popsicles are some of the most branded items for children at grocery stores. Most of the things listed are not adequate snacks or meals, and yet it is proven that children want them the most due to their appealing containers. Depending on the age of the child, they may not even know what the product is but still want it, because of the color of the package or because their favorite character is on it. Experts agree that the majority of the highly advertised and branded food products are unhealthy and that they can contribute to higher weights if consumed in too large of quantities or too often. One such expert is Kathleen Keller, along with her research partners from various universities in the United States. They have found that the most marketed food items at the grocery store are generally high in fat, sodium, and sugar, which is easily confirmed with a look in your city’s popular supermarkets. Keller also determined that children who are enticed by “good” marketing and branding for unhealthy products often keep going back for more due to the addictive nature of those three main ingredients (409).

While the amount of money that is spent on food advertising for children seems exorbitant to most, it is not necessarily the amount of money or the advertising in itself that is the problem for many Americans; instead, it is the type of food that is being promoted with such a heavy hand. Soda, fruit snacks, donuts, cereal, granola bars, Pop-Tarts, frozen meals, sugary yogurts, cookies, snack cakes, ice cream, and popsicles are some of the most branded items for children at grocery stores. Most of the things listed are not adequate snacks or meals, and yet it is proven that children want them the most due to their appealing containers. Depending on the age of the child, they may not even know what the product is but still want it, because of the color of the package or because their favorite character is on it. Experts agree that the majority of the highly advertised and branded food products are unhealthy and that they can contribute to higher weights if consumed in too large of quantities or too often. One such expert is Kathleen Keller, along with her research partners from various universities in the United States. They have found that the most marketed food items at the grocery store are generally high in fat, sodium, and sugar, which is easily confirmed with a look in your city’s popular supermarkets. Keller also determined that children who are enticed by “good” marketing and branding for unhealthy products often keep going back for more due to the addictive nature of those three main ingredients (409).

Keller and her team also conducted three different experiments, two of which I will discuss. It is important to add that Keller is not the only one that has conducted these studies, but is being used as an example of the type of tests that have been executed in regards to branding, and the movements that have been made in the scientific field to try to help with the obesity epidemic. In the first study, Keller sought to determine whether actively watching commercials made young people eat more. She found that all of the children, regardless of age and weight, ate more food while watching advertisements about food than when they were not. Others researchers however, have had opposing viewpoints based on their collected data in similar studies, and the issue is that there are too many variables with this type of test. Age, type of food offered, advertisements watched, familiarity with the ads or characters used, and other factors all come into play and can skew the data. Some studies found that none of the children ate more while watching television advertisements about food, while others concluded that despite some children eating more, not all of them did like in Keller’s experiment. The issue with the variables are still being worked out in order to have more accurate data (Keller 380-381).

In the second trial, one test group was offered raw fruits and vegetables in containers with characters on the outside, such as Elmo, and included a sticker inside like many of the products that come with free gifts. Both groups consisted of children of different ages that regularly ate below the recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables, which is one to three cups a day depending on age. The kids who had containers with the characters increased their consumption of fruits and vegetables by approximately three servings from where they were before the test started, while the intake for the second group with the plain containers did not go up at all.

The most interesting part of the study is that when the experiment was over the children who were in the character test group continued on eating more fruits and vegetables despite the fact that they no longer had the original containers. This could potentially mean that once a child makes a connection with a product, that it becomes engrained in their minds and that they no longer need stickers, toys, or package designs in order to appreciate or crave a certain food. However, more testing would have to be done to confirm this (Keller 383-384). While this could be a negative thing in the context of unhealthy food product advertising, it also shows that cross-branding could be used to promote healthier alternatives. Keller’s results along with the responses of the scientists that conducted like-studies, appear to have a general consensus that while there is correlational data between advertising, branding, and obesity, it is not a direct one, which is encouraging (Breiner 5). Advertising itself does not increase obesity, but rather the products being advertised and the methods by which they are advertised.

The good news is that since advertising and branding does not have a straight link to obesity then it should be possible to prevent some occurrences from happening, either from the government and food companies themselves, or from inside the home. On the governmental side, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) continue to partner up with each other, along with the leading food manufacturers, to discuss ways that companies can promote healthier eating. Some companies have already joined the fight by offering lower calorie, sugar, fat, or sodium versions of their popular foods by using whole grains or by limiting portion sizes (Wilks 66).

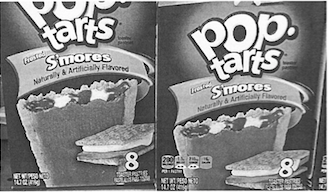

Another example of governmental efforts was in 2010, when Michelle Obama launched the campaign for “Facts Up Front” with the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA). The goal of this movement was to encourage food distributors to voluntarily put nutrition information on the front of the package. The act is to encourage label reading and awareness of what is being consumed, with labels being monitored by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to ensure that customers get accurate information (“Facts”). There are still many companies, however, that do not state their health facts on the front of the container though, and the FTC, HHS, and GMA are always pushing for more  participation. As you can see in the picture I took at Fred Meyer’s, even companies that have sought action can have the same product with and without nutrition labeling sitting right next to each other on the shelves. In the photo, the nutrition label is on the bottom left of the package of Pop-Tarts in the right-hand photo, but is absent from the one on the left. It seems like this could occur if a company either began or stopped their contribution to the “Facts Up Front” movement and older stock was being sold alongside newer stock. It is possible as well that there could be inconsistent procedures in the company with packaging; however, this seems unlikely since companies would have to set up their machines to create varying products. Hopefully, as more years pass, front-labeling will become the overall standard in the marketplace.

participation. As you can see in the picture I took at Fred Meyer’s, even companies that have sought action can have the same product with and without nutrition labeling sitting right next to each other on the shelves. In the photo, the nutrition label is on the bottom left of the package of Pop-Tarts in the right-hand photo, but is absent from the one on the left. It seems like this could occur if a company either began or stopped their contribution to the “Facts Up Front” movement and older stock was being sold alongside newer stock. It is possible as well that there could be inconsistent procedures in the company with packaging; however, this seems unlikely since companies would have to set up their machines to create varying products. Hopefully, as more years pass, front-labeling will become the overall standard in the marketplace.

Another governmental organization that joined in the battle against obesity is the Institute of Medicine (IOM) at the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). While the IOM does not have any direct say on what types of policies are enacted, they do conduct studies on childhood obesity and ways to prevent it, including advertising’s effects on eating patterns and weight. After they summarize their findings, they submit the information in a report to agencies like the FDA to see if they can encourage any change. In their report from 2009, they witnessed a correlation between advertising and early weight gain and acknowledged that advertising practices are not in line with healthy eating. The IOM states that food manufacturers should be more aware of what types of foods that they are advertising

to children and adolescents. They do also recognize the groups that are working to make a change, like the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation (which works with the food industry to try to lower caloric content of current food products), as well as the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (a non-profit that encourages advertising for nutritionally dense foods only and inspires healthy eating habits within households) (Breiner 6-9). Examples of productive advertising could be using characters on packages of carrots, apples, milk, or any other healthy items, commercials that promote health and wellness for kids, and games or applications that are directed to teach kids about nutrition. However, many experts believe that any type of advertising and branding, even if it is to influence positive food choices, becomes negative as it continues to endorse a society based on consumerism. This is just a broad overview of what type of work is being done and what major players are involved, but because of the severity of the obesity epidemic, there is much more work going on behind the scenes than what is listed here.

The government is not the only entity that can make a change, however, and modifications can possibly be made inside the home to avoid excessive marketing control on young ones and their consumption of unhealthy food products. It is important to say, though, that not everyone may be able to make certain positive changes; those who can are encouraged to do so. As stated previously, there are many factors that go into children’s eating habits. Some of the most common reasons are that unhealthier items are less expensive, and that fresh food goes bad faster, so purchasing nutritional options may not be possible for lower-income families. There is also the issue of research and education: some parents or guardians may not be well-informed of advertising’s effects on younger minds or how to serve well-rounded meals, and they may also not have a lot of access to resources that could help. It is unwise to say that all people in the United States have access to the same information, as this is just not the case.

But families that do have the means to purchase healthier products and are knowledgeable on the subjects of advertising and nutrition (or have ways learn about these subjects) are greatly encouraged to take small or big steps to implementing change at home. Some steps could be to limit time spent on mobile devices, so that kids and teens are not viewing as many advertisements each day, or to completely eliminate television viewing and the use of internet-based devices if a more extreme option was needed or wanted. If the cost of groceries is not a major issue, then encouraging the consumption of new fruits and vegetables each week is an easy place to start, as well as offering more lean proteins, healthy fats like olive oil and coconut oil, and less processed starches. Probably the most crucial element is to talk to kids about consumerism: how to be a smart and mindful customer, and how to not let advertisements influence our decision-making. They can also make a point to discuss portion control, and what healthy eating means for our bodies and our longevity of life. Since children develop preferences as early as two years old, it is best to start implementing healthier eating habits and interactive conversations as early as possible—but it is never too late to start.

It is encouraging to know that companies are making changes to their policies and product ingredients, and that governmental organizations, non-profits, and families continue to strive for a healthier country. There should be better protection of our youth, but what is hindering a more drastic movement for change of advertising techniques targeted to children and adolescents is the amount of variables in studies due to age, weight, background, mental health and capacity, etc. Because of these differences amongst children, studies are not consistent, which creates feeble evidence for marketing and branding’s effects on childhood obesity. But there is still hope for the future of our country, as scientists continue to strive to establish better research techniques that can either solidly prove or deny the correlation between the two. In the meantime, households at the least can start having conversations with their children and teenagers about marketing’s effect on their preferences and choices, and can proactively work on breaking the hold that food corporations have over so many of them.

Works Cited

Aaker, David. “Brand Personalities Are Like Snowflakes.” Marketing News, vol. 49, no. 7, 1 July 2015, pp. 20-21. EBSCOhost, http://web.a.ebscohost.com.proxy.lib.pdx.edu/ehost/c8@sessionmgr.

Breiner, Heather, et al. Challenges and Opportunities for Change in Food Marketing to Children and Youth Workshop Summary. National Academies Press, May 2013. ProQuest eBook Library, http://site.ebrary.com/lib/portlandstate/reader.action?docID=10863889.

“Childhood Obesity Facts: Prevalence of Childhood Obesity in the United States, 2011-2014.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html.

“Facts Up Front Front-of-Pack Labeling Initiative.” Grocery Manufacturers Association, 2016, http://www.gmaonline.org/issues-policy/health-nutrition/facts-up-front-front-of-pack-labeling-initiative.

“FTC Releases Follow-Up Study Detailing Promotional Activities, Expenditures, and Nutritional Profiles of Food Marketed to Children and Adolescents: Commends Industry for Progress, Urges Broader Participation and Continued Improvement.” Federal Trade Commission, 21 December 2012, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2012/12/ftc-releases-follow-study-detailing-promotional-activities.

Harris, Jennifer L., et al. “Marketing Foods to Children and Adolescents: Licensed Characters and Other Promotions on Packaged Foods in the Supermarket.” The Nutrition Society, vol. 13, no. 3, March 2010, pp. 409-417. Cambridge University Press, doi: 10.1017/S1368980009991339.

Keller, Kathleen L., et al. “The Impact of Food Branding on Children’s Eating Behavior and Obesity.” Physiology and Behavior, vol. 106, no. 3, 6 June 2012, pp. 379-386. Elsevier ScienceDirect, doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.03.011.

McGinnis, J. Michael and Jennifer Appleton Gootman. Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity? National Academies Press, April 2006. ProQuest eBook Library, http://site.ebrary.com/lib/portlandstate/detail.action?docID=10120677.

Musicus, Avira, et al. “Eyes in the Aisles: Why is Cap’n Crunch Looking Down at My Child?” Environment and Behavior, vol. 47, no. 7, 2015, pp. 715-733. SAGE, http://eab.sagepub.com.proxy.lib.pdx.edu/content/47/7/715.full.pdf html.

“Should Advertising to Kids Be Banned?” Stuff You Should Know, HowStuffWorks, 24 Nov 2016, http://www.stuffyoushouldknow.com/podcasts/banned-kids-advertising.htm.

Wilks, Nicoletta A. Marketing Food to Children and Adolescents. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2009. ProQuest eBook Library, http://site.ebrary.com/lib/portlandstate/reader.action?doc1D=10671274.

Teacher Takeaways “I like how this essay combines extensive research with the author’s own direct observations. Together, these strategies can produce strong logos and ethos appeals, respectively. However, the author too often wants the information speak for itself, and because the findings of many of the studies were inconclusive or contradictory, they don’t support the author’s central claim. These studies certainly could still be used effectively, but this essay demonstrates the importance of actively engaging in argument—the author cannot just present the information, but needs to interpret it for the audience to demonstrate how the evidence supports the thesis.”– Professor Dunham

- Essay by Jessica Beer, Portland State University, 2016. Reproduced with permission from the student author. ↵