Chapter 7: Argumentation

To a nonconfrontational person (like me), argument is a dirty word. It surfaces connotations of raised voices, slammed doors, and dominance; it arouses feelings of anxiety and frustration.

But argument is not inherently bad. In fact, as a number of great thinkers have described, conflict is necessary for growth, progress, and community cohesion. Through disagreement, we challenge our commonsense assumptions and seek compromise. The negative connotations surrounding ‘argument’ actually point to a failure in the way that we argue.

Check out this video on empathy: it provides some useful insight to the sort of listening, thinking, and discussion required for productive arguments.

Now, spend a few minutes reflecting on the last time you had an argument with a loved one. What was it about? What was it really about? What made it difficult? What made it easy?

Often, arguments hinge on the relationship between the arguers: whether written or verbal, that argument will rely on the specific language, approach, and evidence that each party deems valid. For that reason, the most important element of the rhetorical situation is audience. Making an honest, impactful, and reasonable connection with that audience is the first step to arguing better.

Unlike the argument with your loved one, it is likely that your essay will be establishing a brand-new relationship with your reader, one which is untouched by your personal history, unspoken bonds, or other assumptions about your intent. This clean slate is a double-edged sword: although you’ll have a fresh start, you must more deliberately anticipate and navigate your assumptions about the audience. What can you assume your reader already knows and believes? What kind of ideas will they be most swayed by? What life experiences have they had that inform their worldview?

This chapter will focus on how the answers to these questions can be harnessed for productive, civil, and effective arguing. Although a descriptive personal narrative (Section 1) and a text wrestling analysis (Section 2) require attention to your subject, occasion, audience, and purpose, an argumentative essay is the most sensitive to rhetorical situation of the genres covered in this book. As you complete this unit, remember that you are practicing the skills necessary to navigating a variety of rhetorical situations: thinking about effective argument will help you think about other kinds of effective communication.

| argument | a rhetorical mode in which different perspectives on a common issue are negotiated. See Aristotelian and Rogerian arguments. |

| Aristotelian argument | a mode of argument by which a writer attempts to convince their audience that one perspective is accurate. |

| audience | the intended consumers for a piece of rhetoric. Every text has at least one audience; sometimes, that audience is directly addressed, and other times we have to infer. |

| call-to-action | a persuasive writer’s directive to their audience; usually located toward the end of a text. Compare with purpose. |

| ethos | a rhetorical appeal based on authority, credibility, or expertise. |

| kairos | the setting (time and place) or atmosphere in which an argument is actionable or ideal. Consider alongside “occasion.” |

| logical fallacy | a line of logical reasoning which follows a pattern of that makes an error in its basic structure. For example, Kanye West is on TV; Animal Planet is on TV. Therefore, Kanye West is on Animal Planet. |

| logos | a rhetorical appeal to logical reasoning. |

| multipartial | a neologism from ‘impartial,’ refers to occupying and appreciating a variety of perspectives rather than pretending to have no perspective. Rather than unbiased or neutral, multipartial writers are balanced, acknowledging and respecting many different ideas. |

|

pathos |

a rhetorical appeal to emotion. |

|

rhetorical appeal |

a means by which a writer or speaker connects with their audience to achieve their purpose. Most commonly refers to logos, pathos, and ethos. |

|

Rogerian argument |

a mode of argument by which an author seeks compromise by bringing different perspectives on an issue into conversation. Acknowledges that no one perspective is absolutely and exclusively ‘right’; values disagreement in order to make moral, political, and practical decisions. |

|

syllogism |

a line of logical reasoning similar to the transitive property (If a=b and b=c, then a=c). For example, All humans need oxygen; Kanye West is a human. Therefore, Kanye West needs oxygen. |

Techniques

“But I Just Want to Write an Unbiased Essay”

Let’s begin by addressing a common concern my students raise when writing about controversial issues: neutrality. It’s quite likely that you’ve been trained, at some point in your writing career, to avoid bias, to be objective, to be impartial. However, this is a habit you need to unlearn, because every text is biased by virtue of being rhetorical. All rhetoric has a purpose, whether declared or secret, and therefore is partial.

“Honest disagreement is often a good sign of progress.” – Mahatma Gandhi

Instead of being impartial, I encourage you to be multipartial. In other words, you should aim to inhabit many different positions in your argument—not zero, not one, but many. This is an important distinction: no longer is your goal to be unbiased; rather, it is to be balanced. You will not provide your audience a neutral perspective, but rather a perspective conscientious of the many other perspectives out there.

Common Forms of Argumentation

In the study of argumentation, scholars and authors have developed a great variety of approaches: when it comes to convincing, there are many different paths that lead to our destination. For the sake of succinctness, we will focus on two: the Aristotelian argument and the Rogerian Argument.[1] While these two are not opposites, they are built on different values. Each will employ rhetorical appeals like those discussed later, but their purposes and guiding beliefs are different.

Aristotelian Argument

In Ancient Greece, debate was a cornerstone of social life. Intellectuals and philosophers devoted hours upon hours of each day to honing their argumentative skills. For one group of thinkers, the Sophists, the focus of argumentation was to find a distinctly “right” or “wrong” position. The more convincing argument was the right one: the content mattered less than the technique by which it was delivered.

In turn, the purpose of an Aristotelian argument is to persuade someone (the other debater and/or the audience) that the speaker was correct. Aristotelian arguments are designed to bring the audience from one point of view to the other.

There will be tension between a point and counterpoint (or, to borrow a term from German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte, “thesis” and “antithesis.”) These two viewpoints move in two opposite directions, almost like a tug-of-war.

Therefore, an Aristotelian arguer tries to demonstrate the validity of their direction while addressing counterarguments: “Here’s what I believe and why I’m right; here’s what you believe and why it’s wrong.” The author seeks to persuade their audience through the sheer virtue of their truth.

You can see Aristotelian argumentation applied in “We Don’t Care about Child Slaves.”

Rogerian Argument

In contrast, Rogerian arguments are more invested in compromise. Based on the work of psychologist Carl Rogers, Rogerian arguments are designed to enhance the connection between both sides of an issue. This kind of argument acknowledges the value of disagreement in material communities to make moral, political, and practical decisions.

Often, a Rogerian argument will begin with a fair statement of someone else’s position and consideration of how that could be true. In other words, a Rogerian arguer addresses their ‘opponent’ more like a teammate: “What you think is not unreasonable; I disagree, but I can see how you’re thinking, and I appreciate it.” Notice that by taking the other ideas on their own terms, you demonstrate respect and cultivate trust and listening.

The thesis is an intellectual proposition.The antithesis is a critical perspective on the thesis.The synthesis solves the conflict between the thesis and antithesis by reconciling their common truths and forming a new proposition.

The rhetorical purpose of a Rogerian argument, then, is to come to a conclusion by negotiating common ground between moral-intellectual differences. Instead of debunking an opponent’s counterargument entirely, a Rogerian arguer would say, “Here’s what each of us thinks, and here’s what we have in common. How can we proceed forward to honor our shared beliefs but find a new, informed position?” In Fichte’s model of thesis-antithesis-synthesis,[2] both debaters would pursue synthesis. The author seeks to persuade their audience by showing them respect, demonstrating a willingness to compromise, and championing the validity of their truth as one among other valid truths.

You can see Rogerian argumentation applied in “Vaccines: Controversies and Miracles.”

| Position | Position | Rogerian |

| Wool sweaters are the best clothing for cold weather. | Wool sweaters are the best clothing for cold weather because they are fashionable and comfortable. Some people might think that wool sweaters are itchy, but those claims are ill-informed. Wool sweaters can be silky smooth if properly handled in the laundry. | Some people might think that wool sweaters are itchy, which can certainly be the case. I’ve worn plenty of itchy wool sweaters. But wool sweaters can be silky smooth if properly handled in the laundry; therefore, they are the best clothing for cold weather. If you want to be cozy and in-style, consider my laundry techniques and a fuzzy wool sweater. |

Before moving on, try to identify one rhetorical situation in which Aristotelian argumentation would be most effective, and one in which Rogerian argumentation would be preferable. Neither form is necessarily better, but rather both are useful in specific contexts. In what situations might you favor one approach over another?

Rhetorical Appeals

Regardless of the style of argument you use, you will need to consider the ways you engage your audience. Aristotle identified three kinds of rhetorical appeals: logos, pathos, and ethos. Some instructors refer to this trio as the “rhetorical triangle,” though I prefer to think of them as a three-part Venn diagram.[3] The best argumentation engages all three of these appeals, falling in the center where all three overlap. Unbalanced application of rhetorical appeals is likely to leave your audience suspicious, doubtful, or even bored.

Logos

You may have inferred already, but logos refers to an appeal to an audience’s logical reasoning. Logos will often employ statistics, data, or other quantitative facts to demonstrate the validity of an argument. For example, an argument about the wage

gap might indicate that women, on average, earn only 80 percent of the salary that men in comparable positions earn; this would imply a logical conclusion that our economy favors men.

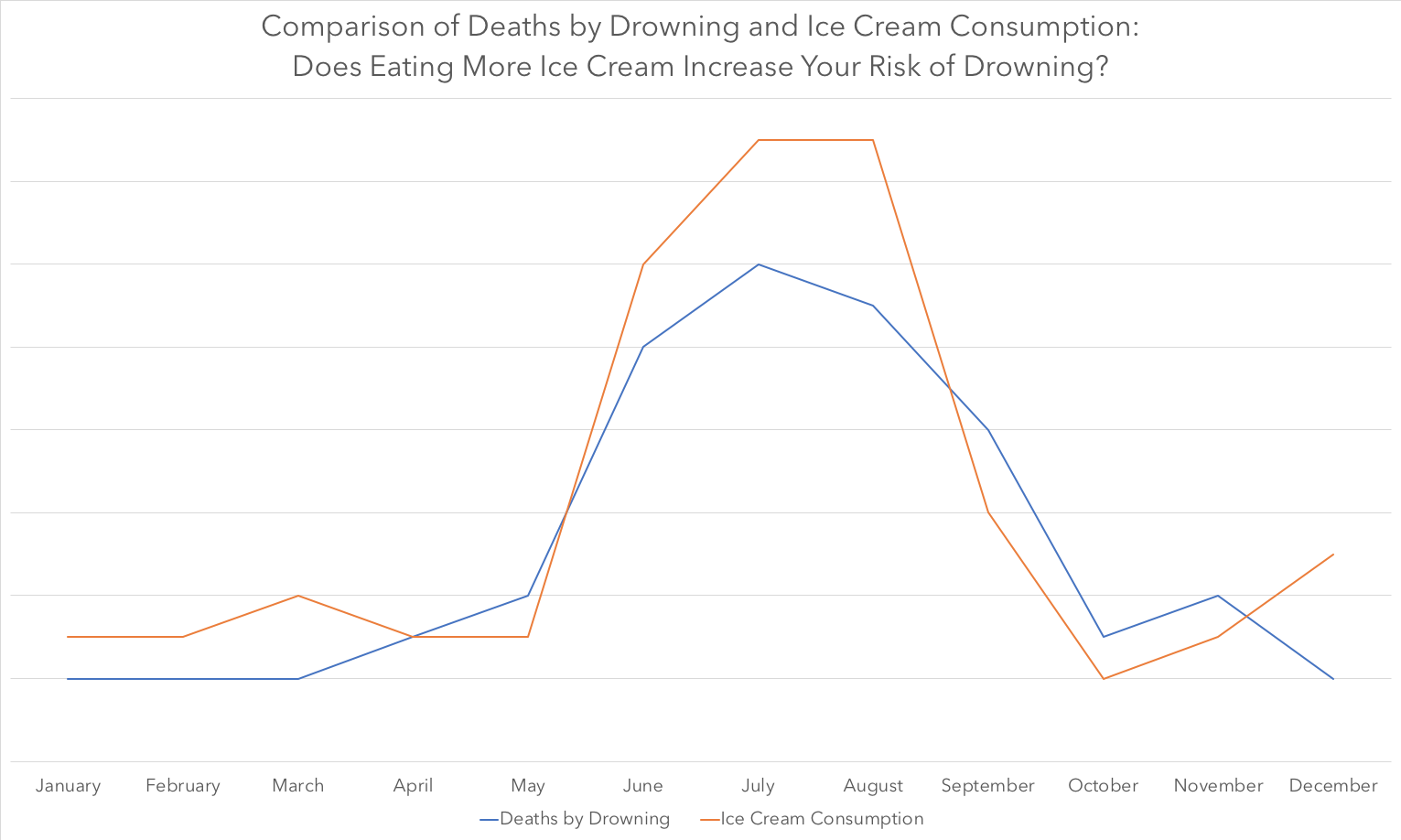

However, stating a fact or statistic does not alone constitute logos. For instance, when I show you this graph[4], I am not yet making a logical appeal:

Yes, the graph is “fact-based,” drawing on data to illustrate a phenomenon. That characteristic alone, though, doesn’t make a logical appeal. For my appeal to be logical, I also need to interpret the graph:

As is illustrated here, there is a direct positive correlation between ice cream consumption and deaths by drowning: when people eat more ice cream, more people drown. Therefore, we need to be more careful about waiting 30 minutes after we eat ice cream.

Of course, this conclusion is inaccurate; it is a logical fallacy described in the table below called “post hoc, ergo propter hoc.” However, the example illustrates that your logic is only complete when you’ve drawn a logical conclusion from your facts, statistics, or other information.

There are many other ways we draw logical conclusions. There are entire branches of academia dedicated to understanding the many kinds of logical reasoning, but we might get a better idea by looking at a specific kind of logic. Let’s take for example the logical syllogism, which might look something like this:

- All humans require oxygen.

- Kanye West is a human.

- Therefore, Kanye West requires oxygen.

Pretty straightforward, right? We can see how a general rule (major premise) is applied to a specific situation (minor premise) to develop a logical conclusion. I like to introduce this kind of logic because students sometimes jump straight from the major premise to the conclusion; if you skip the middle step, your logic will be less convincing.

It does get a little more complex. Consider this false syllogism: it follows the same structure (general rule specific situation), but it reaches an unlikely conclusion.

- All penguins are black and white.

- My television is black and white.

- Therefore, my television is a penguin.

This is called a logical fallacy. Logical fallacies are part of our daily lives. Stereotypes, generalizations, and misguided assumptions are fallacies you’ve likely encountered. You may have heard some terms about fallacies already: red herring, slippery slope, non sequitur. Fallacies follow patterns of reasoning that would otherwise be perfectly acceptable to us, but within their basic structure, they make a mistake. Aristotle identified that fallacies happen on the “material” level (the content is fallacious—something about the ideas or premises is flawed) and the “verbal” level (the writing or speech is fallacious—something about the delivery or medium is flawed).

It’s important to be able to recognize these so that you can critically interrogate others’ arguments and improve your own. Here are some of the most common logical fallacies:

| Fallacy | Description | Example |

| Post hoc, ergo propter hoc | “After this, therefore because of this” – a confusion of cause-and-effect with coincidence, attributing a consequence to an unrelated event. This error assumes that correlation equals causation, which is sometimes not the case. | Statistics show that rates of ice cream consumption and deaths by drowning both increased in June. This must mean that ice cream causes drowning. |

| Non sequitur | “Does not follow” – a random digression that distracts from the train of logic (like a “red herring”), or draws an unrelated logical conclusion. John Oliver calls one manifestation of this fallacy “whataboutism,” which he describes as a way to deflect attention from the subject at hand. |

Sherlock is great at solving crimes; therefore, he’ll also make a great father. Sherlock Holmes smokes a pipe, which is unhealthy. But what about Bill Clinton? He eats McDonald’s every day, which is also unhealthy. |

| Straw Man | An oversimplification or cherry-picking of the opposition’s argument to make them easier to attack. | People who oppose the destruction of Confederate monuments are all white supremacists. |

| Ad hominem | “To the person” – a personal attack on the arguer, rather than a critique of their ideas. | I don’t trust Moriarty’s opinion on urban planning because he wears bowties. |

| Slippery Slope | An unreasonable prediction that one event will lead to a related but unlikely series of events that follows. | If we let people of the same sex get married, then people will start marrying their dogs too! |

| False Dichotomy | A simplification of a complex issue into only two sides. | Given the choice between pizza and Chinese food for dinner, we simply must choose Chinese. |

| Learn about other logical fallacies in the Additional Recommended Resources appendix. |

Pathos

The second rhetorical appeal we’ll consider here is perhaps the most common: pathos refers to the process of engaging the reader’s emotions. (You might recognize the Greek root pathos in “sympathy,” “empathy,” and “pathetic.”) A writer can evoke a great variety of emotions to support their argument, from fear, passion, and joy to pity, kinship, and rage. By playing on the audience’s feelings, writers can increase the impact of their arguments.

There are two especially effective techniques for cultivating pathos that I share with my students:

- Make the audience aware of the issue’s relevance to them specifically—“How would you feel if this happened to you? What are we to do about this issue?”

- Tell stories. A story about one person or one community can have a deeper impact than broad, impersonal data or abstract, hypothetical statements. Consider the difference between

About 1.5 million pets are euthanized each year

and

Scooter, an energetic and loving former service dog with curly brown hair like a Brillo pad, was put down yesterday.

- Both are impactful, but the latter is more memorable and more specific.

Pathos is ubiquitous in our current journalistic practices because people are more likely to act (or, at least, consume media) when they feel emotionally moved.[5] Consider, as an example, the outpouring of support for detained immigrants in June 2018, reacting to the Trump administration’s controversial family separation policy. As stories and images like this one surfaced, millions of dollars were raised in a matter of days on the premise of pathos, and resulted in the temporary suspension of that policy.

Ethos

Your argument wouldn’t be complete without an appeal to ethos. Cultivating ethos refers to the means by which you demonstrate your authority or expertise on a topic. You’ll have to show your audience that you’re trustworthy if they are going to buy your argument.

There are a handful of ways to demonstrate ethos:

- By personal experience: Although your lived experience might not set hard-and-fast rules about the world, it is worth noting that you may be an expert on certain facets of your life. For instance, a student who has played rugby for fifteen years of their life is in many ways an authority on the sport.

- By education or other certifications: Professional achievements demonstrate ethos by revealing status in a certain field or discipline.

- By citing other experts: The common expression is “Stand on the shoulders of giants.” You can develop ethos by pointing to other people with authority and saying, “Look, this smart/experienced/qualified/important person agrees with me.”

A common misconception is that ethos corresponds with “ethics.” However, you can remember that ethos is about credibility because it shares a root with “authority.”

Sociohistorical Context of Argumentation

This textbook has emphasized consideration of your rhetorical occasion, but it bears repeating here that “good” argumentation depends largely on your place in time, space, and culture. Different cultures throughout the world value the elements of argumentation differently, and argument has different purposes in different contexts. The content of your argument and your strategies for delivering it will change in every unique rhetorical situation.

Continuing from logos, pathos, and ethos, the notion of kairos speaks to this concern. To put it in plain language, kairos is the force that determines what will be the best argumentative approach in the moment in which you’re arguing; it is closely aligned with rhetorical occasion. According to rhetoricians, the characteristics of the kairos determine the balance and application of logos, pathos, and ethos.

Moreover, your sociohistorical context will bear on what you can assume of your audience. What can you take for granted that your audience knows and believes? The “common sense” that your audience relies on is always changing: common sense in the U.S. in 1950 was much different from common sense in the U.S. in 1920 or common sense in the U.S. in 2018. You can make assumptions about your audience’s interests, values, and background knowledge, but only with careful consideration of the time and place in which you are arguing.

As an example, let’s consider the principle of logical noncontradiction. Put simply, this means that for an argument to be valid, its logical premises must not contradict one another: if A = B, then B = A. If I said that a dog is a mammal and a mammal is an animal, but a dog is not an animal, I would be contradicting myself. Or, “No one drives on I-84; there’s too much traffic.” This statement contradicts itself, which makes it humorous to us.

However, this principle of non-contradiction is not universal. Our understanding of cause and effect and logical consistency is defined by the millennia of knowledge that has been produced before us, and some cultures value the contradiction rather than perceive it as invalid.[6] This is not to say that either way of seeing the world is more or less accurate, but rather to emphasize that your methods of argumentation depend tremendously on sociohistorical context.

Activities

Op-Ed Rhetorical Analysis

One form of direct argumentation that is readily available is the opinion editorial, or op-ed. Most news sources, from local to international, include an opinion section. Sometimes, these pieces are written by members of the news staff; sometimes, they’re by contributors or community members. Op-eds can be long (e.g., comprehensive journalistic articles, like Ta-Nehisi Coates’ landmark “The Case for Reparations”) or they could be brief (e.g., a brief statement of one’s viewpoint, like in your local newspaper’s Letter to the Editor section).

To get a better idea of how authors incorporate rhetorical appeals, complete the following rhetorical analysis exercise on an op-ed of your choosing.

- Find an op-ed (opinion piece, editorial, or letter to the editor) from either a local newspaper, a national news source, or an international news corporation. Choose something that interests you, since you’ll have to read it a few times over.

- Read the op-ed through once, annotating parts that are particularly convincing, points that seem unsubstantiated, or other eye-catching details.

- Briefly (in one to two sentences) identify the rhetorical situation (SOAP) of the op-ed.

- Write a citation for the op-ed in an appropriate format.

- Analyze the application of rhetoric.

- Summarize the issue at stake and the author’s position.

- Find a quote that represents an instance of logos.

- Find a quote that represents an instance of pathos.

- Find a quote that represents an instance of ethos.

- Paraphrase the author’s call-to-action (the action or actions the author wants the audience to take). A call-to-action will often be related to an author’s rhetorical purpose.

- In a one-paragraph response, consider: Is this rhetoric effective? Does it fulfill its purpose? Why or why not?

VICE News Rhetorical Appeal Analysis

VICE News, an alternative investigatory news outlet, has recently gained acclaim for its inquiry-driven reporting on current issues and popular appeal, much of which is derived from effective application of rhetorical appeals.

You can complete the following activity using any of their texts, but I recommend “State of Surveillance” from June 8, 2016. Take notes while you watch and complete the organizer after you finish.

- What is the title and publication date of the text?

- Briefly summarize the subject of this text.

- How would you describe the purpose of this text?

- Pathos

- Provide at least 3 examples of pathos that you observed in the text:

- How would you describe the overall tone of the piece? What mood does it evoke for the viewer/reader?

- Logos

- Provide at least 3 examples of logos that you observed in the text:

- In addition to presenting data and statistics, how does the text logically interpret evidence?

- Ethos

- Provide at least 3 examples of ethos that you observed in the text:

- How might one person, idea, or source both enhance and detract from the cultivation of ethos? (Consider Edward Snowden in “State of Surveillance,” for instance.)

Audience Analysis: Tailoring Your Appeals

Now that you’ve observed the end result of rhetorical appeals, let’s consider how you might tailor your own rhetorical appeals based on your audience.

First, come up with a claim that you might try to persuade an audience to believe. Then, consider how you might develop this claim based on the potential audiences listed in the organizer on the following pages. An example is provided after the empty organizer if you get stuck.

Claim:

Audience #1: Business owners. What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe?

- Logos

- Pathos

- Ethos

Audience #2: Local political officials. What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe?

- Logos

- Pathos

- Ethos

Audience #3: One of your family members. What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe?

- Logos

- Pathos

- Ethos

- Audience #4: Invent your own. What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe?

- Logos

- Pathos

- Ethos

Model

Claim: Employers should offer employees discounted or free public transit passes.

Audience #1: Business owners. What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe?

- Logos: They are concerned with profit margins – I need to show that this will benefit them financially: “If employees are able to access transportation more reliably, then they are more likely to arrive on time, which increases efficiency.”

- Pathos: They are concerned with employee morale – I need to show that access will improve employee satisfaction: “Every employer wants their employees to feel welcome at the office. Does your work family dread the start of the day?”

- Ethos: They are more likely to believe my claim if other business owners, the chamber of commerce, etc., back it up: “In 2010, Portland employer X started providing free bus passes, and their employee retention rate has increased 30%.”

Audience #2: Local political officials. What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe?

- Logos: They are held up by political bureaucracy – I need to show a clear, direct path to executing my claim: “The implementation of such a program could be modeled after an existing system, like EBT cards.”

- Pathos: They are concerned with reelection – I need to show that this will build an enthusiastic voter base: “When politicians show concern for workers, their approval rates increase. If the voters are happy, you’ll be happy!”

- Ethos: They are more likely to believe my claim if I show other cities and their political officials executing a similar plan – I could also draw on my own experiences because I am a member of the community they represent: “As an employee who uses public transit (and an enthusiastic voter), I can say that I would make good use of this benefit.”

Audience #3: One of your family members. What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe?

- Logos: My mom has to drive all over the state for her job – I could explain how this will benefit her: “If you had a free or discounted pass, you could drive less. Less time behind the wheel means a reduction of risk!”

- Pathos: My mom has to drive all over the state for her job – I could tap into her frustration: “Aren’t you sick of a long commute bookending each day of work? The burning red glow of brakelights and the screech of tires—it doesn’t have to be this way.”

- Ethos: My mom might take my word for it since she trusts me already: “Would I mislead you? I hate to say I told you so, but I was totally right about the wool sweater thing.”

Audience #4: Car Drivers. What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe?

- Logos: They are concerned with car-related expenses – I need to lay out evidence of savings from public transit: “Have you realized that taking the bus two days a week could save you $120 in gas per month?”

- Pathos: They are frustrated by traffic, parking, etc. – I could play to that emotion: “Is that a spot? No. Is that a spot? No. Oh, but th—No. Sound familiar? You wouldn’t have to hear this if there were an alternative.

- Ethos: Maybe testimonies from former drivers who use public transit more often would be convincing: “In a survey of PSU students who switched from driving to public transit, 65% said they were not only confident in their choice, but that they were much happier as a result!”

- The Toulmin model of argumentation is another common framework and structure which is not discussed here. ↵

- Wetzel, John. “The MCAT Writing Assignment.” WikiPremed, Wisebridge Learning Systems LLC, 2013, http://www.wikipremed.com/mcat_essay.php. Reproduced in accordance with Creative Commons licensure. ↵

- I find this distinction especially valuable because there is some slippage in what instructors mean by “rhetorical triangle”—e.g., “logos, pathos, ethos” vs. “reader, writer, text.” The latter set of definitions, used to determine rhetorical situation, is superseded in this text by SOAP (subject, occasion, audience, purpose). ↵

- This correlation is an oft-cited example, but the graph is a fabrication to make a point, not actual data. ↵

- See Frederic Filloux’s 2016 article, “Facebook’s Walled Wonderland is Inherently Incompatible with News.” ↵

- See “Power and Place Equal Personality” (Deloria) or “Jasmine-Not-Jasmine” (Han) for non-comprehensive but interesting examples.Deloria, Jr., Vine. “Power and Place Equal Personality.” Indian Education in America by Deloria and Daniel Wildcat, Fulcrum, 2001, pp. 21-28.Han, Shaogang. “Jasmine-Not-Jasmine.” A Dictionary of Maqiao, translated by Julia Lovell, Dial Press, 2005, pp. 352 . ↵

a rhetorical mode in which different perspectives on a common issue are negotiated. See Aristotelian and Rogerian arguments

a neologism from ‘impartial,’ refers to occupying and appreciating a variety of perspectives rather than pretending to have no perspective. Rather than unbiased or neutral, multipartial writers are balanced, acknowledging and respecting many different ideas.

a mode of argument by which an author seeks compromise by bringing different perspectives on an issue into conversation. Acknowledges that no one perspective is absolutely and exclusively ‘right’; values disagreement in order to make moral, political, and practical decisions.

a means by which a writer or speaker connects with their audience to achieve their purpose. Most commonly refers to logos, pathos, and ethos.

a mode of argument by which a writer attempts to convince their audience that one perspective is accurate.

a rhetorical appeal to logical reasoning.

a rhetorical appeal to emotion.

a rhetorical appeal based on authority, credibility, or expertise.

a line of logical reasoning which follows a pattern of that makes an error in its basic structure. For example, Kanye West is on TV; Animal Planet is on TV. Therefore, Kanye West is on Animal Planet.

a line of logical reasoning which follows a pattern of that makes an error in its basic structure. For example, Kanye West is on TV; Animal Planet is on TV. Therefore, Kanye West is on Animal Planet.

the setting (time and place) or atmosphere in which an argument is actionable or ideal. Consider alongside “occasion.”