Chapter 2: Telling a Story

“We’re all stories, in the end.” – Steven Moffat, Doctor Who[1]

Whether or not you’ve seen a single episode of Doctor Who, you can appreciate this quote. I love it for its ambiguities. [2] As I can tell, we can interpret it in at least four ways:

- Each of us is a story, in the end. Your entire life, while composed of many interlocking stories, is one story among many.

- All of us are stories, in the end. Our stories are never just our own: you share common stories with your parents, your friends, your teachers and bosses, strangers on the street.

- All we are is stories, in the end. Our identities, our ambitions, our histories are all a composite of the many stories we tell about ourselves.

- We are stories (in all of the above ways), but only at the end. Our individual stories have no definite conclusion until we can no longer tell them ourselves. What legacy will you leave? How can you tell a piece of your story while it’s still up to you?

But perhaps that’s enough abstraction: narration is a rhetorical mode that you likely engage on a daily basis, and one that has held significance in every culture in human history. Even when we’re not deliberately telling stories, storytelling often underlies our writing and thinking:

- Historians synthesize and interpret events of the past; a history book is one of many narratives of our cultures and civilizations.

- Chemists analyze observable data to determine cause-and-effect behaviors of natural and synthetic materials; a lab report is a sort of narrative about elements (characters) and reactions (plot).

- Musical composers evoke the emotional experience of story through instrumentation, motion, motifs, resolutions, and so on; a song is a narrative that may not even need words.

What makes for an interesting, well-told story in writing? In addition to description, your deliberate choices in narration can create impactful, beautiful, and entertaining stories.

| characterization | the process by which an author builds characters; can be accomplished directly or indirectly. |

| dialogue | a communication between two or more people. Can include any mode of communication, including speech, texting, e-mail, Facebook post, body language, etc. |

| dynamic character | a character who noticeably changes within the scope of a narrative, typically as a result of the plot events and/or other characters. Contrast with static character. |

| epiphany | a character’s sudden realization of a personal or universal truth. See dynamic character. |

| flat character | a character who is minimally detailed, only briefly sketched or named. Generally less central to the events and relationships portrayed in a narrative. Contrast with round character. |

| mood | the emotional dimension which a reader experiences while encountering a text. Compare with tone. |

| multimedia / multigenre | a rhetorical mode involving the construction and relation of stories. Typically integrates description as a technique. |

| narration | a rhetorical mode involving the construction and relation of stories. Typically integrates description as a technique. |

| narrative pacing | the speed with which a story progresses through plot events. Can be influenced by reflective and descriptive writing. |

| narrative sequence | the speed with which a story progresses through plot events. Can be influenced by reflective and descriptive writing. |

| plot | the events included within the scope of a narrative. |

| point-of-view | the perspective from which a story is told, determining both grammar (pronouns) and perspective (speaker’s awareness of events, thoughts, and circumstances). |

| round character | a character who is thoroughly characterized and dimensional, detailed with attentive description of their traits and behaviors. Contrast with flat character. |

| static character | a character who remains the same throughout the narrative. Contrast with dynamic character. |

| tone | the emotional register of the text. Compare with mood. |

Techniques

Plot Shapes and Form

Plot is one of the basic elements of every story: put simply, plot refers to the actual events that take place within the bounds of your narrative. Using our rhetorical situation vocabulary, we can identify “plot” as the primary subject of a descriptive personal narrative. Three related elements to consider are scope, sequence, and pacing.

Scope

The term scope refers to the boundaries of your plot. Where and when does it begin and end? What is its focus? What background information and details does your story require? I often think about narrative scope as the edges of a photograph: a photo, whether of a vast landscape or a microscopic organism, has boundaries. Those boundaries inform the viewer’s perception. In this example, the scope of the left photo allows for a story about a neighborhood in San Francisco. In the middle, it is a story about the fire escape, the clouds. On the right, the scope of the story directs our attention to the birds. In this way, narrative scope impacts the content you include and your reader’s perception of that content in context.

The way we determine scope varies based on rhetorical situation, but I can say generally that many developing writers struggle with a scope that is too broad: writers often find it challenging to zero in on the events that drive a story and prune out extraneous information.

Consider, as an example, how you might respond if your friend asked what you did last weekend. If you began with, “I woke up on Saturday morning, rolled over, checked my phone, fell back asleep, woke up, pulled my feet out from under the covers, put my feet on the floor, stood up, stretched…” then your friend might have stopped listening by the time you get to the really good stuff. Your scope is too broad, so you’re including details that distract or bore your reader. Instead of listing every detail in order.

Consider narrowing your scope, focusing instead on the important, interesting, and unique plot points (events).

You might think of this as the difference between a series of snapshots and a roll of film: instead of twenty-four frames per second video, your entire story might only be a few photographs aligned together.

It may seem counterintuitive, but we can often say more by digging deep into a few ideas or events, instead of trying to relate every idea or event.

The most impactful stories are often those that represent something, so your scope should focus on the details that fit into the bigger picture. To return to the previous example, you could tell me more about your weekend by sharing a specific detail than every detail. “Brushing my teeth Saturday morning, I didn’t realize that I would probably have a scar from wrestling that bear on Sunday” reveals more than “I woke up on Saturday morning, rolled over, checked my phone, fell back asleep, woke up, pulled my feet out from under the covers, put my feet on the floor, stood up, stretched….” Not only have you foregrounded the more interesting event, but you have also foreshadowed that you had a harrowing, adventurous, and unexpected weekend.

Sequence and Pacing

The sequence and pacing of your plot—the order of the events and the amount of time you give to each event, respectively—will determine your reader’s experience. There are an infinite number of ways you might structure your story, and the shape of your story is worth deep consideration. Although the traditional forms for narrative sequence are not your only options, let’s take a look at a few tried-and-true shapes your plot might take.

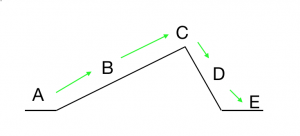

You might recognize Freytag’s Pyramid[3] from other classes you’ve taken:

A. Exposition: Here, you’re setting the scene, introducing characters, and preparing the reader for the journey.

B. Rising action: In this part, things start to happen. You (or your characters) encounter conflict, set out on a journey, meet people, etc.

C. Climax: This is the peak of the action, the main showdown, the central event toward which your story has been building.

D. Falling action: Now things start to wind down. You (or your characters) come away from the climactic experience changed—at the very least, you are wiser for having had that experience.

E. Resolution: Also known as dénouement, this is where all the loose ends get tied up. The central conflict has been resolved, and everything is back to normal, but perhaps a bit different.

This narrative shape is certainly a familiar one. Many films, TV shows, plays, novels, and short stories follow this track. But it’s not without its flaws. You should discuss with your classmates and instructors what shortcomings you see in this classic plot shape. What assumptions does it rely on? How might it limit a storyteller? Sometimes, I tell my students to “Start the story where the story starts”—often, steps A and B in the diagram above just delay the most descriptive, active, or meaningful parts of the story. If nothing else, we should note that it is not necessarily the best way to tell your story, and definitely not the only way.

How will your choices of narrative scope, sequence, and pacing impact your reader’s experience?

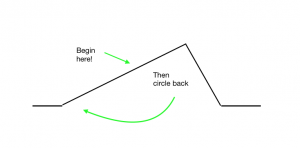

Another classic technique for narrative sequence is known as in medias res—literally, “in the middle of things.” As you map out your plot in pre-writing or experiment with during the drafting and revision process, you might find this technique a more active and exciting way to begin a story.

In the earlier example, the plot is chronological, linear, and continuous: the story would move smoothly from beginning to end with no interruptions. In medias res instead suggests that you start your story with action rather than exposition, focusing on an exciting, imagistic, or important scene. Then, you can circle back to an earlier part of the story to fill in the blanks for your reader. Using the previously discussed plot shape, you might visualize it like this:

-

In the middle of things - in medias res

-

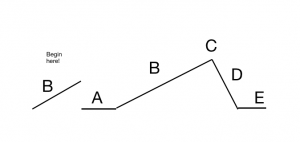

Creative structure - or a unique plot structure like D B A C E or E A B C D.

You can experiment with your sequence in a variety of other ways, which might include also making changes to your scope: instead of a continuous story, you might have a series of fragments with specific scope (like photographs instead of video), as is exemplified by “The Pot Calling the Kettle Black….” Instead of chronological order, you might bounce around in time or space, like in “Parental Guidance,” or in reverse, like “21.” Some of my favorite narratives reject traditional narrative sequence.

I include pacing with sequence because a change to one often influences the other. Put simply, pacing refers to the speed and fluidity with which a reader moves through your story. You can play with pacing by moving more quickly through events, or even by experimenting with sentence and paragraph length. Consider how the “flow” of the following examples differs:

| The train screeched to a halt. A flock of pigeons took flight as the conductor announced, “We’ll be stuck here for a few minutes.” | Lost in my thoughts, I shuddered as the train ground to a full stop in the middle of an intersection. I was surprised, jarred by the unannounced and abrupt jerking of the car. I sought clues for our stop outside the window. All I saw were pigeons as startled and clueless as I. |

I recommend the student essay “Under the Knife,” which does excellent work with pacing, in addition to making a strong creative choice with narrative scope.

Point-of-View

The position from which your story is told will help shape your reader’s experience, the language your narrator and characters use, and even the plot itself. You might recognize this from Dear White People Volume 1 or Arrested Development Season 4, both Netflix TV series. Typically, each episode in these seasons explores similar plot events, but from a different character’s perspective. Because of their unique vantage points, characters can tell different stories about the same realities.

This is, of course, true for our lives more generally. In addition to our differences in knowledge and experiences, we also interpret and understand events differently. In our writing, narrative position is informed by point-of-view and the emotional valences I refer to here as tone and mood.

Point-of-view (POV): the perspective from which a story is told.

This is a grammatical phenomenon—i.e., it decides pronoun use—but, more importantly, it impacts tone, mood, scope, voice, and plot.[4]

Although point-of-view will influence tone and mood, we can also consider what feelings we want to convey and inspire independently as part of our narrative position.

tone: the emotional register of the story’s language.

- What emotional state does the narrator of the story (not the author, but the speaker) seem to be in? What emotions are you trying to imbue in your writing?

mood: the emotional register a reader experiences.[5]

- What emotions do you want your reader to experience? Are they the same feelings you experienced at the time?

A Non-Comprehensive Breakdown of POV

| 1st person | Narrator uses 1st person pronouns (I/me/mine or us/we/ours) | Can include internal monologue (motives, thoughts, feelings) of the narrator. Limited certainty of motives, thoughts, or feelings of other characters. | I tripped on the last stair, preoccupied by what my sister had said, and felt my stomach drop. |

| 2nd person | Narrator uses 2nd person pronouns (you/you/your) | Speaks to the reader, as if the reader is the protagonist OR uses apostrophe to speak to an absent or unidentified person | Your breath catches as you feel the phantom step.

O, staircase, how you keep me awake at night. |

| 3rd person limited | Narrator uses 3rd person pronouns (he/him/his, she/her/hers, they/they/theirs) | Sometimes called “close” third person. Observes and narrates but sticks near one or two characters, in contrast with 3rd person omniscient. | He was visibly frustrated by his sister’s nonchalance and wasn’t watching his step. |

| 3rd person omniscient | Narrator uses 3rd person pronouns (he/him/his, she/her/hers, they/they/theirs) | Observes and narrates from an all-knowing perspective. Can include internal monologue (motives, thoughts, feelings) of all characters. | Beneath the surface, his sister felt regretful. Why did I tell him that? she wondered. |

| stream-of-consciousness | Narrator uses inconsistent pronouns, or no pronouns at all | Approximates the digressive, wandering, and ungrammatical thought processes of the narrator. | But now, a thousand empty⎯where?⎯and she, with head shake, will be fine⎯AHH! |

Typically, you will tell your story from the first-person point-of-view, but personal narratives can also be told from a different perspective; I recommend “Comatose Dreams” to illustrate this at work. As you’re developing and revising your writing, try to inhabit different authorial positions: What would change if you used the third person POV instead of first person? What different meanings would your reader find if you told this story with a different tone—bitter instead of nostalgic, proud rather than embarrassed, sarcastic rather than genuine?

Furthermore, there are many rhetorical situations that call for different POVs. (For instance, you may have noticed that this book uses the second-person very frequently.) So, as you evaluate which POV will be most effective for your current rhetorical situation, bear in mind that the same choice might inform your future writing.

Building Characters

Whether your story is fiction or nonfiction, you should spend some time thinking about characterization: the development of characters through actions, descriptions, and dialogue. Your audience will be more engaged with and sympathetic toward your narrative if they can vividly imagine the characters as real people.

Like description, characterization relies on specificity. Consider the following contrast in character descriptions:

| My mom is great. She is an average-sized brunette with brown eyes. She is very loving and supportive, and I know I can rely on her. She taught me everything I know. | vs | In addition to some of my father’s idiosyncrasies, however, he is also one of the most kind-hearted and loving people in my life. One of his signature actions is the ‘cry-smile,’ in which he simultaneously cries and smiles any time he experiences a strong positive emotion (which is almost daily).[6] |

How does the “cry-smile” detail enhance the characterization of the speaker’s parent?

- Character Traits

To break it down to process, characterization can be accomplished in two ways:

- Directly, through specific description of the character—What kind of clothes do they wear? What do they look, smell, sound like?—or,

- Indirectly, through the behaviors, speech, and thoughts of the character—What kind of language, dialect, or register do they use? What is the tone, inflection, and timbre of their voice? How does their manner of speaking reflect their attitude toward the listener? How do their actions reflect their traits? What’s on their mind that they won’t share with the world?

Thinking through these questions will help you get a better understanding of each character (often including yourself!). You do not need to include all the details, but they should inform your description, dialogue, and narration.

| Round characters… | are very detailed, requiring attentive description of their traits and behaviors. | Your most important characters should be round: the added detail will help your reader better visualize, understand, and care about them. |

| Flat characters… | are minimally detailed, only briefly sketched or named. | Less important characters should take up less space and will therefore have less detailed characterization. |

| Static characters… | remain the same throughout the narrative. | Even though all of us are always changing, some people will behave and appear the same throughout the course of your story. Static characters can serve as a reference point for dynamic characters to show the latter’s growth. |

| Dynamic characters… | noticeably change within the narrative, typically as a result of the events. | Most likely, you will be a dynamic character in your personal narrative because such stories are centered around an impactful experience, relationship, or place. Dynamic characters learn and grow over time, either gradually or with an epiphany. |

Dialogue[7]

Dialogue: communication between two or more characters.

Think of the different conversations you’ve had today, with family, friends, or even classmates. Within each of those conversations, there were likely preestablished relationships that determined how you talked to each other: each is its own rhetorical situation. A dialogue with your friends, for example, may be far different from one with your family. These relationships can influence tone of voice, word choice (such as using slang, jargon, or lingo), what details we share, and even what language we speak.

As we’ve seen above, good dialogue often demonstrates the traits of a character or the relationship of characters. From reading or listening to how people talk to one another, we often infer the relationships they have. We can tell if they’re having an argument or conflict, if one is experiencing some internal conflict or trauma, if they’re friendly acquaintances or cold strangers, even how their emotional or professional attributes align or create opposition.

Often, dialogue does more than just one thing, which makes it a challenging tool to master. When dialogue isn’t doing more than one thing, it can feel flat or expositional, like a bad movie or TV show where everyone is saying their feelings or explaining what just happened. For example, there is a difference between “No thanks, I’m not hungry” and “I’ve told you, I’m not hungry.” The latter shows frustration, and hints at a previous conversation. Exposition can have a place in dialogue, but we should use it deliberately, with an awareness of how natural or unnatural it may sound. We should be aware how dialogue impacts the pacing of the narrative. Dialogue can be musical and create tempo, with either quick back and forth, or long drawn out pauses between two characters. Rhythm of a dialogue can also tell us about the characters’ relationship and emotions.

We can put some of these thoughts to the test using the exercises in the Activities section of this chapter to practice writing dialogue.

Choosing a Medium

Narration, as you already know, can occur in a variety of media: TV shows, music, drama, and even Snapchat Stories practice narration in different ways. Your instructor may ask you to write a traditional personal narrative (using only prose), but if you are given the opportunity, you might also consider what other media or genres might inform your narration. Some awesome narratives use a multimedia or multigenre approach, synthesizing multiple different forms, like audio and video, or nonfiction, poetry, and photography.

In addition to the limitations and opportunities presented by your rhetorical situation, choosing a medium also depends on the opportunities and limitations of different forms. To determine which tool or tools you want to use for your story, you should consider which medium (or combination of media) will help you best accomplish your purpose. Here’s a non-comprehensive list of storytelling tools you might incorporate in place of or in addition to traditional prose:

- Images

- Poetry

- Video

- Audio recording

- “Found” texts (fragments of other authors’ works reframed to tell a different story)

- Illustrations

- Comics, manga, or other graphic storytelling

- Journal entries or series of letters

- Plays, screenplays, or other works of drama

- Blogs and social media postings

Although each of these media is a vehicle for delivering information, it is important to acknowledge that each different medium will have a different impact on the audience; in other words, the medium can change the message itself.

There are a number of digital tools available that you might consider for your storytelling medium, as well.[8]

Activities

Idea Generation: What Stories Can I Tell?

You may already have an idea of an important experience in your life about which you could tell a story. Although this might be a significant experience, it is most definitely not the only one worth telling. (Remember: first idea ≠ best idea.)

Just as with description, good narration isn’t about shocking content but rather about effective and innovative writing. In order to broaden your options before you begin developing your story, complete the organizer on the following pages.

Then, choose three of the list items from this page that you think are especially unique or have had a serious impact on your life experience. On a separate sheet of paper, free-write about each of your three list items for no less than five minutes per item.

- List five places that are significant to you (real, fictional, or imaginary)

- List ten people who have influenced your life in some way (positive or negative, acquainted or not, real or fictional)

- List ten ways that you identify yourself (roles, adjectives, or names)

- List three obstacles you’ve overcome to be where you are today

- List three difficult moments – tough decisions, traumatic or challenging experiences, or troubling circumstances

Idea Generation: Mapping an Autobiography

This exercise will help you develop a variety of options for your story, considered especially in the context of your entire life trajectory.

- First, brainstorm at least ten moments or experiences that you consider influential—moments that in some way impacted your identity, your friendships, your worldview—for the better or for the worse. Record them in the table below.

- Then, rate those experiences on a degree of “awesomeness,” “pleasurability,” or something else along those lines, on a scale of 0 – 10, with 10 being the hands down best moment of your life and 0 being the worst.

- Next, plot those events on graph paper. Each point is an event; the x-axis is your age, and the y-axis is the factor of positivity. Connect the points with a line.

- Finally, circle three of the events/experiences on your graph. On a clean sheet of paper, free-write about each of those three for at least four minutes.[9]

Experimenting with Voice and Dialogue[10]

Complete the following three exercises to think through the language your characters use and the relationships they demonstrate through dialogue. If you’ve started your assignment, you can use these exercises to generate content.

The Secret

- Choose any two professions for two imaginary characters.

- Give the two characters a secret that they share with one another. As you might imagine, neither of them would reveal that secret aloud, but they might discuss it. (To really challenge yourself, you might also come up with a reason that their secret must be a secret: Is it socially unacceptable to talk about? Are they liable to get in trouble if people find out? Will they ruin a surprise?)

- Write an exchange between those characters about the secret using only their words (i.e., no “he said” or “she said,” but rather only the language they use). Allow the secret to be revealed to the reader in how the characters speak, what they say, and how they say it. Pay attention to the subtext of what’s being said and how it’s being said. How would these characters discuss their secret without revealing it to eavesdroppers? (Consider Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” as a model.)

- Draw a line beneath your dialogue. Now, imagine that only one of the characters has a secret. Write a new dialogue in which one character is trying to keep that secret from the other. Again, consider how the speakers are communicating: what language do they use? What sort of tone? What does that reveal about their relationship?

The Overheard

- Go to a public space and eavesdrop on a conversation. (Try not to be too creepy—be considerate and respectful of the people.) You don’t need to take avid notes, but observe natural inflections, pauses, and gestures. What do these characteristics imply about the relationship between the speakers?

- Jot down a fragment of striking, interesting, or weird dialogue.

- Now, use that fragment of dialogue to imagine a digital exchange: consider that fragment as a Facebook status, a text message, or a tweet. Then, write at least ten comments or replies to that fragment.

- Reflect on the imaginary digital conversation you just created. What led you to make the choices you made? How does digital dialogue differ from real-life dialogue?

Beyond Words

As you may have noticed in the previous exercises, dialogue is about more than just what the words say: our verbal communication is supplemented by inflection, tone, body language, and pace, among other things. With a partner, exchange the following lines. Without changing the words, try to change the meaning using your tone, inflection, body language, etc.

| A | B |

| “I don’t want to talk about it.” | “Leave me alone.” |

| “Can we talk about it?” | “What do you want from me?” |

| “I want it.” | “You can’t have it.” |

| “Have you seen her today?” | “Why?” |

After each round, debrief with your partner; jot down a few notes together to describe how your variations changed the meaning of each word. Then, consider how you might capture and relay these different deliveries using written language—what some writers call “dialogue tags.” Dialogue tags try to reproduce the nuance of our spoken and unspoken languages (e.g., “he muttered,” “she shouted in frustration,” “they insinuated, crossing their arms”).

Using Images to Tell a Story

Even though this textbook focuses on writing as a means to tell stories, you can also construct thoughtful and unique narratives using solely images, or using images to supplement your writing. A single photograph can tell a story, but a series will create a more cohesive narrative. To experiment with this medium, try the following activity.

- Using your cell phone or a digital camera, take at least one photograph (of yourself, events, and/or your surroundings) each hour for one day.

- Compile the photos and arrange them in chronological order. Choose any five photos that tell a story about part or all of your day.

- How did you determine which photos to remove? What does this suggest about your narrative scope?

- Where might you want to add photos or text? Why?

To consider models of this kind of narrative, check out Al Jazeera’s “In Pictures” series. In 2014, a friend of mine recorded a one-second video every day for a year, creating a similar kind of narrative—you can check it out here.

- “The Big Bang.” Doctor Who, written by Steven Moffat, BBC, 2010. ↵

- Of interest on this topic is the word sonder, defined at The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows:(n.) the realization that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own—populated with their own ambitions, friends, routines, worries and inherited craziness—an epic story that continues invisibly around you like an anthill sprawling deep underground, with elaborate passageways to thousands of other lives that you’ll never know existed, in which you might appear only once, as an extra sipping coffee in the background, as a blur of traffic passing on the highway, as a lighted window at dusk.Koening, John. “Sonder.” The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, 22 July 2012, http://www.dictionaryofobscuresorrows.com/post/23536922667/sonder. ↵

- Gustav Freytag is credited with this particular model, often referred to as “Freytag’s pyramid.” Freytag studied the works of Shakespeare and a collection of Greek tragic plays to develop this model in Die Technik des Dramas (1863). ↵

- For the sake of brevity, I have not included here a discussion of focalization, an important phenomenon to consider when studying point-of-view more in-depth. ↵

- Sometimes tone and mood align, and you might describe them using similar adjectives—a joyous tone might create joy for the reader. However, they sometimes don’t align, depending largely on the rhetorical situation and the author’s approach to that situation. For instance, a story’s tone might be bitter, but the reader might find the narrator’s bitterness funny, off-putting, or irritating. Often, tone and mood are in opposition to create irony: Jonathan Swift’s matter-of-fact tone in “A Modest Proposal” is satirical, producing a range of emotions for the audience, from revulsion to hilarity. ↵

- Excerpt by an anonymous student author, 2016. Reproduced with permission from the student author. ↵

- Thanks to Alex Dannemiller for his contributions to this subsection. ↵

- Tips on podcasting and audio engineering: http://transom.org/Interactive web platform hosting: https://h5p.org/Audio editing and engineering: http://www.nch.com.au/wavepad/index.html Whiteboard video creation (paid, free trial): http://www.videoscribe.co/Infographic maker: https://piktochart.com/Comic and graphic narrative software (free, paid upgrades): https://www.pixton.com/ ↵

- This activity is a modified version of one by Lily Harris. ↵

- Thanks to Alex Dannemiller for his contributions to this subsection. ↵

a rhetorical mode involving the construction and relation of stories. Typically integrates description as a technique.

the events included within the scope of a narrative.

the topic, focus, argument, or idea explored in a text

Boundaries of your plot.

the order of events included in a narrative.

the amount of time you give each event

in the middle of things

the perspective from which a story is told, determining both grammar (pronouns) and perspective (speaker’s awareness of events, thoughts, and circumstances).

the emotional register of the text. Compare with mood.

the emotional dimension which a reader experiences while encountering a text. Compare with tone.

the process by which an author builds characters; can be accomplished directly or indirectly.

dialogue

a term describing a text that combines more than one media and/or more than one genre (e.g., an essay with embedded images; a portfolio with essays, poetry, and comic strips; a mixtape with song reviews).

a term describing a text that combines more than one media and/or more than one genre (e.g., an essay with embedded images; a portfolio with essays, poetry, and comic strips; a mixtape with song reviews).