5 Theory of Planned Behavior

Mary J. Ryan & Amber K. Worthington

Persuaders are oftentimes most interested in persuading others to adopt voluntary actions. An individual’s intentions to voluntarily behave in a particular way are most immediately determined by their intentions to do so. For example, getting someone to meditate will, at a bare minimum, require them to intend to meditate. One key issue within persuasion is therefore to determine what influences behavioral intentions. The Theory of Reasoned Action, and its extension the Theory of Planned Behavior, are commonly used theories of persuasion that explain what variables predict behavioral intentions.

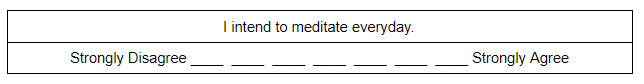

The Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) posits that behavior is directly determined by an individual’s behavioral intentions. In other words, as an individual’s intentions to perform a behavior increase, they are more likely to actually perform the behavior. Behavioral intentions are oftentimes assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

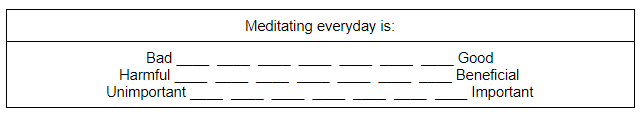

The Theory of Reasoned Action posits that intentions are directly predicted by (1) an individual’s attitude towards the behavior and (2) subjective norms. An attitude is defined as an individual’s evaluation of a given behavior. Someone might have a positive, negative, or neutral attitude about a given behavior. As an individual’s attitude becomes more positive, their intentions to perform a behavior will increase. Attitudes are oftentimes assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

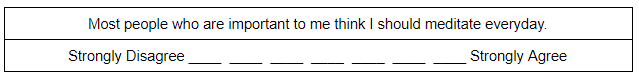

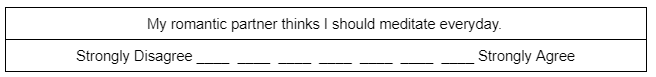

Subjective norms are defined as an individual’s beliefs about the importance others place on them performing a given behavior. In other words, it is the degree to which an individual perceives that other people want them to engage in the behavior. As an individual’s subjective norms increase, their intentions to perform a behavior will increase. Subjective norms are oftentimes assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

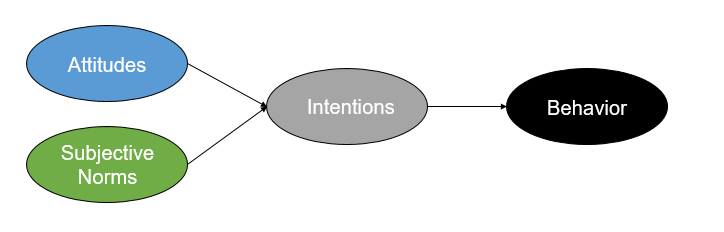

The Theory of Reasoned Action is depicted below:

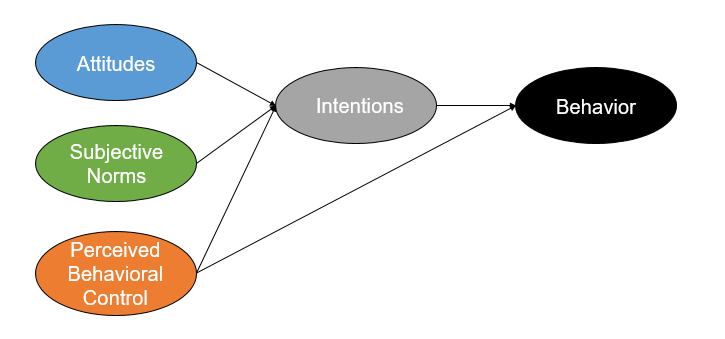

The Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1988, 1991) extends the Theory of Reasoned Action by including perceived behavioral control. The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that a behavior is directly determined by an individual’s intentions and perceived behavioral control. Perceived behavioral control, also referred to as self-efficacy, encompasses the extent to which an individual believes they have control over performing that behavior. Intentions, in turn, are directly predicted by (1) an individual’s attitude towards the behavior, (2) subjective norms, and (3) perceived behavioral control. Perceived behavioral control is oftentimes assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

The Theory of Planned Behavior is depicted below:

How are the predictors weighted in the Theory of Planned Behavior?

Attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control do not always contribute equally to predicting intentions. Sometimes, an individual’s intentions may be determined largely by attitudes, and subjective norms may have little or no influence. Other times, an individual’s intentions may be determined largely by subjective norms, and attitudes may have little or no influence. For example, college students’ intentions to meditate may largely be driven by their attitudes that meditating everyday is good, beneficial, and important; whether or not other people think they should meditate may not influence their intentions as strongly. The only way to determine the relative importance of (or weighting) of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control on intentions is to measure these variables across a group of study participants and run a statistical analysis.

What influences the relationship between intentions and behavior?

The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that intentions lead to behavior; however, intentions do not always guarantee behavior. For example, someone might intend to meditate everyday but not follow through. There are several factors that influence the strength of the relationship between intentions and behavior.

First, the Theory of Planned Behavior underscores a principle of specificity. This means that in order to best predict behavior, the attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control beliefs must relate to specific intentions and a subsequent specific behavior. These frameworks note that any given behavior includes an action, target, context and time period. For example, a goal might be “to meditate for 20 minutes before bed each day in the upcoming month.” In this example, “meditating” is the action, “20 minutes” is the target, “before bed each day” is the context, and “in the upcoming month” is the time period. As the specificity of the behavior increases, intentions become a better predictor of behavior.

Additionally, the temporal stability of intentions influences the strength of the relationship between intentions and behavior. If an individual’s intentions fluctuate over time (e.g., some days I intend to meditate, and other days I do not), then intentions measured at one particular time might not predict subsequent behavior (e.g., Rhodes & Dickau, 2013). As the stability of an individual’s intentions increases over time, intentions become a better predictor of behavior.

What additional predictors have been examined in the Theory of Planned Behavior?

The Theory of Planned Behavior focuses on rational reasoning and excludes the role of emotional and subconscious influences (see, e.g., Sniehotta, Presseau, & Araújo-Soares, 2014). Scholars have argued for the importance of these variables and have therefore suggested that anticipated emotions and past, habitual behaviors should be added to the Theory of Planned Behavior to better predict intentions and subsequent behavior.

People anticipate the emotions they will experience after performing a particular behavior — for example, an individual might anticipate feeling regret, guilt, or pride if they do or do not perform a given behavior. Anticipated emotions can therefore shape and motivate behaviors as people strive to avoid negative feelings and attain positive feelings (Baumeister, Vohs, DeWall, & Zhan 2007; O’Keefe, 2065). Past research has found that anticipated emotions have added to the explanatory power of the Theory of Planned Behavior for predicting, for example, cancer screening (McGilligan, McClenahan, & Adamnson, 2009), vaccination (Gallagher & Povey, 2006), seat belt use (Şimşekoğlu & Lajunen), caregiving behaviors (Tracy & Robins, 2004), bone marrow donation (Lindsey, Yun, & Hill, 2007), and organ donor registration (Wang, 2011).

Specific anticipated emotions that have been studied include anticipated regret, guilt, and pride. For example, one meta-analysis found that anticipated regret added significantly and independently to the prediction of both intentions and prospective behavior over and above Theory of Planned Behavior variables (Sandberg & Conner, 2008). Past research also notes that people will avoid actions that they anticipate will make them feel guilty. Thus anticipated guilt serves as an important predictor of intentions (O’Keefe, 2002). Finally, anticipated pride can impact intentions and behaviors, specifically for behaviors that conform to social standards and prosocial behaviors (Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007; Tracey & Robins, 2004).

Past behavior can have a significant influence on future behavior, specifically when the past behavior is habitual or routine (Ouellette & Wood, 1998; Sniehotta, 2014). This habitual behavior is oftentimes automatic instead of fully intentional and thus can influence intentions themselves or directly influence behavior by sidestepping intentions. As the behavior becomes more habitual, the relationship between past behavior and future behavior increases. Past research has found this to be the case for, for example, cancer screening (Norman & Cooper, 2011), riding a bicycle (de Bruijn & Gardner, 2011), eating behaviors (de Bruijn, 2010; de Bruijn, Kroeze, Oenema, & Brug, 2008), exercise (de Bruijn & Rhodes, 2010), and alcohol consumption (Norman & Conner, 2006).

How can the Theory of Planned Behavior be used to create persuasive messages?

The Theory of Planned Behavior specifies that it is possible to change someone’s intentions by influencing one or more of the three determinants of intentions (attitudes, subjective norms, and/or perceived behavioral control).

Attitudes

An individual’s attitude towards a given behavior could be influenced in a number of different ways. The Theory of Planned Behavior specifies the determinants of attitudes, which are useful to identify specific strategies to do so.

The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that an individual’s attitudes towards a given behavior are a joint function of their evaluation of each belief about the behavior and the strength with which each belief is held. The strength of a belief can be assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

The evaluation of each belief can be assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

Changing an individual’s attitudes could therefore be achieved by changing the evaluation of an existing salient belief. This might involve increasing the salience of an existing negative belief (e.g., “You probably already know that anxiety can be harmful, but you may not realize just how consequential it really can be””) or decreasing the salience of an existing positive belief (e.g., “Maybe you think your anxiety helps motivate you to complete your work, but there are other ways to accomplish your tasks”).

Changing an individual’s attitudes could also be achieved by changing the strength of an existing salient belief. This might involve increasing the belief strength of an existing positive belief (e.g, “You probably already know that meditation can reduce anxiety, but maybe you don’t realize just how likely it is to decrease”) or decreasing the belief strength of an existing positive belief (e.g., “Anxiety won’t actually motivate you to complete your work”).

Finally, changing an individual’s attitudes could be achieved by adding a new salient belief. This can be accomplished by providing the individual with additional information about the behavior and outcome of interest (e.g., “You might not realize that anxiety can increase your risk of heart disease”).

Subjective Norms

An individual’s subjective norms about a given behavior could be influenced in a number of different ways. The Theory of Planned Behavior specifies the determinants of subjective norms, which are useful to identify specific strategies to do so.

The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that an individual’s subjective norms about a given behavior are a joint function of their evaluation of normative beliefs that they ascribe to important others and their motivation to comply with those others. An individual’s normative beliefs can be assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

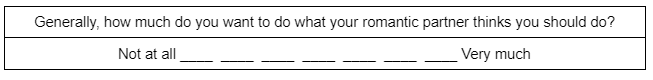

The motivation to comply with those important others can be assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

Changing an individual’s subjective norms could therefore be accomplished by increasing the salience of a particular referent (e.g., “Have you considered whether your girlfriend thinks it is important for you to decrease your anxiety and meditate everyday?”), changing the normative belief associated with a specific reference (e.g., “You’re actually wrong – I talked to your girlfriend, and she thinks you should meditate everyday to decrease your anxiety”), or altering the motivation to comply with a current referent (e.g., “You should really consider what she thinks about this”).

Perceived Behavioral Control

An individual’s perceived behavioral control for a given behavior could be influenced in a number of different ways. The Theory of Planned Behavior specifies the determinants of perceived behavioral control, which are useful to identify specific strategies to do so.

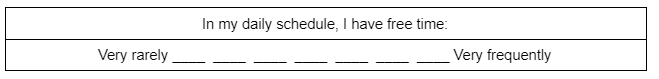

The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that an individual’s perceived behavioral control for a given behavior are a joint function of their assessment of the likelihood or frequency that a specific control factor will occur and the potential for the control factor to impede or facilitate the behavior. An individual’s assessment of the likelihood or frequency that a given control factor will occur can be assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

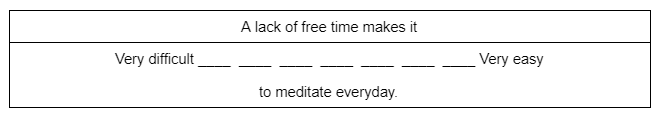

The potential for the control factor to impede or facilitate the behavior can be assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

Changing an individual’s perceived behavioral control can be accomplished in many ways. The persuader could directly remove the obstacle, create the opportunity for successful performance of the given behavior (e.g., “I’ve done it before, so I can do it again”), provide examples of others who have successfully performed the behavior (e.g., “If they can do it, I can do it”), or provide verbal encouragement (e.g., “You can do it!”; O’Keefe, 2016). Any of these strategies individually, or concurrently, could influence an individual’s assessment of the control factor, thus positively influencing their perceived behavioral control.

References

Abraham, C., & Sheeran, P. (2003). Acting on intentions: The role of anticipated regret. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42(4), 495-511.

Abraham, C., & Sheeran, P. (2004). Deciding to exercise: The role of anticipated regret. British Journal of Health Psychology, 9(2), 269-278.

Ajzen, I. (1988) Attitudes, personality and behaviour. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., Nathan DeWall, C., & Zhang, L. (2007). How emotion shapes behavior: Feedback, anticipation, and reflection, rather than direct causation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 167-203.

de Bruijn, G. J. (2010). Understanding college students’ fruit consumption: Integrating habit strength in the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite, 54(1), 16-22.

de Bruijn, G. J., & Gardner, B. (2011). Active commuting and habit strength: an interactive and discriminant analyses approach. American Journal of Health Promotion, 25(3), e27-e36.

de Bruijn, G. J., Kroeze, W., Oenema, A., & Brug, J. (2008). Saturated fat consumption and the Theory of Planned Behaviour: Exploring additive and interactive effects of habit strength. Appetite, 51(2), 318-323.

de Bruijn, G. J., & Rhodes, R. E. (2011). Exploring exercise behavior, intention and habit strength relationships. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 21(3), 482-491.

Gallagher, S., & Povey, R. (2006). Determinants of older adults’ intentions to vaccinate against influenza: A theoretical application. Journal of Public Health, 28(2), 139-144.

Lindsey, L. L. M., Yun, K. A., & Hill, J. B. (2007). Anticipated guilt as motivation to help unknown others: An examination of empathy as a moderator. Communication Research, 34(4), 468-480.

McGilligan, C., McClenahan, C., & Adamson, G. (2009). Attitudes and intentions to performing testicular self-examination: Utilizing an extended theory of planned behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44(4), 404-406.

Norman, P., & Conner, M. (2006). The theory of planned behaviour and binge drinking: Assessing the moderating role of past behaviour within the theory of planned behaviour. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11(1), 55-70.

Norman, P., & Cooper, Y. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour and breast self-examination: Assessing the impact of past behaviour, context stability and habit strength. Psychology & Health, 26(9), 1156-1172.

O’Keefe, D. J. (2016). Persuasion: Theory and Research (Third Edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Ouellette, J. A., & Wood, W. (1998). Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 124(1), 54.

Rhodes, R. E., & Dickau, L. (2013). Moderators of the intention-behaviour relationship in the physical activity domain: a systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(4), 215-225.

Riggio, R. E., Watring, K. P., & Throckmorton, B. (1993). Social skills, social support, and psychosocial adjustment. Personality and Individual Differences, 15(3), 275-280.

Sandberg, T., & Conner, M. (2008). Anticipated regret as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta‐analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47(4), 589-606.

Şimşekoğlu, Ö., & Lajunen, T. (2008). Social psychology of seat belt use: A comparison of theory of planned behavior and health belief model. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 11(3), 181-191.

Sniehotta, F., Presseau, J., & Araújo-Soares, V. (2014). Time to retire the theory of planned behavior. Health Psychology review, 8(1), 1-7.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). What’s moral about the self-conscious emotions. In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), The self-conscious emotions: Theory of research (pp. 21-37). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2004). Show your pride: Evidence for a discrete emotion expression. Psychological Science, 15(3), 194-197.

Wang, X. (2011). The role of anticipated guilt in intentions to register as organ donors and to discuss organ donation with family. Health Communication, 26(8), 683-690.