2 Theoretical Frameworks for Persuasion

Amber K. Worthington

We use theories to interpret the complex and ambiguous world around us. For example, theories help us understand health and illness, self-control, creativity, religion, spirituality, biology, physics, psychology, sociology, and, yes, persuasion. This chapter distinguishes between three types of commonly used theories: lay theories, folk theories, and scientific theories.

Lay and folk theories are informal, common-sense explanations used to understand various phenomena. Lay theories tend to be individual and idiosyncratic, whereas folk theories are shared by specific subgroups of people. Let’s start with an example that illustrates lay theories: Obesity is a prevalent global public health concern. Each of you may have your own lay theory about what causes obesity as well as how to treat obesity. You might believe that obesity is caused by a lack of knowledge, and therefore you might believe it is necessary to educate individuals to treat obesity. Someone else might believe that obesity is caused by a lack of access to healthy foods, and therefore might believe it is necessary to increase access to affordable healthy foods to treat obesity. These are lay theories, as they are based on our individual experiences and beliefs.

Now, let’s use the same topic, obesity, to explore example scenarios of folk theories. Some groups of people in the United States may believe that obesity is caused by individuals making poor choices and therefore would be solved by individuals making better choices. Other groups of people in the United States believe that obesity is caused by environmental factors and therefore would be solved by changing the environmental characteristics (e.g., unsafe neighborhoods, lack of access to healthy food) that promote obesity. As these are beliefs held by subgroups of the larger population, they would be considered folk theories.

Conversely, scientific theories are derived and tested from empirical observations. They are used to produce hypotheses, generate discoveries, and offer practical guidance. To continue with the above examples, there are many scientific theories used to understand obesity. For example, the biomedical perspective focuses on the pathophysiology and other biological approaches to the health condition. Examining obesity using this biomedical perspective would include observing the biological underpinnings of the disease (e.g., metabolism, cholesterol levels, thyroid functioning). The biopsychosocial perspective emphasizes the importance of understanding human health and wellness from a more holistic point of view that includes the biological, psychological, and social determinants of health. Examining obesity using this biopsychosocial perspective would include observing various psychological determinants of obesity (e.g., depression, anxiety) and/or social determinants of obesity (e.g., cultural food preferences, access to healthy foods).

Now that we’ve introduced lay, folk, and scientific theories generally, let’s turn to looking specifically at the discipline of persuasion. There are lay, folk, and scientific theories regarding how to best persuade someone to adopt a particular mental state or behavior. For example, you might personally believe that people do not know enough about factors that cause obesity, and, therefore, you may try to provide them with information in order to persuade them to adopt healthy behaviors (a lay theory of persuasion). Many public health organizations (a subgroup of people) hold a similar folk theory and have disseminated public health campaigns designed to increase knowledge about obesity and persuade people to adopt health behaviors (a folk theory of persuasion); however, scholars who study persuasion from a scientific perspective recognize that persuading someone to change their behaviors is not always as simple as these lay and folk theories suggest and instead apply scientific theories to understand persuasion.

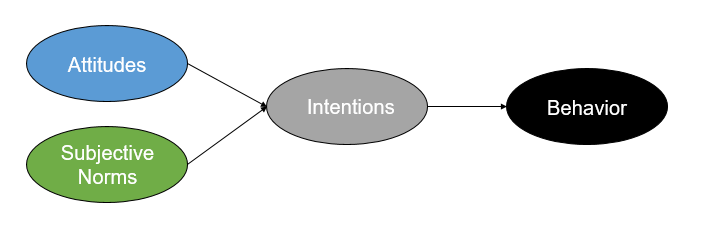

A scientific theory used in persuasion can be defined as an abstract system of concepts and their relationships that help us understand a phenomenon. For instance, persuasion researchers have observed that many people know that exercise and healthy foods would prevent and treat obesity, yet they still do not engage in those behaviors. Persuasion researchers therefore use these observations, and others, to create scientific theories about persuasion. For example, the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) is shown in the diagram below.

The Theory of Reasoned Action predicts that behavior is directly determined by an individual’s intentions to engage in the behavior. The arrow that goes from intentions to behavior shows this relationship. Intentions, in turn, are directly predicted by (1) an individual’s attitudes towards the behavior (i.e., the individual’s evaluation of the behavior as positive or negative) and (2) subjective norms (i.e., an individual’s perceptions of whether or not important others think they should engage in the behavior). The arrows that go from attitudes and subjective norms to intentions depict these relationships.

Let’s focus on one behavior related to obesity: exercising daily. The Theory of Reasoned Action suggests that an individual’s exercising daily (behavior) is directly predicted by their intentions to exercise daily (intentions). These intentions, in turn, are predicted by the individual’s attitudes towards exercising daily (e.g., “I think exercising daily is important/important”) and subjective norms (e.g., “I think my spouse thinks I should exercise daily). In order to persuade someone to start exercising daily, the Theory of Reasoned Action suggests that you would need to change the individual’s attitudes and subjective norms about exercising daily. This change in attitudes and subjective norms is predicted to positively influence intentions to exercise daily, which then positively influence their performance of the behavior itself.

Remember that a scientific theory can be defined as an abstract system of concepts and their relationships that help us understand a phenomenon. The Theory of Reasoned Action includes four concepts (attitudes, subjective norms, intentions, and behavior), as well as the relationships between those concepts (behavior is predicted by intentions, and intentions are predicted by attitudes and subjective norms). The Theory of Reasoned Action is just one example of the many different scientific theories used when studying persuasion. More broadly, a scientific theory should meet five basic characteristics:

#1: Testable: Scientific theories are tested through a series of scientific studies. Sometimes the evidence supports the theory, and sometimes the evidence fails to support the theory. The important thing is that it has to be possible to gather empirical evidence to test the theory’s proposed relationships.

#2: Replicable: Scientific studies that examine scientific theories should be able to be copied or reproduced exactly. This means that there must be enough information readily available about the theory so that others can test the theory as well.

#3: Stable: Scientific theories should stand the test of time. In other words, when other people test the theories, they should get the same results. If they do not, the theory may need to be revised based on the newly acquired evidence.

#4: Simple (aka Parsimonious): Scientific theories should be as simple as possible. The principle of parsimony states that a scientific theory should provide the simplest possible explanation for the phenomenon. As we will see later in this book, persuasion researchers noticed that the Theory of Reasoned Action failed to explain several aspects of intentions and behaviors and therefore added additional concepts to the theory, which later became the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1988, 1991). This made the theory less simple, but it is now better able to predict behavior.

#5: Consistent: Scientific theories should agree with other scientific theories, meaning that a principle in one theory should not directly contradict another. When inconsistencies do occur, scientific studies should be used to gather evidence to address and amend the discrepancy.

What is Persuasion Theory?

Using this understanding of scientific theory, we can apply it to persuasion. “Persuasion theory” can be defined as an abstract system of concepts and their relationships that help us understand persuasion. Additionally, considering our previously arrived upon paradigm cases of persuasion in Chapter 1, persuasion theory is defined as an abstract system of concepts and their relationships that help us understand a successful, intentional effort at influencing another’s mental state through communication in a situation in which the person being influenced has some measure of freedom.

References

Ajzen, I. (1988) Attitudes, personality and behaviour. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.