3 Persuasion Research Articles

Amber K. Worthington

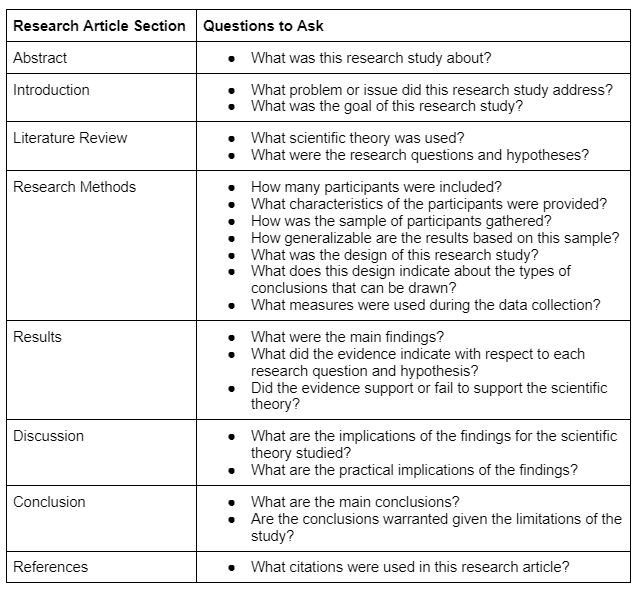

The study of persuasion requires you to read, understand, interpret, and synthesize persuasion research articles that have been published in academic journals. Without extensive training in research methods and analysis, this can sometimes seem like a daunting task. The goal of this chapter is therefore to provide you with some basic background information on key things to look for when reading a scientific article. Research articles usually include the following components: (1) abstract, (2) introduction, (3) literature review, (4) research methods, (5) results, (6) discussion, (7) conclusion, and (8) references. There are key pieces of information to look for in each section, which are detailed below and summarized in the table at the end of this chapter. This chapter uses this sample research article to provide an example:

Karnowski, V., Leonhard, L., & Kümpel, A. S. (2018). Why users share the news: A theory of reasoned action-based study on the antecedents of news-sharing behavior. Communication Research Reports, 35(2), 91-100.

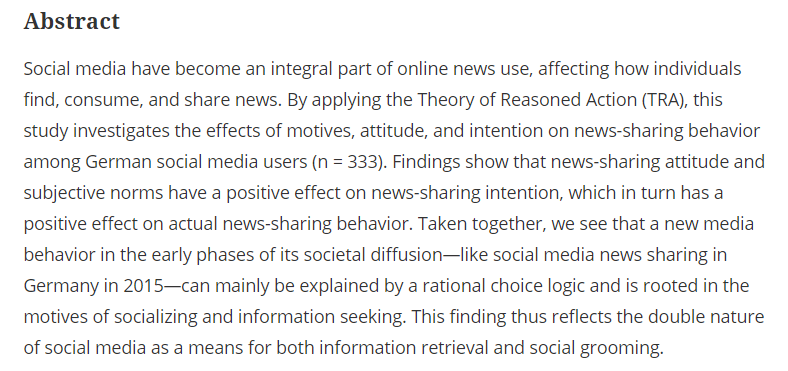

Abstract

The abstract is the first part of the article you will see and is usually a very short paragraph. The abstract summarizes the topic and purpose of the study, the scientific theory guiding the research, the methods (e.g., participants, research design), the main findings, and the conclusions. The abstract is a great place to start to get a general sense of what the research article is about.

Karnowski et al., 2018 Example: The abstract is a freely accessible portion of the research article and is therefore provided below. You will need to use your university access to read the remainder of the article.

As you can see, this abstract provides information about the topic of the study (i.e., social media and news consumption). This abstract also clearly states the scientific theory used to guide the research (i.e., the Theory of Reasoned Action). This abstract does indicate that 333 German social media users were included in the study, but it does not include the study design. The abstract provides information about the main findings (i.e., news-sharing attitudes and subjective norms influence intentions, which, in turn, influence behavior). The abstract also includes the authors’ conclusions about the use of social media for information retrieval and social grooming.

Introduction & Literature Review

The introduction section includes the main background information on the topic being investigated as well as the main goals for the research study. The literature review section analyzes, synthesizes, and incorporates scholarly research that has previously been done on the topic. The literature review also describes the scientific theory being used to guide the study (also referred to as the theoretical framework), summarizes previous empirical work on the scientific theory, and includes any proposed extensions to the scientific theory that the study examined. This section also includes the research questions and hypotheses, which should stem from the relationships between the concepts articulated in the scientific theory. Sometimes, the introduction and literature review sections are presented together, and other times they are presented as separate sections. They also may or may not be labeled “Introduction” and/or “Literature Review.”

Karnowski et al., 2018 Example: This article does not label its sections “Introduction” or “Literature Review” and instead jumps right into providing the introduction information. The authors introduce the topic of rising social media use and news sharing via social media. The authors clearly state that they are using the Theory of Reasoned Action. They include a summary of the Theory of Reasoned Action as well as previous relevant research. There are three hypotheses that stem directly from the Theory of Reasoned Action:

H2: Subjective norms will have a positive influence on news-sharing intentions.

H3: News-sharing attitudes will have a positive influence on news-sharing intentions.

H4: News-sharing intentions will have a positive influence on news-sharing behaviors.

The authors also propose some theoretical extensions, which are evident in the remaining hypothesis and research questions.

Research Methods

The research methods section may be called a variety of different things: “Methods,” “Methodology,” or “Materials and Methods” are commonly used. The research methods section contains key information on the participants included in the study, the design of the study, and the measures used to collect the data.

There are several important things to look for with respect to the participants. You should look for the total number of participants, the characteristics of the participants, and the sampling method used to gather the participants. The total number of participants can vary widely, but is almost always provided. The research article should also provide some demographic information about the participants (e.g., gender, age, political affiliation, or any other information relevant to the topic). It is impossible to collect information on every possible demographic, so the researchers decided what information to collect and what information to present in the research article that they believed was relevant (e.g., sometimes political affiliation may be related to the topic, and sometimes it may not).

There are many, many different types of sampling methods, and this chapter only provides a very basic starting point. The type of sampling method determines the generalizability of the results. To simplify, we will focus on two overarching sampling methods: a convenience sample and a simple random sample. Most persuasion research studies use a convenience sample. With a convenience sample, the researchers gather their participants from a group of people who are easy to contact or reach (e.g., from an undergraduate course, an online posting to a survey link, a clinic closeby). It is important to note that with a convenience sample, the results of the study cannot be generalized to the broader population. For example, a sample of 500 women who live in Alaska who were recruited from an online database is a convenience sample. The results of this study can only technically be applied to those 500 women included in the research study. Persuasion researchers often try to generalize the results to other people with the same characteristics (e.g., women in Alaska); however, they absolutely cannot say that their conclusions apply to all people in Alaska, all women in the United States, or any larger population. Even when generalizing the results to other people with the same characteristics, it is important to look at whether the sample represents the population with respect to different racial and cultural groups, sexual orientations, gender identities, and so on.

A random sample is a subset of individuals chosen from a larger set in which all individuals have an equal chance of being selected to be included in the sample. In order to have a simple random sample, the researchers would first need an entire list of everyone in the population they wanted to study. They would then need to randomly select participants from that list, where each person would have the same chance of being selected. For example, if a researcher wanted to study undergraduate students at the University of Alaska Anchorage using a simple random sample, they would first need to create a list of every current undergraduate student. They would then need to randomly select undergraduate students from that list to be part of their sample. A random sample is often very difficult to achieve, as it is difficult (and sometimes impossible) to find a list of all the people in the population of interest. Thus, more often than not, researchers use a convenience sampling method. The results from a study that uses random sampling can, importantly, generalize the results back to the population from which their sample was drawn.

There are also many, many different types of study designs, and, again, this chapter only provides a very basic starting point. The type of study design determines the types of conclusions that can be drawn from the results. To simplify, we will focus on two overarching types of study designs: an observational design and an experimental design. With an observational design, the researchers measure or survey the participants without trying to affect them. For example, if I hypothesize that exercise is related to a healthy weight, an observational study design could ask participants to report how often they exercise and how much they weigh. An observational design can make conclusions about whether or not the variables are related or correlated (in this example, whether exercise and weight are related). An observational design cannot make conclusions about causality or whether one variable caused another. Some key words that would indicate that a study has an observational design include “cross sectional,” “case-control,” and “cohort.”

With an experimental design, the researchers manipulate one variable of interest (referred to as the independent variable) and see how that affects another variable (referred to as the dependent variable). For example, if I hypothesize that exercise causes a healthy weight, an experimental study design could place participants into two different groups: one that engages in an exercise program and one that does not. After affecting the participants’ exercise in this way, the researchers could then compare the weight of the participants in the exercise program with the weight of the participants who were not. An experimental design can make conclusions about whether or not variation in one variable causes a change in another variable.

The final thing to look for in the research methods section is the type of measures the researchers used to measure their variables of interest. Some variables can be measured objectively. For example, objective measures could include someone’s weight, the number of hours they exercise per week, and so on. Many variables within persuasion, however, are measured subjectively. In these instances, researchers will ask participants a series of questions designed to understand something not readily observable. For example, subjective measures could include someone’s attitude towards a behavior, their subjective norms, and their intentions to perform the behavior. There are many limitations to self-report measures, both objective and subjective, as they rely upon accurate reporting by the participants themselves.

Karnowski et al., 2018 Example: This article has a section labeled “Method” with subsections for the “Design and Sample” and “Measures.” The article states that the sample included 333 German social media users and provided information about their age, gender, and education level. The article notes that the participants were recruited from Twitter and Facebook pages of a popular German news outlet. This is a convenience sample, so technically the results apply only to those people who participated in the study; however, it may be possible to generalize the results to other German social media users with similar demographics.

The article notes that the data were collected through a German language online survey. The article does not mention an intervention, nor does it appear as if the researchers attempted to affect the participants’ attitudes, subjective norms, or intentions. Therefore, this is an observational design. This means that the authors can make conclusions about correlations, not causations.

The article used subjective measures and asked participants to respond to a series of questions designed to measure their news-sharing attitudes, subjective norms, and intentions. They also used an objective measure and asked participants to report how often they shared the link to a news article on social media in the last week, which was a measure of their actual behavior. Both of these measures are limited as they rely on the participants to self-report.

Results

The results section presents the data analysis techniques and the main findings. You should look specifically to see whether the evidence supported or failed to support the hypotheses and research questions of interest.

Karnowski et al., 2018 Example: The authors note that they used regression analyses to examine H2, H3, and H4. They found support for each of these hypotheses, which in turn finds support for the Theory of Reasoned Action.

Discussion

The discussion section contextualizes the results of the research study within the broader context of the research thus far conducted on the topic and the scientific theory. This will oftentimes include a discussion of the implications of the findings for the scientific theory used, as well as the practical implications of the findings in real-world applications. The discussion section also usually includes a section on the limitations of the research study, as well as directions for future research.

Karnowski et al., 2018 Example: The authors found support for the Theory of Reasoned Action when examining news sharing on social media in a sample of German social media users. The authors further examine the practical implications of their results by discussing potential explanations for their results with respect to news sharing on social media (specifically the dual nature of social media as a means for both information retrieval and social grooming). The authors include a section on the limitations, including their sample and variables they did not measure, including type of news shared and habits/automated behaviors.

Conclusion(s)

The conclusion(s) section will usually contain a brief summary of the main findings and implications of the research study.

Karnowski et al., 2018 Example: The authors conclude that news sharing on social media in Germany in 2015 can be explained using the Theory of Reasoned Action. The authors could be more specific that the results apply specifically to their sample as well.

References

The references section provides and cites all of the sources referenced in the research article. This is a great place to go to find additional reading on the topic and/or scientific theory.

References

Karnowski, V., Leonhard, L., & Kümpel, A. S. (2018). Why users share the news: A theory of reasoned action-based study on the antecedents of news-sharing behavior. Communication Research Reports, 35(2), 91-100.