6 Technology Acceptance Model

Georgia L. Burgess & Amber K. Worthington

The Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989; Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989) evolved from the Theories of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior that were introduced in Chapters 4 and 5. This original inception of the Technology Acceptance Model stated that the goal of this theory was to “provide an explanation of the determinants of computer acceptance that is general, capable of explaining user behavior across a broad range of end-user computing technologies and user populations, while at the same time being both parsimonious and theoretically justified” [Davis et al. 1989, p. 985]. The use of the Technology Acceptance Model has since been expanded to include various other technologies beyond computers, including use of telemedicine services (Kamal, Shafiq, & Kakria, 2020), digital technologies for teachers (Scherer, Siddiq, & Tondeur, 2019), phone apps (Min, So, & Jeong, 2019), and e-learning platforms for students (Sukendro et al., 2020).

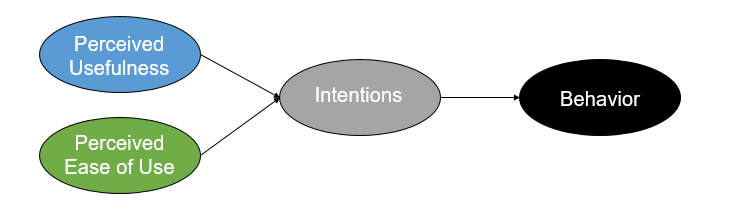

The Technology Acceptance Model is depicted below:

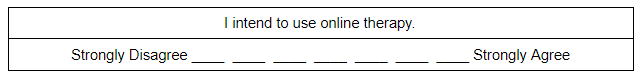

The Technology Acceptance Model posits that actual technology use is directly determined by an individual’s intentions to use the technology. As the individual’s intentions to use the technology increase, they are more likely to actually use the technology. Let’s use online therapy as an example. Technology use intentions are oftentimes assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

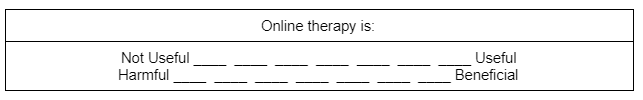

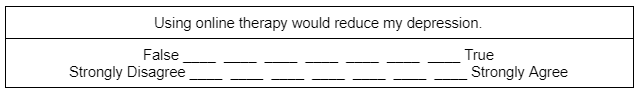

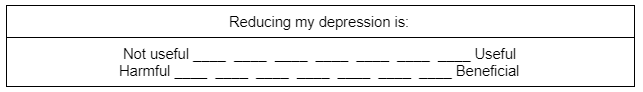

The Technology Acceptance Model further predicts that these intentions are directly predicted by (1) an individual’s perceived usefulness of the technology and (2) an individual’s perceived ease of use of the technology. Perceived usefulness is defined as the degree to which an individual believes that using a particular technology would be beneficial. As an individual’s perceived usefulness of a given technology increases, their intentions to use the technology also increase. Perceived usefulness is oftentimes assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

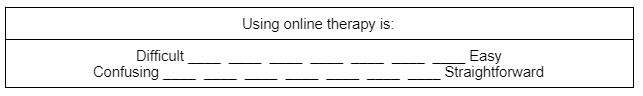

Perceived ease of use is defined as the degree to which an individual believes that using a particular technology would be free from effort. As an individual’s perceived ease of use of using a given technology increases, their intentions to use the technology also increase. Perceived ease of use is also commonly assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

How are the predictors weighted in the Technology Acceptance Model?

Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use do not always contribute equally to predicting intentions. Sometimes, an individual’s intentions may be determined largely by perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use may have little or no influence. Other times, perceived ease of use may exert more influence. For example, college students’ perceived usefulness to use online therapy may largely be driven by their perceptions that online therapy is useful; whether or not they perceive it is easy to use may not influence their intentions as strongly. This information is important, because it can help persuaders strategically design messages to motivate people to adopt a particular behavior. The only way to determine the relative importance (or weighting) of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use on intentions is to measure these variables across a group of study participants and run a statistical analysis.

What influences the relationship between intentions and behavior?

The Technology Acceptance Model predicts that intentions lead to behavior; however, intentions do not always guarantee behavior. For example, someone might intend to use online therapy but not follow through. There are several factors that influence the strength of the relationship between intentions and behavior.

First, the Technology Acceptance Model is derived from the Theory of Reasoned Action (see Chapters 4 and 5), which underscores a principle of specificity. This means that in order to best predict behavior, the perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use must relate to specific intentions and a subsequent specific behavior. These frameworks note that any given behavior includes an action, target, context and time period. For example, a goal might be “to use online therapy for one session per week in the upcoming month.” In this example, “use online therapy” is the action, “one session” is the target, “each week” is the context, and “in the upcoming month” is the time period. As the specificity of the behavior increases, intentions become a better predictor of behavior.

Additionally, the temporal stability of intentions influences the strength of the relationship between intentions and behavior. If an individual’s intentions fluctuate over time (e.g., some days I intend to use online therapy, and other days I do not), then intentions measured at one particular time might not predict subsequent behavior (e.g., Rhodes & Dickau, 2013). As the stability of an individual’s intentions increases over time, intentions become a better predictor of behavior.

What additional predictors have been examined in the Technology Acceptance Model?

In it’s application, The Technology Acceptance Model has seen theoretical expansions to include several other predictor variables in addition to perceived usefulness and ease of use. One of the expansions is the inclusion of perceived risk (Pavlou, 2003). Perceived risk of a technology has been defined as the degree to which an individual believes that using the technology involves exposure to danger (see Schnall, Bakken, Rojas, Travers, & Carballo-Dieguez, 2015). In the Technology Acceptance Model, as perceived risk increases, intentions to use the specific technology decreases.

The Technology Acceptance Model has also been expanded to include perceived trust (Pavlou, 2003), and a meta-analysis found that perceived trust does improve the predictive ability of the Technology Acceptance Model (Wu, Zhao, Zhu, Tan, & Zheng, 2011). Perceived trust of a technology has been defined as the degree to which an individual believes that the other party will act responsibly and will not attempt to exploit the user (see Schnall et al., 2015). In the Technology Acceptance Model, as perceived trust increases, intentions to use the specific technology also increase.

Subjective norms have also been added as a predictor of intentions to use a specific technology (Legris, Ingham, & Collerette, 2003), and a meta-analysis found that subjective norms do improve the predictive ability of the Technology Acceptance Model (Schepers & Wetzels, 2007). Subjective norms are defined as the degree to which an individual believes that important others think they ought to perform a behavior. In the Technology Acceptance Model, as subjective norms increase, intentions to use the specific technology also increase.

How can the Technology Acceptance Model be used to create persuasive messages?

The Technology Acceptance Model specifies that it is possible to change someone’s intentions to use a technology by influencing one or more of the predictors of intentions. The Technology Acceptance Model itself does not specify the beliefs that comprise perceived usefulness and ease of use nor does it identify strategies to shift these variables in the desired direction. This chapter therefore incorporates and adapts information from the Theory of Planned Behavior (see Chapters 4 & 5) to provide some useful suggestions.

Perceived Usefulness

As mentioned, perceived usefulness is defined as the degree to which an individual believes that using a particular technology would be beneficial. Perceived usefulness may be a function of an individual’s evaluation of a belief about usefulness and the strength of that belief. For example, the strength of a belief about usefulness could be associated with the following questionnaire:

The evaluation of each belief about usefulness could be assessed with the following questionnaire:

Changing an individual’s perceived usefulness could therefore be achieved by changing the strength of an existing salient belief. This might involve increasing the salience of an existing positive belief (e.g., “You might think that online therapy would reduce your depression, but you might not realize just how useful it can really be”).

Changing an individual’s perceived usefulness could also be achieved by changing the evaluation of an existing salient belief. This might involve increasing the salience of an existing positive belief (e.g., “You might think that reducing your depression can be beneficial, but you might not realize just how much of a positive impact it can have”).

Perceived Ease of Use

Changing an individual’s perceptions that the specific technology is easy to use can be accomplished in many ways. The persuader could directly remove the obstacle, create the opportunity for successful use of the technology (e.g., “I’ve done it before, so I can do it again”), provide examples of others who have successfully used the technology (e.g., “If it is easy for them, it will be easy for me”), or provide verbal encouragement (e.g., “You can do it!”; O’Keefe, 2016). Any of these strategies individually, or concurrently, positively influence an individual’s perceptions that using a particular technology would be easy.

References

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 319-340.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982-1003.

Kamal, S. A., Shafiq, M., & Kakria, P. (2020). Investigating acceptance of telemedicine services through an extended technology acceptance model (TAM). Technology in Society, 60, 101212.

Legris, P., Ingham, J., & Collerette, P. (2003). Why do people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model. Information & Management, 40(3), 191-204.

Min, S., So, K. K. F., & Jeong, M. (2019). Consumer adoption of the Uber mobile application: Insights from diffusion of innovation theory and technology acceptance model. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(7), 770-783.

O’Keefe, D. J. (2016). Persuasion: Theory and Research (Third Edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust and risk with the technology acceptance model. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 7(3), 101-134.

Schepers, J., & Wetzels, M. (2007). A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model: Investigating subjective norm and moderation effects. Information & Management, 44(1), 90-103.

Scherer, R., Siddiq, F., & Tondeur, J. (2019). The technology acceptance model (TAM): A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach to explaining teachers’ adoption of digital technology in education. Computers & Education, 128, 13-35.

Schnall, R., Bakken, S., Rojas, M., Travers, J., & Carballo-Dieguez, A. (2015). mHealth technology as a persuasive tool for treatment, care and management of persons living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 19(2), 81-89.

Sukendro, S., Habibi, A., Khaeruddin, K., Indrayana, B., Syahruddin, S., Makadada, F. A., & Hakim, H. (2020). Using an extended Technology Acceptance Model to understand students’ use of e-learning during Covid-19: Indonesian sport science education context. Heliyon, 6(11), e05410.

Worthington, A. K., Burke, E. E., Shirazi, T. N., & Leahy, C. (2020). US women’s perceptions and acceptance of new reproductive health technologies. Women’s Health Reports, 1(1), 402-412.

Wu, K., Zhao, Y., Zhu, Q., Tan, X., & Zheng, H. (2011). A meta-analysis of the impact of trust on technology acceptance model: Investigation of moderating influence of subject and context type. International Journal of Information Management, 31(6), 572-581.