12 Hope Appeals: Persuasive Hope Theory

Amber K. Worthington

Acknowledgements: The examples used in this chapter were provided by Jordan Q. Ahgeak. The examples were adapted for use in this chapter by the author.

Hope has the potential to persuade people to adopt various behaviors. Indeed, hope is a discrete, future-oriented emotion that can motivate people’s behavior by focusing their thoughts on opportunities to achieve future rewards (Chadwick, 2015).

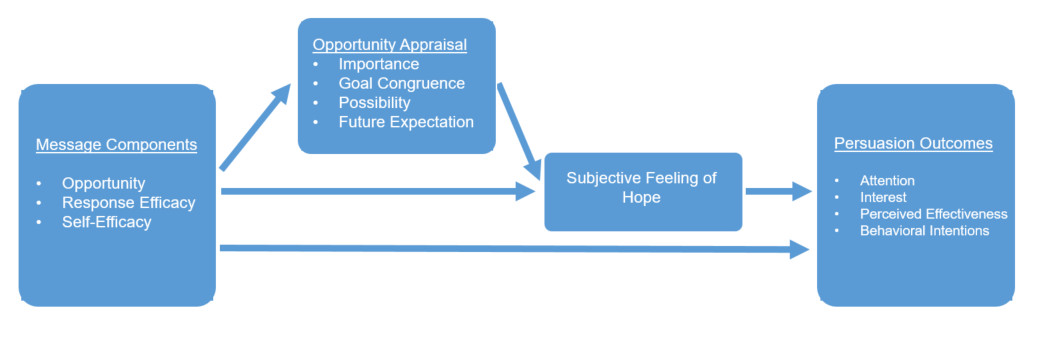

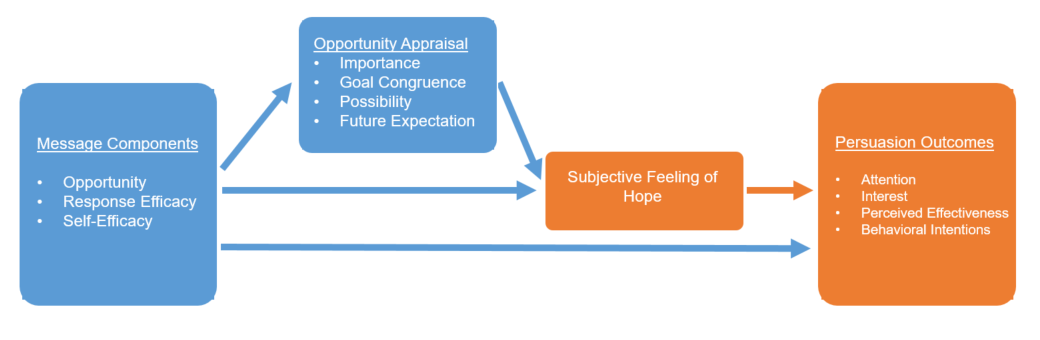

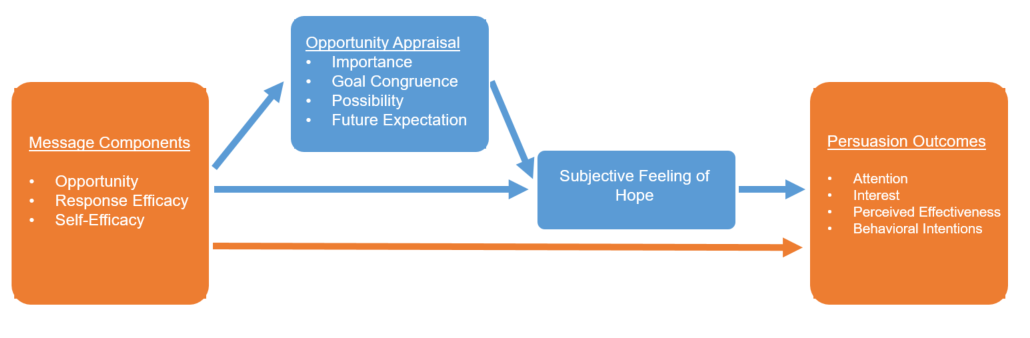

A hope appeal is a message strategy that attempts to persuade people to adopt a specific action by arousing hope. Hope appeals are a relatively recent addition to the study of persuasion (see Chadwick, 2010), and this chapter focuses on Persuasive Hope Theory (Chadwick, 2015). Persuasive Hope Theory defines hope and describes the message features needed for an effective hope appeal. The image below depicts Persuasive Hope Theory:

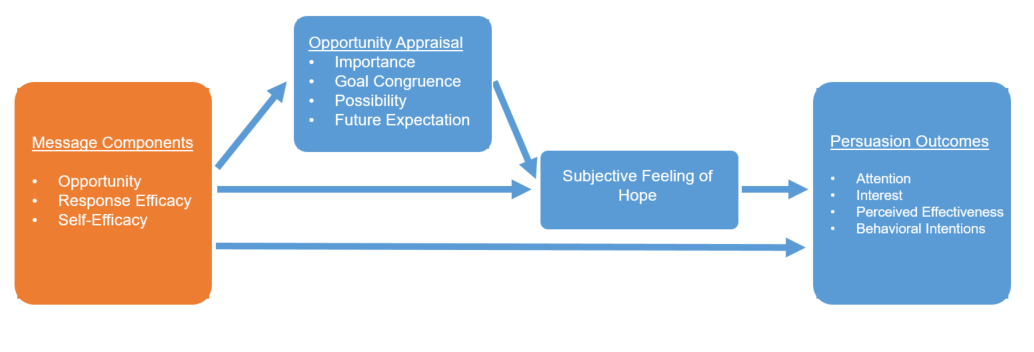

Persuasive Hope Theory begins with a hope appeal message, which includes message content related to a specific opportunity and the efficacy of a specific recommended behavior to achieve a desired outcome. This part of the theory is highlighted in the figure below:

For example, Jordan Q. Ahgeak (see Acknowledgements) noted that one opportunity in Alaska might be to reduce light pollution in Utqiaġvik (also known as Barrow), and a specific recommended behavior to achieve that outcome might be to lessen the amount of insignificant artificial lighting (for example, turning off porch lights and turning off lights of unoccupied buildings/offices). Here is an example message:

According to Persuasive Hope Theory, the first thing someone does when reading the message is to appraise the opportunity. This includes assessing the opportunity using perceptions of importance, goal congruence, possibility, and future expectation. In the above example, this would be whether or not someone reading the message perceives that reducing light pollution in Utqiaġvik is important, congruent with their goals, possible, and would lead to a better future.

Perceived importance includes an assessment of whether the future outcome is personally relevant. Perceived goal congruence refers to whether the future outcome is consistent with and favorable to their personal goals or motives. Perceived possibility includes an assessment of the likelihood of the future outcome, and perceived future expectation refers to whether the outcome would lead to a better future.

The message component designed to lead to appraisals of importance and goal congruence connects reducing light pollution to preserving “the beauty of the night sky” and showing “respect for nature.” This was done because Jordan Ahgeak noted that her Utqiaġvik community follows a traditional set of twelve values: Avoidance of Conflict, Compassion, Cooperation, Family and Kinship, Humility, Humor, Hunting Traditions, Knowledge of our Language, Love and Respect for our Elders and One Another, Respect for Nature, Sharing, and Spirituality. The community members have learned, taught, and incorporated these values throughout their lives and subsistence living, thus underscoring the personal relevance and importance of respecting nature for a message recipient from Utqiaġvik. The possibility and future expectation message components indicate that it is likely that the message recipient can help improve the situation, which would make the future better.

When reading this message, someone in the contiguous United States (or Lower 48) might believe that preserving the beauty of the night sky in Utqiaġvik is possible, but they might not believe that this outcome is personally important to them, is congruent with their goals, or that it would lead to a better future. A community member in Utqiaġvik, on the other hand, might perceive that preserving the beauty of the night sky is important, congruent with their personal goals, possible, and would lead to a better future.

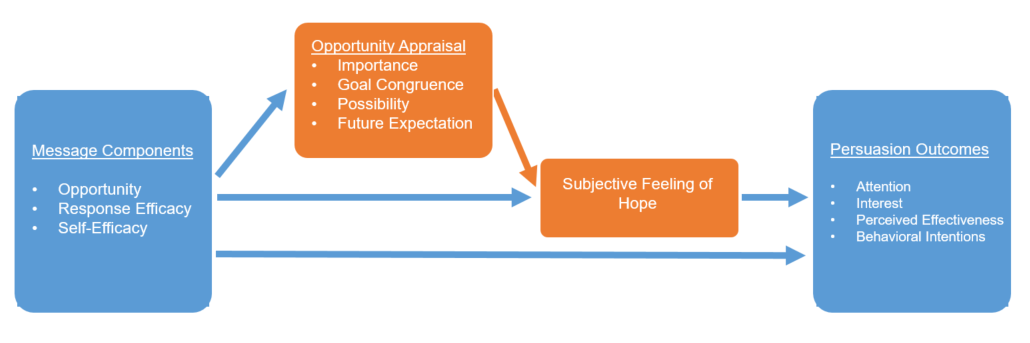

If someone perceives the opportunity as low (i.e., if the person does not believe the opportunity is important, goal congruent, possible, and/or would lead to a better future) then they will not feel hope. If someone perceives the opportunity as high (i.e., if the person does believe the opportunity is important, goal congruent, possible, and would lead to a better future) then they will feel hope. This part of the theory is highlighted in the figure below:

The next thing someone will do when reading the message is appraise the efficacy. This includes assessing whether they believe that the recommended behavior will help them achieve the desired outcome, which is referred to as response efficacy, and whether they believe they are capable of doing the recommended behavior, which is referred to as self-efficacy.

In the above example, this would be whether or not someone reading the message perceives that the recommended behavior to “turn off porch lights and lights in unoccupied buildings” would help reduce light pollution (i.e., response efficacy) and whether they believe they are capable of turning off those lights (i.e., self-efficacy).

For example, someone might believe that turning off porch lights would not help reduce light pollution (i.e., low response efficacy) even if they think they could turn off their porch lights (i.e., high self-efficacy). Someone else might think that turning off their porch lights would help reduce light pollution (i.e., high response efficacy) and might also think they are capable of doing that (i.e., high self-efficacy).

If someone perceives the efficacy as low (i.e., low response efficacy and/or low self-efficacy) then they will not feel hope. If someone perceives the efficacy as high (i.e., high response efficacy and high self-efficacy), then they will feel hope. This part of the theory is highlighted in the figure below:

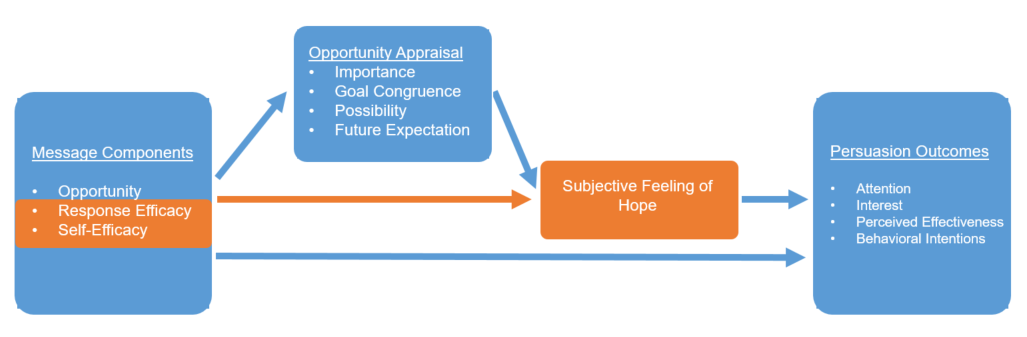

Persuasive Hope Theory states that this subjective feeling of hope can lead to several different persuasion outcomes, including attention, interest, perceived effectiveness, and behavioral intentions. Indeed, Chadwick (2015) notes that the focused, eager feeling of hope should increase general attention to the message, general interest in the topic, perceptions that the message is effective, and intentions to engage in the recommended behavior. Additional research is needed to refine this part of the theory, but some previous research and empirical work support this. This part of the theory is highlighted in the figure below:

Persuasive Hope Theory also notes that the message components themselves can lead directly to the above mentioned persuasion outcomes. This means that when a message specifically states that the future outcome is important, congruent with goals, possible, and would lead to a better future, this can lead directly to an increase in general attention to the message, general interest in the topic, perceptions that the message is effective, and intentions to engage in the recommended behavior. This part of the theory is highlighted in the figure below:

This is a relatively new theory in persuasion, and therefore additional research is needed to establish all of these theoretical claims.

What influences the relationship between attention, interest, perceived effectiveness, behavioral intentions, and behavior change?

Persuasive Hope Theory states that a hope message can lead to increased attention, interest, perceived effectiveness, and behavioral intentions. However, in persuasion, we are also interested in changing behaviors themselves.

Similar to the Theory of Planned Behavior (Chapters 4 & 5) and the Technology Acceptance Model (Chapters 6 & 7), the persuasion outcomes in Persuasive Hope Theory do not always guarantee behavior change. For example, someone might pay attention to the message, think it is interesting, and intend to turn their porch lights off but not follow through. There are several factors that influence the strength of the relationship between attention, interest, perceived effectiveness, behavioral intentions, and behavior change.

First, in order to best predict behavior change, the beliefs must relate to specific intentions and a subsequent specific behavior. Any given behavior can include an action, target, context and time period. For example, a goal might be “turning off porch lights every night when I’m back home during winter.” In this example, “turning off porch lights” is the action, “every night” is the target, “when I’m back home” is the context, and “during winter” is the time period. As the specificity of the behavior increases, the persuasion outcomes in Persuasive Hope Theory become a better predictor of behavior change.

Additionally, the temporal stability of attention, interest, perceived effectiveness, and behavioral intentions influences the strength of the relationship between these persuasion outcomes and behavior. If an individual’s feeling of hope and therefore, for example, interest fluctuates over time (e.g., some days I perceive a high opportunity to reduce light pollution and other days I do not), then persuasion outcomes measured at one particular time might not predict subsequent behavior change (e.g., Rhodes & Dickau, 2013). As the stability of an individual’s persuasion outcomes increases over time, message acceptance becomes a better predictor of behavior.

How can Persuasive Hope Theory be used to create persuasive messages?

Persuasive Hope Theory specifies that it is possible to change someone’s behavior by influencing their perceived opportunity (i.e., perceived importance, goal congruence, possibility, and future expectation) and perceived efficacy (i.e., response efficacy and self-efficacy).

Importance

Chadwick (2010) notes several message strategies that could be used to increase a message reader’s perceived importance. For example, the message can use the second person (e.g., “you”) and focus specifically on how the recommended behavior would affect the reader. For example, a message on climate change manipulated to have high importance could include: “The climate affects your well-being in many ways. Protecting the climate is VERY important for your well-being” (see Chadwick, 2010).

Goal Congruence

There are also message strategies that could be used to increase a message reader’s perceived goal congruence (Chadwick, 2010). For example, the message can again use the second person (e.g., “you”) and focus specifically on how the opportunity impacts the reader’s goals (which may require some background research). Chadwick (2010) found that saving money is an important goal for undergraduate students, and therefore used this background research to construct an example message on climate change that was manipulated to have high goal congruence: “Protecting the climate saves you a lot of money. You can make simple changes to protect the climate. You can use less energy, use less hot water, and make less trash. These changes are free or cheap. These small changes will directly save you at least $500 per year. Protecting the climate saves you In four years at Penn State, you will save $2000! That is a lot of money.”

Possibility

A message reader’s perceptions of possibility could be created by several message strategies. Chadwick (2010) notes that a message should use the second person (e.g., “we”) and should state that it is possible for the message reader to help create a better future. Modifiers like “very” can also be used. Here is an example message on climate change that was manipulated to have high possibility: “It is very likely that we can make the climate better. All over the world, people like you are taking action. They are using less energy, using less hot water, and making less trash. Billions of people are taking action to protect the climate. You can join the effort and make it even more likely that we will make the climate better” (Chadwick, 2010).

Future Expectation

Chadwick (2010) also discusses several ways to increase a message reader’s perceptions of future expectation. Again, the second person (e.g., “you”) should be used, and the message should explicitly say how much better the future will be. Additional modifiers like “many” and “much” can be added for emphasis. Here is an example message related to climate change that has high future expectation: “Protecting the climate will make the future much better. Protecting our climate will bring a wonderful future. Our air will be much cleaner. Our weather will be much less extreme. Our summers will be beautiful and mild. We will experience many fewer diseases and will live much longer. Growing food will be easier and more productive. Protecting the climate will have By helping protect the climate, you can help create a wonderful future” (Chadwick, 2010)

Response Efficacy

There are some message strategies that could be used to increase a message reader’s perceived response efficacy. For example, the message could provide examples of when the recommended behavior has previously effectively achieved the desired future outcome (e.g., “This has worked in the past!”) or explicitly state ways that the recommended behavior will lead to the desired future outcome.

Self-Efficacy

Various message strategies could be used to increase a message reader’s perceived self-efficacy. For example, the message could provide examples of others who have successfully performed the behavior (e.g., “If they can do it, I can do it”), provide verbal encouragement (e.g., “You can do it!”; O’Keefe, 2016), or explicitly state that the recommended behavior is affordable, easy to implement, and so on. Any of these strategies individually, or concurrently, could influence a person’s perceptions of self-efficacy.

References

Chadwick, A. E. (2010). Persuasive hope theory and hope appeals in messages about climate change mitigation and seasonal influenza prevention. Doctoral Dissertation. The Pennsylvania State University.

Chadwick, A. E. (2015). Toward a theory of persuasive hope: Effects of cognitive appraisals, hope appeals, and hope in the context of climate change. Health Communication, 30(6), 598-611.

O’Keefe, D. J. (2015). Persuasion: Theory and research (Third edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.