10 Fear Appeals: The Extended Parallel Process Model

Amber K. Worthington

How many times have you come across a message that tries to scare people into doing something? For example, messages may attempt to use fear to persuade people to stop smoking, refrain from drinking alcohol and driving, wear a helmet, and so on.

Importantly, messages that use fear are not always effective, and communication theories can be used to help explain when these fear appeals likely will or will not work. This chapter reviews fear appeals and explains how to create effective fear appeal messages.

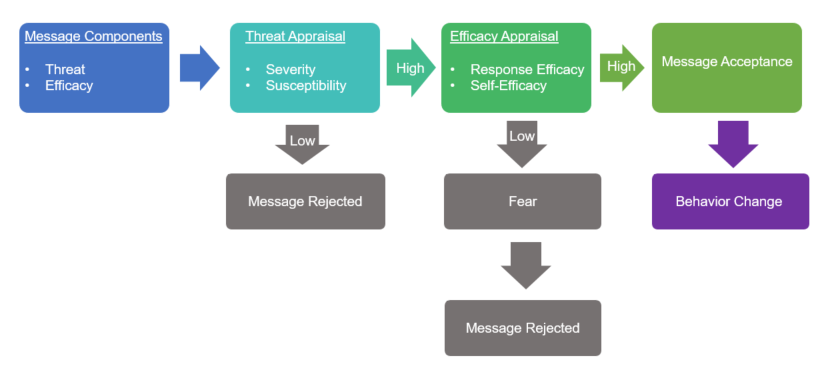

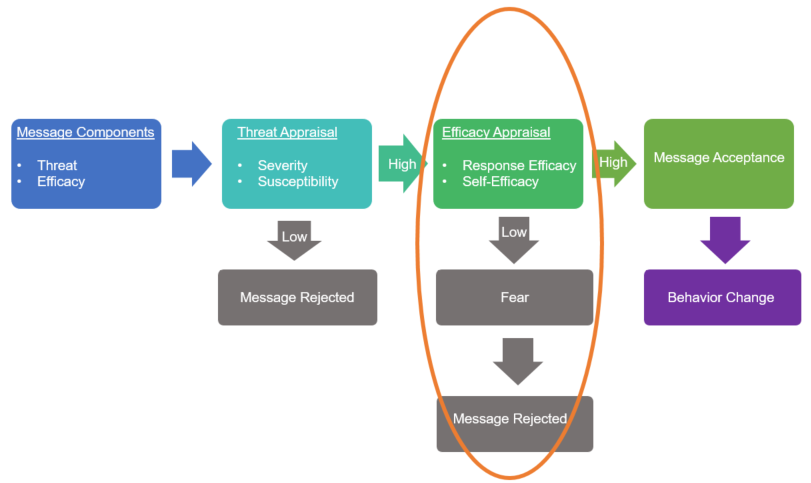

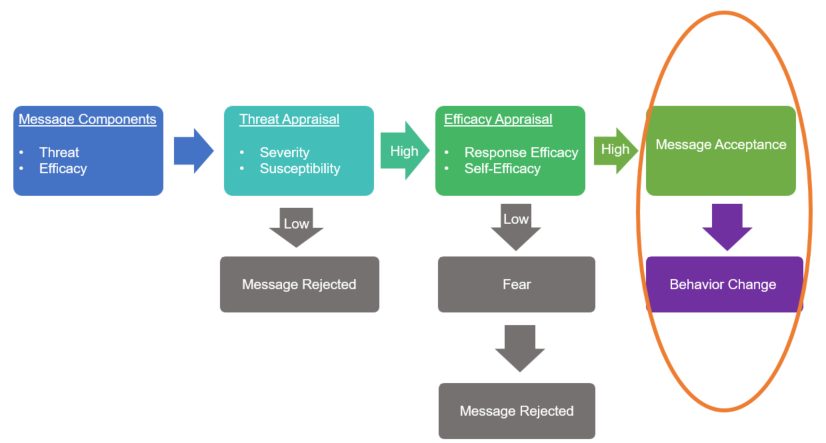

A fear appeal is a message strategy that attempts to persuade people to adopt a specific action by arousing fear. Fear appeals have a long history, including Levanthal’s (1970, 1971) parallel process model and Roger’s (1975, 1983) protection motivation theory. This chapter focuses on the most frequently used fear appeal theory today, which is Witte’s (1992) Extended Parallel Process Model. The Extended Parallel Process Model describes when a message with fear will be effective and when it will not. The image below depicts the Extended Parallel Process Model:

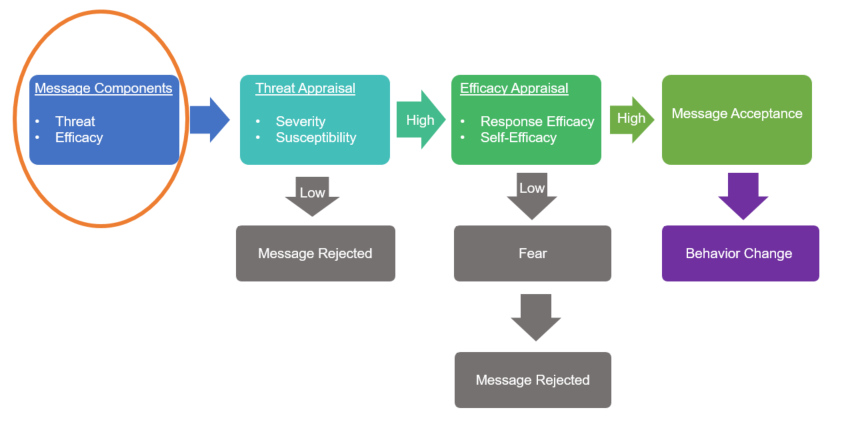

The Extended Parallel Process Model begins with a fear appeal message, which includes message content related to a specific threat and the efficacy of a specific recommended behavior to resolve that threat. This part of the model is highlighted in the figure below:

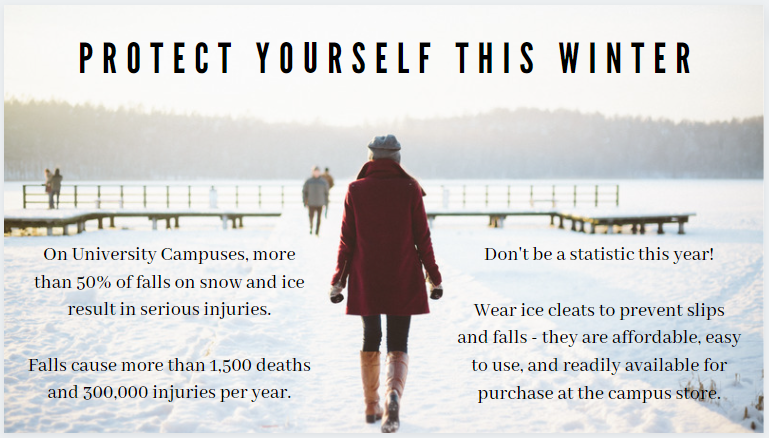

For example, a threat might be icy sidewalks on a university campus, and a specific recommended behavior to resolve that threat might be to wear ice cleats. Here is an example message:

According to the Extended Parallel Process Model, the first thing someone does when reading the message is to appraise the threat. This includes assessing whether they perceive that the threat is severe, which refers to their perception of the magnitude of the threat (i.e., perceived severity), and whether they perceive that they are susceptible to the threat, which refers to their perception of the likelihood that the threat will impact them (i.e., perceived susceptibility).

In the above example, this would be whether or not someone reading the message perceives that falls on snow and ice are severe (e.g., “Falls cause more than 1,500 deaths and 300,000 injuries per year”) and whether or not they perceive that they are susceptible to falling on snow and ice (e.g., “On University Campuses”). For example, a student in Florida might perceive that falling on snow and ice is severe, but they might not believe they are susceptible to falling on snow and ice on their Florida campus. A student in Alaska, on the other hand, might perceive that falling on snow and ice is severe and that they are susceptible to it on their Alaska campus.

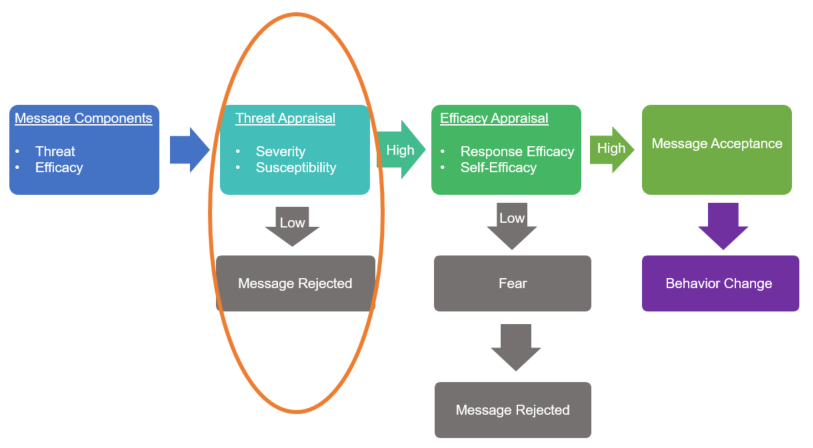

If someone perceives the threat as low (i.e., if the person does not believe the threat is severe and/or does not believe they are susceptible to the threat) then they will reject the message. This part of the model is highlighted in the figure below:

If someone perceives the threat as high (i.e., if the person believes the threat is severe and that they are susceptible to it) then they will keep reading the message. The next thing they will do is appraise the efficacy. This includes assessing whether they believe that the recommended behavior will prevent or reduce the threat, which is referred to as response efficacy, and whether they believe they are capable of doing the recommended behavior, which is referred to as self-efficacy.

In the above example, this would be whether or not someone reading the message perceives that the recommended behavior to wear ice cleats would prevent a fall on ice (i.e., response efficacy) and whether they believe they are capable of affording, using, and finding ice cleats (i.e., self-efficacy). For example, someone might believe that ice cleats would work to prevent falls (i.e., high response efficacy) but might also think they would not be able to afford them (i.e., low self-efficacy). Someone else might think that ice cleats would work to prevent falls (i.e., high response efficacy) and might also think they could afford to purchase them (i.e., high self-efficacy).

If someone perceives the efficacy as low (i.e., if the person does not believe that the recommended behavior would prevent the threat and/or does not believe they are capable of enacting the recommended behavior) then they will reject the message. This part of the model is highlighted in the figure below:

If someone perceives the efficacy as high (i.e., they have both high response efficacy and self-efficacy), they will accept the message. According to the Extended Parallel Process Model, someone who accepts the message is then likely to change their behavior accordingly. This part of the model is highlighted in the figure below:

What influences the relationship between message acceptance and behavior change?

The Extended Parallel Process Model states that message acceptance leads to behavior change; however, similar to the Theory of Planned Behavior (Chapters 4 & 5) and the Technology Acceptance Model (Chapters 6 & 7), message acceptance does not always guarantee behavior change. For example, someone might accept the message and intend to buy and use ice cleats but not follow through. There are several factors that influence the strength of the relationship between message acceptance and behavior change.

First, in order to best predict behavior change, the message acceptance beliefs must relate to specific intentions and a subsequent specific behavior. Any given behavior can include an action, target, context and time period. For example, a goal might be “to use ice cleats every time when walking outside during winter.” In this example, “using ice cleats” is the action, “every time” is the target, “when walking outside” is the context, and “during winter” is the time period. As the specificity of the behavior increases, message acceptance becomes a better predictor of behavior change.

Additionally, the temporal stability of message acceptance influences the strength of the relationship between message acceptance and behavior. If an individual’s message acceptance fluctuates over time (e.g., some days I perceive the threat of falling to be high and other days I do not), then message acceptance measured at one particular time might not predict subsequent behavior change (e.g., Rhodes & Dickau, 2013). As the stability of an individual’s message acceptance increases over time, message acceptance becomes a better predictor of behavior.

When is it appropriate to use fear in persuasive messages?

Fear can be an effective persuasive tool when following the Extended Parallel Process Model. Very importantly, however, there are certain conditions where fear may be appropriate and other conditions where fear may be inappropriate or even unethical. Indeed, Peters, Ruiter, and Kok (2013) note that high feelings of threat when coupled with low efficacy can cause people to engage in health-defeating behaviors. Thus, using fear only works when the population has a high baseline efficacy or when the message also includes powerful information to enhance efficacy (Peters et al., 2013). Together, this suggests that fear is only appropriate when the message recipients have high response and self-efficacy regarding the recommended behavior or when it is possible to strongly increase their response and self-efficacy with the message. When efficacy is low, other persuasive tools should be used (e.g., see Chapters 12 & 13 on Hope Appeals).

How can the Extended Parallel Process Model be used to create persuasive messages?

The Extended Parallel Process Model specifies that it is possible to change someone’s behavior by influencing their perceived threat (i.e., perceived severity and perceived susceptibility) and perceived efficacy (i.e., response efficacy and self-efficacy).

Perceived Severity

The Extended Parallel Process Models notes that vivid language can be used to increase perceptions that a specific health threat is severe. Vivid language and descriptions to increase perceptions of severity include specific references to the severity of the threat (e.g., the magnitude of harm) and the terrible consequences of a health threat (Witte & Allen, 2000). Witte (1992) also stated gruesome symptom descriptions are a form of vivid language. Examples ranged from neutral language (“the patient complained of fatigue and a rash”) to moderately vivid language (“the patient complained of fatigue and lumps on the neck”) to extremely vivid language (“the patient complained of fatigue and bleeding, oozing sores all over his body”; Witte, 1994, p. 120).

Perceived Susceptibility

The Extended Parallel Process Models states that personalistic language or imagery can be used to increase perceptions that someone is susceptible to a specific health threat. Personalistic language and descriptions can include references to the target population’s susceptibility to the specific health threat (e.g., their likelihood of experiencing the negative consequences of the threat; Witte & Allen, 2000). Personalistic language could also emphasize the similarities between people impacted by the health threat and the target audience (e.g., “You face a 40% chance of facing these consequences”; see Witte & Allen, 2000).

Response Efficacy

There are some message strategies that could be used to increase a message reader’s perceived response efficacy. For example, the message could provide examples of when the recommended behavior has previously effectively prevented the threat (e.g., “This has worked in the past!”) or explicitly state ways that the recommended behavior will prevent the threat.

Self-Efficacy

Various message strategies could be used to increase a message reader’s perceived self-efficacy. For example, the message could provide examples of others who have successfully performed the behavior (e.g., “If they can do it, I can do it”), provide verbal encouragement (e.g., “You can do it!”; O’Keefe, 2016), or explicitly state that the recommended behavior is affordable, easy to implement, and so on. Any of these strategies individually, or concurrently, could influence a person’s perceptions of self-efficacy.

References

Levanthal, H. (1970). Findings and theory in the study of fear communications. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 5, pp. 119-186). New York: Academic Press.

Levanthal, H. (1971). Fear appeals and persuasion: The differentiation of a motivational construct. American Journal of Pubic Health, 61, 1208-1224.

O’Keefe, D. J. (2015). Persuasion: Theory and research (Third edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Peters, G. J. Y., Ruiter, R. A., & Kok, G. (2013). Threatening communication: a critical re-analysis and a revised meta-analytic test of fear appeal theory. Health Psychology Review, 7(sup1), S8-S31.

Rhodes, R. E., & Dickau, L. (2013). Moderators of the intention-behaviour relationship in the physical activity domain: a systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(4), 215-225.

Rogers, R. W. (1975). A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. Journal of Psychology, 91, 93-114.

Rogers, R. W. (1983). Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. In J. Cacioppo & R. Petty (Eds.), Social Psychophysiology (pp. 153-176). New York: Guillford.

Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 59, 329-349.

Witte, K. (1994). Fear control and danger control: A test of the extended parallel process model (EPPM). Communication Monographs, 61, 113-134.

Witte, K., & Allen, M. (2000). A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior, 27(5). 591-615.