2 Communication Foundations

Communication can mean different things to different people. It is impacted and influenced by our experiences, perceptions, culture, and more.

There are many current models and theories that help explain, plan, and predict communication processes and their successes or failures. In the workplace, we might be more focused on the specific skills and techniques that can be used in day-to-day workplace writing more than theory. However, good practice is built on a solid foundation of “the big picture” that exists surrounding communication.

How does communication work as a process? How should people communicate with each other? What is expected of communicators in today’s workplaces? What cultural and interpersonal communication information do you need to thrive?

The Communication Process

Every day, we receive messages, either in text or spoken form, that make us feel something. Maybe it made you excited or annoyed, happy or sad. But what specifically made you feel that way? Could you specifically articulate why the message made you respond in the way you did? This is where MacLennan’s (2009) Nine Axioms of Communication come in. They can help us understand how communication works and and help us identify effective communication strategies and diagnose problems. MacLennan defines an axiom. In other words, the axioms of communication are inescapable principles that we must always strive to be conscious of, no matter what type of communication we are engaging in. Here all nine axioms listed out.

The Nine Axioms of Communication

- Communication is not simply an exchange of information, but an interaction between people.

- All communication involves an element of relation as well as content.

- Communication takes place within a context of “persons, objects, events, and relations.”

- Communication is the principal way by which we establish ourselves and maintain credibility.

- Communication is the main means through which we exert influence.

- All communication involves an element of interpersonal risk.

- Communication is frequently ambiguous: what is unsaid can be as important as what is said.

- Effective communication is audience-centered (or reader-centered), not self-centered (or writer-centered).

- Communication is pervasive: you cannot not communicate.

(MacLennan, 2009)

These axioms help you design effective messages so that you better understand what you should say and how you should say it. Just as importantly, the axioms tell you what you should not say and what you should avoid when designing and delivering a message.

Bear in mind that while each axiom emphasizes a specific aspect of communication, the axioms are interconnected; therefore, attempting to ignore or downplay the importance of any of them can impair your ability to communicate effectively.

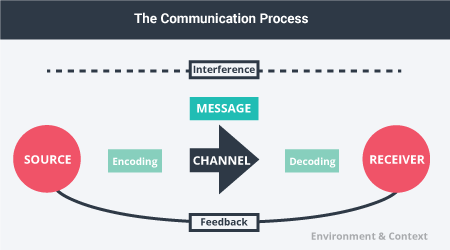

When we talk about communication, we also often try to explain it visually through a model. In the model shown in Figure 1 communication is shown in terms of how messages are transmitted.

Fig. 1 The communication process by Laura Underwood

In this linear model, a source encodes information and, through a transmitter, sends it to a receiver, who subsequently decodes the message. Information looks like it moves in a simplified, linear manner, but if you look closely the process can be complicated by interference, which is information that is added unintentionally to a message during transmission, and feedback, which is information that the receiver transmits back to the sender, sometimes without even realizing they are doing so.

The first rule of communication is to know your audience and put them first. You can use this model and the nine axioms to think about how to best encode your messages for them and and how to send it to them. You can also think about what types of interference (noise) could prevent your message from being received, understood, or accepted. Finally, you can think about what feedback you’ll look for when determining if your message was successful.

How Should People Communicate With Each Other?

Clearly. Honestly. Transparently. Patiently. Thoughtfully. Fairly. Positively. Interactively. Respectfully. Ethically.

All of those are good answers; this section is focused on the last one: ethical communication.

Every one of us is responsible for how we communicate and what we communicate. This responsibility can be interpersonal, managerial, or even legal. Audiences have high expectations regarding ethical communication (even if they aren’t always the most ethical communicators themselves).

Ethical communication

When you are communicating in a professional workplace, there’s a strong expectation that you’ll communicate ethically. There are a few core issues you’ll need to understand, such as privacy, confidentiality, and the duty to communicate.

CONFIDENTIALITY Information is owned. The owner of that information gets to decide what to do with it. If you have information that is rightfully owned by somebody else, you need to know if that information is confidential (or perhaps merely private). Virtually all organizations have confidential documents, especially employee records, legal documents, and certain financial documents. If you’re receiving confidential information, you have a duty to safeguard that information. Revealing confidential information, even accidentally, is unethical and can have serious repercussions, including legal consequences.

PRIVACY Some information may not be confidential, per se, but it is nonetheless private. In a free democracy, voters are allowed to vote in private so that nobody can see how they marked their ballot. Ballots have no identifying marks to show how any particular person voted, but the tallies of votes are public information. If somebody tells you that they voted a particular way, that’s not confidential information, but it was kept private (until the voter voluntarily chose to disclose the information). In a business setting, a lot of communication takes place in private, often even when it is not confidential. Violating the privacy of communications can also have terrible consequences, though, and is seen as unethical.

DUTY TO COMMUNICATE In some situations, you have an ethical and/or legal duty to communicate. If you are an accountant auditing the finances of another company and you detect irregularities in that company’s records, you have a duty to report the matter. If you are a local government and you want to collect the annual tax roll, you have a duty to communicate the tax rate to residents.

Every industry and profession has its own set of communication responsibilities. Ethical communication relies on you knowing your obligations to various stakeholders and meeting them.

What Cultural Communication Information Do I Need to Thrive?

Culture involves beliefs, attitudes, values, and traditions that are shared by a group of people. From the choice of words (message), to how you communicate (in person, in print, digitally, or otherwise), to how you acknowledge understanding with a nod or a glance (non-verbal feedback), to the internal and external interference, all aspects of communication are influenced by culture.

Culture is part of the very fabric of our thought and you cannot separate yourself from it, even as you leave home, or defining yourself professionally at work. Every business or organization has a culture and, within what may be considered a global culture, there are many subcultures or co-cultures. For example, consider the difference between the sales and accounting departments in a corporation. You can quickly see two distinct groups with their own symbols, vocabulary, and values. Within each group, there may also be smaller groups and each member of each department comes from a distinct background that, in itself, influences behavior and interaction.

Intercultural communication is a fascinating area of study within business communication and it is essential to your success. One idea to keep in mind as you examine this topic is the importance of considering multiple points of view. If you tend to dismiss ideas or views that are “unalike culturally,” you will be less able to learn about diverse cultures. If you cannot learn, how can you grow and be successful?

Through intercultural communication, we create, understand, and transform culture and identity. One reason you should study intercultural communication is to foster greater self-awareness (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). Your thought process regarding culture is often “other focused,” meaning that the culture of the other person or group is what stands out in your perception. Intercultural communication can allow you to step outside of your comfortable, usual frame of reference and see your culture through a different lens. Additionally, as you become more self-aware, you may also become a more ethical communicator.

How Should People Communicate With Each Other?

Interpersonal communication is complex and dependent on so many variables, such as those discussed above. The changing social, political, religious, sexual, artistic, and economic conditions of our world, country, region, and even organizations need to be accounted for. Recent communication adaptations include sharing one’s pronouns and making land acknowledgments.

As professional communicators, we should use respectful, appropriate, and non-judgmental language to ensure that we communicate clearly, respectfully, and ethically. Pay close attention to the issues that arise in politics and society around communication; learning opportunities abound and learning the easy way is much better than learning the hard way, which can involve a lot of unpleasantness for everyone involved.

References

Martin, J. N., and Thomas K. N., Intercultural Communication in Contexts, 5th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2010).

McLean, S. (2005). The basics of interpersonal communication. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Attribution

This chapter partly adapted from Part 1 (Foundations) in the Professional Communications OER by the Olds College OER Development Team and is used under a CC-BY 4.0 International license.

a universal principle of foundational truth that operates across cases or situations

a person who sends a message

a person for whom the message is intended

information that is unintentionally added to a message or that confuses or disrupts a message during transmission, also known as "noise"

information sent back to the sender

a formal statement that one works or that an event is taking place on land originally inhabited by indigenous peoples