36 The Descriptive Writer’s Toolbox

Greg Hartley

Did you notice the problem with this “description”? To some, it may seem perfectly acceptable. But ask yourself: after reading that passage, did you get a clear picture of what the student actually saw? Was the image in your head likely to match the image the student remembered? In both cases, the answer, sadly, is no. We can sense the sincerity and detect that the writer was moved by the scene, but the description fails to share their vision with the reader. So what went wrong?

Beginning writers make two major mistakes in their first attempts to write descriptions. They use subjective words and neglect vivid details. Let’s briefly examine both of these.

Notice the bold-print words in the student’s example above: beautiful, wonderful, gorgeous, lucky, and lovely. These words are subjective. The precise definition of a subjective word will shift from user to user. What is my ugly won’t be your ugly. What is my beautiful won’t be yours either. So if I label an object as wonderful, I am simply declaring that an object meets my subjective criteria without sharing what those criteria are. I am withholding information instead of revealing it. That’s the opposite goal of effective writing.

For a descriptive passage to be successful, the words must convey to the reader an accurate image of what the writer actually saw. The example above does not express a clear image, so readers will either imagine something different or fail to imagine anything at all.

Now let’s look at vivid imagery as a replacement for subjective words. Consider the following alternate description:

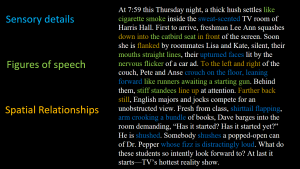

Now, compare this paragraph to the image above. Can you see how the description matches the image? Did the image in your mind at least somewhat align with the image being described? Hopefully! Here the writer used sensory details and spatial organization to convey the image observed with precision. Of course, it’s possible to overdo such efforts, but when handled well, descriptive writing becomes the unsung hero of the writer’s toolbox.

The Toolbox

- Sensory Details

- Figures of Speech

- Spatial Organization

- Specific Names

The rest of this chapter examines each of these in turn and will conclude with an exercise that lets you practice your skill.

Sensory Details

Sensory details use all five senses to show how a thing looks, sounds, smells, feels, and tastes. Watch the video below to learn more.

Figures of Speech

Figures of speech are the artistic phrases used in any way other than the literal sense. These include irony, metaphor, simile, and many more. Watch the video to see Lemony Snicket explain the difference between Literal and Figurative.

Spatial organization

Spatial organization is the use of words that indicate movement through space (up, down, left, right, etc.) which help describe a scene. Browse the Prezi presentation about organizing paragraphs (including spatial organization).

Specific Names

Let’s say your friend went for a walk and returned home to tell you about it. Which report would be more satisfying to you . . . this one?

The other day I went down a path and saw some water and some trees and some hills. There were birds in the trees.

Or this one?

On Saturday, I followed Campbell Creek Trail from Piper Street to the DeBarr overpass. North Fork Campbell Creek widens to a wetland there, with cottonwood scattered among white and black spruce. I caught glimpses of snow atop Near Point and Wolverine Peak in the Chugach front range while black-capped chickadees sang from a gnarly Birch.

The answer is obvious, of course. But these days, it’s rare to hear anyone talk that way. The second example goes further than just using sensory details and spatial organization, it names names!

Go for a walk, or a drive, or even just to the grocery store, and you’ll be surrounded by places and things that have specific names. But knowledge of those names is becoming a lost art. It takes time to build this skill, but websites like Google Maps and Wikipedia can kickstart the process. Start learning what things are called and then use those names and you’ll unlock a secret to super-powered communication!

The Toolbox in Use

- See how the Sensory Details work. Notice the sense of smell used in “sweat-scented,” visual words like “upturned faces” and “crouch on the floor,” sound words like “shirttail flapping,” “shushed,” and “fizz distractingly loud.”

- See how Figures of Speech work. Notice similes that make comparisons with the word like: “like cigarette smoke,” and “like runners awaiting a starting gun.” Notice metaphors that make comparisons directly” “catbird seat,” “mouths straight lines,” and “stiff standees.” Notice personification that treats non-human things as human: “nervous flicker.”

- See how Spatial Relationships work. These are easy. Just look for words that show an item’s position: “in front,” “flanked,” “left and right,” and “farther back.”

Now it’s your turn

Student Example

a word whose definition will vary depending on individual taste and opinion

Descriptions based on information received from your five senses.

A sensory impression transmitted from the writer to the reader.