7 Brown Bear Spins Beneath the Darkly Spinning Stars (excerpt)

Ernestine Hayes

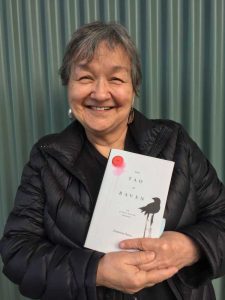

About the author

Hayes has received critical acclaim for writing that explores the complexities of Indigenous identity. She is of the Eagle moiety, a member of the Wolf House of the Kaagwaantaan clan of the Lingít (Tlingit) nation. Her art examines privilege and trauma, myth and wisdom, culture and resilience. She crisscrosses genres: creative nonfiction and poetry, fiction and children’s literature. Her piece “The Spoken Forest” was permanently installed as a Poem in Place at Totem Bight State Park in Ketchikan. Another work, “Aanka Xootzi ka Aasgutu Xootzi Shkalneegi” or “Town Bear Forest Bear,” stands out as the first children’s book published as an original story in Tlingit. As her colleague Maria Shaa Tláa Williams put it, Hayes blurs the line between poetry and prose. Two of her best-known publications are Blonde Indian: An Alaska Native Memoir, for which she received the American Book Award, and The Tao of Raven: An Alaska Native Memoir. This chapter is an excerpt from The Tao of Raven. (author bio by Don Rearden, Echoes of Alaska)

Summer days in Juneau were sweeter when I was a girl, the breezes more gentle, the sun’s rays warmer, laughter more spontaneous, the possible future imprecise but somehow bright. The distinctions that divided me from other children—wrinkled dirty clothes, absence of family at schooltime celebrations, unclean fingernails and dirty hands, no doubt a salty, unwashed smell—had eased upon my mother’s return from her long tubercular stay in the hospital, and the coming separation from my classmates that would arrive with puberty was still no more than a wistfully approaching shadow. At that in-between age, anyone I met on my summer-day wanderings might become a one-day friend. Anyone might join me for a rambling day of hiking up Mt. Roberts, wading down Gold Creek, fishing off the city dock.

So it was that morning I met two or three classmates, not quite strangers, not at all friends, white kids who lived in neighborhoods I didn’t know, who wore clothes that were purchased from places other than the mail-order catalogs my mother and I so eagerly anticipated, who attended churches where their parents—mothers and fathers praying together at elegant polished pews, walking hand in arm from dusted doorstep to reserved parking place, living together in veiled discontent and virtuous disapproval—or was that simply what I’d already learned to tell myself in order to construct solace in an unconsoling world—gave thanks to a just god that had arranged their success and guaranteed their continued rewards and those of their blessed children, in whom they were all so well pleased. After some hellos, we decided to walk over to the docks to try out the new fishing pole one of them had just been given by his father. I promised to take a picture with my mother’s Kodak she had lovingly consigned to me for the summer.

The experience of fishing off the docks was always marred for me by the sight of the struggling gasping creature, eyes bugged, delirious, terrified, bloody hook pulling at its thin lip, fighting with all the might of its soon-to-be succulent flesh for the freedom of the green water lapping the slimy barnacle-covered pilings beneath our feet. My own escapades at fishing had mainly been limited to hunting for already-severed halibut heads outside the loud wide doors of the cold storage which in a year or two would burst into a fire so large it woke the whole town, including my mother, who would walk me by the hand to witness the extraordinary sight of high flames lighting the unstarred darkness.

Our chatter was that of children, the excitement of a nibble now and then neither fulfilled nor defeated by success or by failure. It was enough to be alive. I sensed the possibilities contained in friendship with these extraordinary children, the promise of entry, a relief from freedom, the security of belonging. Along with their friendship might come comfort, might come knowledge, might come understanding. Along with their friendship might come acceptance. I might be included. I might belong.

The blond-haired boy began to snicker. “Look at that drunk Indian carrying that fish. Let’s get out of here.” He pointed southward down the dock and began to wind in his line. I followed his eyes in the direction of his pointing finger to see an old man in a greasy wool jacket, dark fisherman’s knit cap covering his head, a fresh halibut glistening from a length of twine wrapped around his fist.

I squinted. “That’s my grandfather,” I announced to the boy and his fidgety, giggling companions.

Everyone tried to be quiet as my grandfather walked toward us. The other children, their derision ill-concealed by poor attempts to cover their snorts of laughter, took hesitant steps backward as my grandfather neared. Finally we all stood too close to one another, within the distance of a man’s height, his reach, his life, the white children I’d dared to imagine as my friends staging their retreat behind me, ready to dash for the safety of another world, my grandfather in front of me, offering a whiskered smile, saluting me with the heavy flatfish he proudly held up for my regard and admiration, I at the torn seam of two worlds, dreams faded like dappling sunlight, the only choice no choice at all, to embrace the life that had been designed for me no less than the lives that had been designed by these children’s parents for us all, to give back the proud smile my grandfather offered, to know that despite the fish slime, despite the days-old whiskers, despite the headache and lost fingers and sharp grief, here was a man who understood what it meant to be proud.

I took his picture and gave him a hug. I admired the salt-fresh fish. We both knew he would sell it to some lucky cook and would use the money to buy more wine. We both knew it would take far more than a sunny afternoon for me to make friends of those softened, pink children. We both knew that those children’s fathers, though they ran the town and ran the schools and ran the courts and ran our lives, would never possess the courage that my grandfather showed every day by simply waking up and going on. We both knew that even though halibut cheeks were my mother’s favorite summer meal and even though there was no chance that we might fry one up tonight, my grandfather loved me as much as any grandfather had ever loved his wild unreliable unpredictable grandchild.

The next time I saw those children, as we passed each other in the halls of the school designed to exalt them, we didn’t speak.

Having symptoms of the disease tuberculosis, which affects the lungs and makes breathing difficult.