15 About the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act

ANCSA Regional Association (ARA)

Aside from statehood itself, no other single piece of legislation has had a greater effect on the lives of Alaskans than the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA). Just drive around Anchorage for the evidence: see the shiny office buildings of corporations with names like NANA, CIRI, Bearing Strait, Bristol Bay, and more. Those are the corporations created by ANCSA. The village network of rural Alaska was also shaped by this law, as were the way oil is extracted and sold and the money distributed. It’s a big deal. But I find that actual residents, even those of Native heritage, often know little or nothing of this influential law. It’s time to change that. Read on for an excellent overview of ANCSA written by staff at ANCSA Regional Association (ARA), the body that oversees and helps connect the 12 regional organizations with each other.

Introduction

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 (ANCSA) was a new approach by Congress to federal Indian policy. ANCSA extinguished aboriginal land title in Alaska. It divided the state into twelve distinct regions and mandated the creation of twelve private, for-profit Alaska Native regional corporations and over 200 private, for-profit Alaska Native village corporations. ANCSA also mandated that both regional and village corporations be owned by enrolled Alaska Native shareholders. Unlike in the lower-48 states where the reservation system was the norm, ANCSA departed significantly–its foundation was in Alaska Native corporate ownership.

Through ANCSA, the federal government transferred 44 million acres–land to be held in corporate ownership by Alaska Native shareholders–to Alaska Native regional and village corporations. The federal government also compensated the newly formed Alaska Native corporations a total of $962.5 million for land lost in the settlement agreement.

ANCSA had expansive effects, reaching far beyond Alaska Native people. The passage of ANCSA allowed for federal lease sales to move forward across Alaska, with proceeds going to the federal government. Oil and gas exploration on the North Slope of Alaska and the construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System created thousands of jobs and pumped revenues into the state coffers eventually leading to the creation of the Alaska Permanent Fund. Since the passage of ANCSA, various industries have been strengthened in Alaska, creating jobs in both the private and public sectors. By creating Alaska Native-owned, for-profit corporations, ANCSA also brought additional economic diversity to the state that has benefited, either directly or indirectly, all Alaskans.

To understand ANCSA, it is important to understand the history of aboriginal land claims in Alaska. More than 100 years prior to the enactment of ANCSA, Alaska was purchased from Russia. From the time of purchase until the passage of ANCSA, aboriginal land claims were not definitively addressed by the federal government.

Timeline of Significant Events: How ANCSA Came To Be

Below is a timeline that outlines how failure by Congress to address aboriginal land claims in decades worth of legislation led to the eventual passage of ANCSA in 1971. Federal legislation from the Treaty of Cession to the Statehood Act did not explicitly address aboriginal land claims, leaving it to finally be dealt with by Congress 104 years after Alaska was purchased from Russia.

1867: The Treaty of Cession The United States purchases Alaska from Russia

In 1867, the Treaty of Cession was signed. The treaty outlined the terms for the sale of Alaska from Russia to the United States. The United States paid $7.2 million for Alaska.

The Alaska Native peoples who had inhabited Alaska for thousands of years disagreed with Russia right to sell their land. The Russian claim to aboriginal lands of Alaska was under the Laws of Discovery, which state the two conditions aboriginal people can lose their land: 1) through a just war, or 2) by giving up specific land in a treaty. Neither of these conditions applied to the Alaska Native people, which left land claims unresolved when the purchase took place.

1884: The First Organic Act for Alaska becomes a civil and judicial district of the United States

When the Organic Act of 1884 was passed by Congress, it established the civil and judicial district of Alaska. Status as a civil and judicial district allowed the non-indigenous residents of Alaska to stand up a civil government, which included a district governor, a district court with a judge and court clerk, four commissioners, and a United States marshal.

The Organic Act of 1884 marginally addressed land issues relating to mines and mineral privileges. The act also specifically mentioned Alaska indigenous peoples (calling them Indians) and their occupation of the land, but did not resolve their land claims. The act states:

The Indians or other persons in said district shall not be disturbed in the possession of any lands actually in their use or occupation or now claimed by them but the terms under which such persons may acquire title to such lands is reserved for future legislation by Congress.

1912: The Second Organic Act for Alaska becomes a territory of the United States

The Second Organic Act established Alaska as an incorporated United States territory, which allowed Alaska to elect a territorial delegate to Congress, elect legislators to a territorial legislature, and elect a territorial governor. The Second Organic Act outlined the laws for territorial elections and the purview of elected officials.

The Second Organic Act included no specific language addressing aboriginal land claims, leaving them to be dealt with by Congress in the future.

1959: The Alaska Statehood Act of 1958 Alaska becomes the 49th state of the United States

In 1958, Congress passed the Statehood Act, which made Alaska the 49th state of United States, effective on January 3, 1959. The Statehood Act established a state government, defined elected representation for the state in Washington, D.C., and outlined the types of public lands that the state could select.

Again, the Statehood Act did not specifically address comprehensive land claims by Alaska indigenous peoples. The Statehood Act did, however, declare that the

State must disclaim all right and title to lands and other property not granted or confirmed to the State including right or title which may be held by any Indians, Eskimos or Aleuts (natives) or is held by the United States in trust for said natives.

The act went on to state that any land that may belong to natives shall be under the jurisdiction and control of the United States.

Because Congress did not resolve the issue of aboriginal land claims outright, it was around this time that Alaska Native leaders began to organize into groups to represent their respective regions as they sought resolution to their land claims.

1966: The Alaska Federation of Natives is formed to advocate for a land claims settlement

The Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN) formed in 1966 in response to the land claims issues that were being brought forth by various organized Alaska Native groups. AFN consolidated the various Alaska Native groups efforts and became the statewide organization to advocate for aboriginal land claims.

AFN earned an early victory in 1966 when then-Secretary of Interior Stuart Udall imposed a land freeze. AFN delegates pressed for the land freeze to stop land selections and conveyances across the state, which were viewed by Alaska Native people as encroachment on their lands. By freezing all land conveyances within Alaska, Secretary Udall forced the State of Alaska, the federal government, and the Alaska Native people to resolve aboriginal land claims before any further land selections could take place.

The late 1960s: Commercial quantities of oil are discovered on the North Slope of Alaska

In the late 1960s, commercial quantities of oil were discovered on the North Slope of Alaska. To get the oil to market via the Gulf of Alaska, it first needed to traverse the state from the North Slope all the way down to Valdez. The proposed Trans-Alaska Pipeline system (TAPS) would need to cross over land that various Alaska Native groups claimed. With Alaska Native land claims still unsettled and the land freeze in place, the proposed construction of TAPS was put on hold. Further oil exploration and development also stalled.

These circumstances put Secretary Udall land freeze in the spotlight in both Washington, D.C. and in Alaska. The oil and gas industry and early environmentalist organizations entered the land claims debate, adding more voices and complexity.

1971: The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 Federal government explicitly addresses aboriginal land claims in Alaska

After intense internal negotiations among the various Alaska Native groups and between Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN) delegates and representatives of state and federal government, Congress finally passed Alaska Native land claims legislation in 1971. On December 18, 1971, President Richard Nixon addressed the delegates of AFN by phone and informed them that he had just signed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act into law.

At the time of its passage, ANCSA was entirely different than any previous federal Indian policy. ANCSA extinguished aboriginal land claims in Alaska and mandated a for-profit model with land title under corporate ownership. Upon the passage of ANCSA, a new era began for Alaska Native people. Many of the early leaders of the Alaska Native regional corporations had never worked in a corporate business and few had college degrees, let alone advanced degrees in business or law. Despite the humble beginnings, Alaska Native regional corporations have become an integral part of the Alaska economy.

The Mandates of ANCSA

December 18, 1971 marked a new era for federal Indian policy. It was also a significant day for Alaska Native peoples on an individual level. Several provisions of ANCSA affected individuals in ways that neither they nor the federal government really understood at the time.

ANCSA original language addressed the specific congressional mandates of Alaska Native corporations: government oversight of the corporations, eligibility requirements to enroll shareholders, the land selection process, redistribution of monetized natural resource wealth among regional and village corporations, and more. There have also been significant amendments to ANCSA since its passage, most notably the 1991 amendments.

The Twelve Regions, a Federal Indian Reservation, and a Thirteenth Regional Corporation

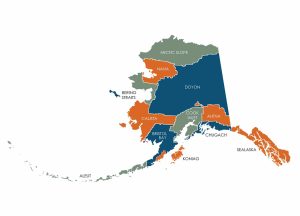

ANCSA divided Alaska into twelve regions defined by the common heritage and shared interests of the indigenous peoples within each geographic area. The regional boundaries established which people, villages, and communities that each Alaska Native regional corporation would serve. The boundaries do not directly represent land ownership; they did, however, define the areas in which each regional corporation could select lands to be conveyed under the provisions ANCSA. Today, within each region there is a complex landscape of governance, land ownership, roles, and relationships.

At the time Congress passed ANCSA, the Metlakatla Indian Community opted out of the settlement agreement. The community instead chose to be designated as a federal Indian reservation. The Annette Island reserve is the only federal Indian reservation in the state of Alaska.

In 1975, ANCSA was amended to create a thirteenth Alaska Native regional corporation, known as the 13th Regional Corporation. The 13th Regional Corporation was established to ensure that Alaska Native people who were not permanent residents of Alaska but who were otherwise eligible to enroll in an Alaska Native regional corporation were included in the land claims settlement. Unlike the original Alaska Native regional corporations, the 13th Regional Corporation did not receive any land conveyances under ANCSA; therefore, it cannot contribute any 7(i) funds; it is, however, eligible to receive 7(i) funds from the other Alaska Native Regional corporations. In 2013, the 13th Regional Corporation was involuntarily dissolved by the State of Alaska when their registered agent resigned.

Original Shareholder Enrollment (1971-1991)

Each Alaska Native regional and village corporation had to enroll shareholders within two years from the date that ANCSA was signed into law. This was no small task; Alaska Native people were spread across vast distances in every region, often with no roads connecting homes and communities. When the two-year deadline arrived, the twelve Alaska Native regional corporations had enrolled just over 64,000 original shareholders, each of whom received 100 shares.

The original language in ANCSA defined the eligibility requirements for enrollment in an Alaska Native corporation. It was not until the 1991 amendments to ANCSA were passed that individual Alaska Native corporations, through a vote of their shareholders, could amend their articles of incorporation to expand shareholder enrollment eligibility.

In particular, two requirements of original shareholder eligibility are noteworthy: blood quantum and date of birth.

ANCSA defined native as: a citizen of the United States who is a person of one-fourth degree or more Alaska Indian (including Tsimshian Indians not enrolled in the Metlakatla Indian Community) Eskimo, or Aleut blood, or combination thereof. Meaning only Alaska Native people of blood quantum were eligible to be enrolled in an Alaska Native corporation (regional or village). ANCSA did define other ways around this.

Only those Alaska Native people of one-fourth blood quantum who were born on or before 11:59 p.m. on December 18, 1971 were eligible to enroll in Alaska Native regional and village corporations. Those born on December 19, 1971 or after were not eligible.

Land Selection Process

ANCSA language stated that Alaska Native regional and village corporations would be conveyed a total of nearly 44 million acres of land in Alaska, about ten percent of the state. However, there were large tracts of land across all twelve regions that the federal government had already claimed for strategic purposes or conveyed to other entities. Because those lands were not eligible for selection by Alaska Native corporations, the corporations were compensated $962.5 million for lost lands.

The land selection process defined in ANCSA was different for Alaska Native village corporations and Alaska Native regional corporations. Alaska Native village corporations were to select lands on which any part of the village was located. For the most part, Alaska Native village corporations received title to the surface rights of those lands. In contrast, Alaska Native regional corporations were to select any lands from within the larger regional boundaries defined in ANCSA. Alaska Native regional corporations received title to the subsurface estate of much of the land they selected. Consequently, most of the Alaska Native regional corporations balanced their land selections between areas that had significant cultural or subsistence value and areas that had potential economic value for natural resource development.

Since the passage of ANCSA, some Alaska Native corporations still have not received their full conveyance of land. In addition, a number of Alaska Native corporations have engaged in land transfers with state and federal agencies and with other Alaska Native corporations, resulting in a mix of surface and subsurface rights owned by regional and village corporations.

The Revenue Sharing Provisions of ANCSA: Sections 7(i) and 7(j)

From the beginning of the land claims debate there was recognition that some regions were richer in natural resources and therefore had more potential for economic development. Congress and various Alaska Native groups felt a mechanism was needed to address the issue of regional natural resource haves and have nots. In the years leading up to the passage of ANCSA, several iterations of the land claims bill introduced in Congress attempted to address the disparity in natural resource wealth between the regions when calculating land conveyances and compensation for land lost.

The revenue sharing provisions that ultimately passed as a part of ANCSA were contained in sections 7(i) and 7(j). The goal of the sections is to ensure that all Alaska Native corporations, and accordingly their shareholders, benefit from revenues derived from natural resources developed on ANCSA lands. While typical for-profit corporations would balk at these provisions, many people believe that without sections 7(i) and 7(j), ANCSA would not have passed.

The original language of Section 7(i) states:

Seventy per centum of all revenues received by each Regional Corporation from the timber resources and subsurface estate patented to it pursuant to this Act shall be divided annually by the Regional Corporation among all twelve Regional Corporations organized pursuant to this section according to the number of Natives enrolled in each region pursuant to Section 5.

Section 7(i) requires that any annual revenues that an Alaska Native regional corporation receives from ANCSA lands (e.g., from timber resources or natural resources in subsurface estate) must be shared in a 70/30 split. The allocation means that 70 percent of the revenue is dispersed to the other Alaska Native regional corporations and the remaining 30 percent of the revenue is kept by the Alaska Native regional corporation that developed the natural resource.

Section 7(j) ensures revenues from natural resource wealth are also shared with Alaska Native village corporations. Section 7(j) directs Alaska Native regional corporations to disperse 50 percent of the Section 7(i) revenues they receive to Alaska Native village corporations within the region. Unlike Section 7(i), Section 7(j) does not require any revenue sharing distribution from Alaska Native village corporations to other village corporations or to regional corporations.

The original language of Section 7(j) states, in part:

Not less than 45% of funds from such sources during the first five-year period, and 50% thereafter, shall be distributed among the Village Corporations in the region and the class of stockholders who are not residents of those Villages, as provided in subsection to it.

To address issues that were not foreseen at the time ANCSA was passed, Section 7(i) has been amended a few times to address issues that have arisen since 1971.

Despite the ongoing debate about specifics of the revenue sharing provisions, the redistribution of natural resource wealth has generally had positive effects on all regions. In 2018, the ANCSA Regional Association commissioned a report by the McDowell Group on the economic impacts of sections 7(i) and 7(j) of ANCSA. Some key findings of that report are:

- Every Alaska Native regional corporation has had periods when it received more 7(i) payments than it paid out so each of the twelve Alaska Native regional corporations (and therefore the shareholders of each corporation) has been a Section 7(i) beneficiary

- The redistribution of wealth among the regions that receive 7(i) revenues creates a leveling effect in economic activity that otherwise would not occur

*McDowell Group A summary of the economic benefits of ANCSA section7(i) and 7(j)

The 1991 Amendments

Several original provisions of ANCSA that dealt with stocks and shareholder eligibility were set to expire in 1991, twenty years after passage of the bill. Expiration of the provisions presupposed that between 1971 and 1991, Alaska Native shareholders would gain a strong grasp of corporate ownership and activities and be ready to make significant decisions that would potentially impact Alaska Native ownership of the government-created corporations.

However, as the conclusion of the twenty years neared, the overall profitability and success of Alaska Native corporations was not where Congress had anticipated it to be. Therefore, in 1988, Congress passed amendments to ANCSA addressing provisions relating to the sale of stock, exemption from federal securities laws, and the expansion of eligibility of shareholders.

The series of amendments was passed in 1988 but because all amendments addressed changes to ANCSA that were to occur in 1991, they are often referred to as the 1991 amendments. While ANCSA has been amended numerous times since its passage, the 1991 amendments have been the most significant to Alaska Native corporations and their shareholders.

Prohibition of the Sale of Stock

As originally written in 1971, ANCSA had a twenty-year prohibition on the sale of Alaska Native corporation stock. In other words, stock in Alaska Native corporations could not be sold until 1991. In 1988, ANCSA was amended to prohibit the sale of stock in perpetuity, unless the shareholders of an Alaska Native corporation voted to amend the articles of incorporation of their corporation to remove restrictions on stock sales. To date, no Alaska Native corporation has amended their articles of incorporation to allow for the sale of stock.

While stock cannot be sold or traded, original stock (i.e., stock issued to those born on or before December 18, 1971) can be gifted, willed, or bequeathed.

The Exemption from Some Federal Securities Laws

Originally, ANCSA exempted Alaska Native corporations from some federal securities laws for twenty years. Because Alaska Native corporation stocks were not eligible to be sold or disposed of during the twenty-year period after the passage of ANCSA, many federal securities laws did not apply.

Because the 1991 amendments extended the prohibition of the sale of stock into perpetuity, accordingly the exemption of Alaska Native corporations from certain federal securities laws was also extended.

Expansion of Shareholder Eligibility

To individual Alaska Native people, one of the most significant of the 1991 amendments (and a subsequent amendment in 1992) was the expansion of shareholder eligibility. The amendments addressed the eligibility of Alaska Native people who missed the original enrollment deadline and the date-of-birth cutoff of December 18, 1971.

The initial amendment allowed a corporation’s shareholders to vote to amend its articles of incorporation to add new shareholders. In 1992, an amendment clarified and expanded how shareholders of an Alaska Native corporation could allow for additional shares to be issued to descendants of Alaska Native shareholders. The 1992 amendment also removed the blood quantum requirement originally set by ANCSA.

For an Alaska Native corporation to expand shareholder eligibility and allow for additional shares to be issued, the shareholders of that specific Alaska Native corporation must vote to amend their articles of incorporation. To date, six of the twelve Alaska Native regional corporations’ original shareholders have voted to open their rolls to those born after December 18, 1971, resulting in a larger shareholder base.

Source:

ANSCA Regional Association, “About the Alaska Claims Native Settlement Act,” ARA, 2021.

native