11. Basic Design and Readability in Publications

The way a text looks matters to a reader, so it should matter to a writer. Letters, reports, and blogs are more than just words on a page or a screen. How ideas are arranged and delivered in physical form, whether electronically or on paper, can make reading seem intimidating, confusing, or downright unfriendly, even if the content itself is perfect. Your text is like a room for your ideas. Sometimes you want readers to get in and get out quickly, but often, you want them to sit down and make themselves comfortable, to put their feet up and stay awhile. Whatever the case, you should be in control of the reader’s experience.

And most readers are a lot like TV viewers with remote controls. In a moment, their attention is diverted to another channel if something about your content puts them off. It’s important to get their attention and hold it. Good content is a key part of this, of course, but the visual presentation of your content matters too. Reading is a difficult, cognitively demanding task, so if your design helps make your readers’ journey through the text easier, you will hold their attention longer. Give readers reasons to linger, and they will.

|

|

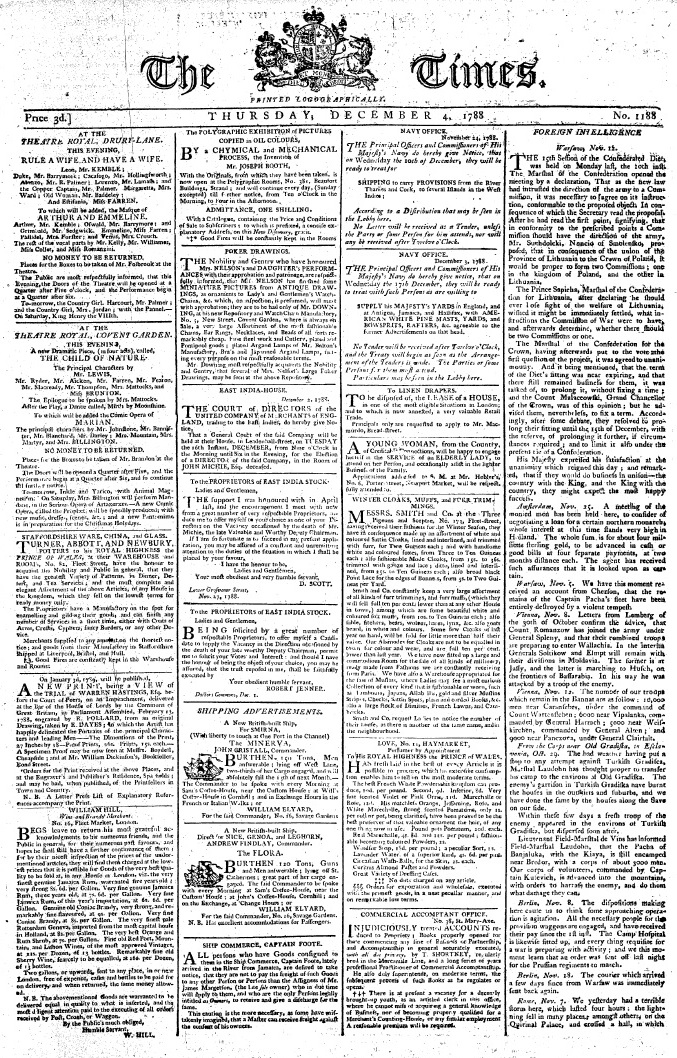

Figure 1: Where do you want to spend the next two hours? Image Credit: “World’s Messiest Office Cubicle Discovered in Colorado” by Jeffrey Beall is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0; “laptop iphone” is in the Public Domain, CC0.

Good document design is both science and art. The particular design of a document—what it contains, what color scheme it follows, what alignment strategy it reflects, and so on—is the result of a series of choices made by the designer. It takes a long time to master the finer points of design, and this chapter won’t turn you into a designer, but it will offer some simple ways of thinking that will help you strategize about how to make your document intuitive and reader friendly—easy to scan, search, and read.

This is not a chapter on design per se; rather, it will familiarize you with a few basic truths and a way of thinking that all designers know well. Whether you’re typing up a memo on new safety policies at work, producing a newsletter for your community group, or putting together a booklet describing the new app you just finished and wish to market, you need to think about a few basic elements of document design.

ACTIVITY: Discuss texts that you have found intimidating or hard to read because of their layout or appearance. What exactly made the text difficult to read?

You already engage in some basic document design practices. For instance, when you format an academic essay, you center your title and regularly break to a new paragraph, which signals to the reader that it’s time for a breather, the content is shifting slightly, or you are moving on to a completely new topic. You illustrate blogs, Web pages, and PowerPoint slides with photos and graphics, animations, or videos. Even small elements of your writing help guide readers: indentation, changes in type style (bold, italics, underline), or the punctuation at the end of a sentence.

Professional writers, especially those who work for well-funded web sites and mass-market print publications (like newspapers and magazines) are lucky enough to have the services of artists, graphic designers, skilled photographers, and layout experts. But most of us just want to have a cooler-looking blog, a more professional-looking report, or an eBay listing that doesn’t make buyers suspect our credibility.

This chapter briefly summarizes some fundamental concepts that you should consider as you revise and shape your text, whether it is in print or electronic form. Then, you will read about and see examples of some basic principles of document design that allow writers to combine graphic elements and text to convey a message to an audience.

CHAPTER ATTRIBUTION INFORMATION

This chapter was written by Jodi Naas, Portland Community College, and is licensed CC-BY 4.0.