14 Appendix F: Punctuation Matters

“Punctuation marks are the road signs placed along the highway of our communication, to control speeds, provide directions and prevent head-on collisions.”

Pico Iyer, “In praise of the humble comma”[1]

Punctuation Really Matters!

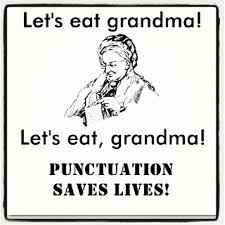

Consider how punctuation can change the meaning of the following run-on sentence:

I have two hours to kill someone come see me.

The main function of punctuation is to separate phrases and clauses into meaningful units of information. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the basic structure of sentences—phrases and clauses—to understand the proper uses of punctuation. When punctuation is missing or incorrectly used, the reader may get a completely different message than the one intended. This can not only confuse readers and waste time, but can have disastrous results in cases where the writing has legal, economic, or safety implications.

An example of how a punctuation error can have real world costs and consequences is reported in “Comma Quirk Irks Rogers”: one comma error in a 10-page contract cost Rogers $2 million.[3] If you need further evidence, read about the case of the trucker’s comma that went all the way to the supreme court, resulting in a $10 million dollar payout![4]

There are several helpful rules that will help you determine where and how to use punctuation, but first, it might be helpful to understand the origins. Punctuation was initially developed to help people who were giving speeches or reading aloud. Various kinds of punctuation indicated when and for how long the reader should pause between phrases, clauses, and sentences:

Comma = 1 second pause

Semicolon = 2 second pause

Colon = 3 second pause

Period = 4 second pause

These “pause rules” can still offer some guidance, but they are not foolproof, as there are many reasons that someone might pause while speaking, including that they simply ran out of breath, got distracted, or need time to think of a word. Below are some more consistent rules that you should follow to properly punctuate your sentences. These are presented in a numerical order to help you remember the rules more easily.

As we have discussed before, sentences are most often strongest when the subject is the first element of the sentence: S → V → O

Occasionally, however, we might want to place a word or phrase before the subject. In cases where you want to do this, it can be helpful, and often necessary, to place a comma after that word or phrase to clearly indicate the subject of the sentence. In the following sentence, see if you can determine what the subject is without a comma to help you:

Based on that initial design concepts will be generated.

The subject—and therefore the meaning of the sentence—depends on where you place the comma. If the initial phrase is “Based on that,” and “that” refers to some previously stated idea, then the sentence indicates that the subject is “initial design concepts,” and the verb is “will be generated.” However, if the initial phrase is “Based on that initial design,” then we already have an initial design to work from and do not have to generate one. We are now focusing on creating more advanced “concepts,” that will be “based on that initial design.”

So if the subject is not the #1 word in your sentence, place a comma before it to clearly show what the subject is (hence “comma rule #1”). In each of the following examples, the subject of the main clause is bolded.

| After an introductory word | Finally, the design must consider all constraints. |

| After an introductory phrase | In the initial phase, the design must meet early objectives.

Meeting all the client’s needs, this design has the potential to be very successful. Unlike Emma, Karla loves mechatronics. |

| After a subordinate clause | If the design meets all the objectives, we will get a get a raise.

Although we are slightly over budget, the design will be cost effective overall. While he interviews the client, she will do a site survey. |

When you place an interrupting word, phrase, or clause between the subject and verb, if that phrase is a non-essential element, you must enclose that phrase in commas (use the “bracket test”: if you could enclose it in brackets, then you can use commas). If the phrase is essential to the meaning, omit the commas. The words interrupting the subject and verb are bolded in the examples below.

| Interrupting word | Communication errors, unfortunately, can lead to disastrous design flaws.

The rules, however, are quite easy to learn. |

| Interrupting Non-Essential Phrase or Relative Clause

(these could be bracketed, and even omitted, without changing the meaning of the sentence) |

The Johnson street bridge, commonly known as the “Blue Bridge,” had to be replaced.

The new bridge, completed last year, is a rolling bascule design. The new bridge, which is a rolling bascule design, was completed last year. |

| Interrupting Essential phrases or clauses

do not use commas; these are essential to the meaning of the sentence |

The objective that is most critical to our success is the first one.

That bridge that needed replacing was the Blue Bridge. The man with the yellow hat belongs to Curious George. The student who has the best design will get an innovator’s award. |

If you would like more information on Essential vs Non-Essential elements, and when to use “that” vs “which,” check out this Grammar Girl link: Which versus That

Beware the “Pause Rule”—many comma rule 2 errors occur when a sentence has a long subject phrase followed by the verb “is.” People have the tendency to want to place a comma here, even though it is incorrect, simply because they would normally pause here when speaking:

The main thing that you must be sure to remember about the magnificent Chinese pandas of the southwest, x is that they can be dangerous.

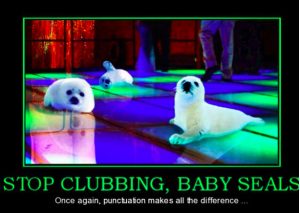

Whether you are listing 3 or more nouns, verb, adjectives, phrases, or even clauses, use commas to separate them. In general, do not place a comma before the first item or after the last item. If you are only listing two items, do not separate them with commas. Note what happens when you forget to put commas in the following sentence:

“I love cooking my family and my pets.”

The author may have intended to list three things that she loves, but without punctuation, she ends up listing two things she loves to cook.

Only use the commas if there are three or more elements being listed. Make sure to list the elements in a consistent grammatical form (all nouns, or all verbs, or all using parallel phrasing).

| 2 listed elements

(no commas needed) |

All initial designs must incorporate mechanical structures and electrical systems. (2 nouns)

Squirrels eat acorns and sleep in trees. (1 subject + compound verb (2 verbs) |

| 3 listed elements | The final design must incorporate mechanical, electrical, and software subsystems. (3 adjectives describing different subsystems)

Squirrels eat acorns, sleep in trees, and dig holes in the garden. (3 verbs) The proposed designs must not go over budget, use more than the allotted equipment, or take longer than 1 week to construct. (3 verbs: go, use, and take) |

| faulty parallel phrasing

(one of these things is not like the others…) |

Proposed design concepts must adhere to all constraints, meet all objectives, and the components x must be on the approved list. (2 verbs and a 1 noun)

The new bridge is aesthetically pleasing, structurally sound, and has x a pedestrian walkway. (2 adjectives and 1 verb) |

There is some debate about whether to place a comma before the “and” used before the final listed item. This comma, referred to as the Oxford Comma as it is required by Oxford University Press, is optional in many situations. For an optional piece of punctuation, has stirred up a surprising amount of controversy! As with most grammatical rules, they can be broken when it is prudent and effective to do so; use your judgment, and choose the option that achieves the most clarity for your reader.

While you might occasionally omit commas if the two clauses you want to join are very short (“She drove and he navigated.”), it is a good habit to separate them with a comma for the sake of clarity. The mnemonic device for remembering the coordinating conjunctions that can link two independent clauses together is FANBOYS (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so). When you have two complete sentences, but you want to join them together to make one larger idea, use a comma before the coordinating conjunction.

| FANBOYS | Two clauses joined by a comma and coordinating conjunction |

| , for | Thanks goodness next week is reading break, for we all need rest. |

| , and | Vampires drink blood, and zombies eat brains. |

| , nor | You should not play with vampires, nor should you hang around with zombies. |

| , but | The undead are not acceptable playmates, but werewolves are ok. |

| , or | You can simply avoid werewolves during the full moon, or you can lock them in the basement. |

| , yet | Some rules of etiquette suggest it is rude to lock someone in the basement, yet safety is of paramount concern. |

| , so | I think you understand my concerns, so I will leave it at that. |

Learning comma rules takes practice, of course.

Practice makes perfect, in the long run.

Vampires make everyone nervous, even the bravest slayers.

I told you I need it by Wednesday, not Thursday.

Consider the difference between “It’s raining cats and dogs” and “It’s raining, cats and dogs.”

A semicolon has three main functions:

1. Join closely related independent sentences into one sentence:

Scott was impatient to get married; Sharon wanted to wait until they were financially secure.

(Subject are strongly related — indeed, in this case, they are engaged!)

2. Link two sentences joined by a transitional phrase/conjunctive adverb (however, therefore, finally, moreover, etc.):

Canadian History is a rather dull class; however, it is a requirement for the elementary education program.

3. Separate items in a complex list where one or more of the items have internal punctuation:

The role of the vice-president will be to enhance the university’s external relations; strengthen its relationship with alumni, donors, and community leaders; and implement fundraising programs.

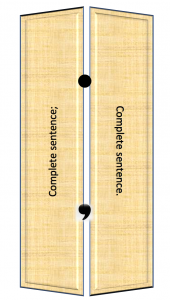

In the first two cases, a semicolon works the same way a period does; if you could put a period there, then you can put a semicolon there. The semicolon simply connects the ideas more closely as part of one key idea, and makes the pause between them a little shorter.

The main rule you must remember is that if you use a semicolon in this way, the clauses on either side of the semicolon must be complete sentences. You cannot use a semicolon to introduce a phrase or fragment.

Complete sentence; complete sentence.

Think of the semicolon as working like a hinge in a bi-fold door; it joins two complete door panels that each have their own frame together as one.

Also remember that you cannot simply use a comma instead of a semicolon to link the two clauses; that would result in a comma splice error.

The 3rd case–using semicolons to separate long, complex list items that contain commas within them–can result in complicated sentences that are difficult to read. You might consider using a bullet list instead of an in-sentence list in these cases.

How would you punctuate the following to clearly show how many courses Makiko is taking?

Makiko is taking Classics, a course on the drama of Sophocles, Seneca, Euripides, Fine Arts, a course on Impressionism, Expressionism, Modernism, Literature, a course on Satire, Pastiche, Burlesque, and Science, a new course for Arts students.

- Many companies make sugar-free soft drinks that are flavored by synthetic chemicals the drinks usually contain only one or two calories per serving.

- The crab grass was flourishing but the rest of the lawn unfortunately was dying.

- The hill was covered with wildflowers it was a beautiful sight.

- The artist preferred to paint in oils he did not like watercolors.

- The house was clean the table set and the porch light on everything was ready for the guests’ arrival.

- The computer could perform millions of operations in a split second however it could not think spontaneously.

- The snowstorm dumped twelve inches of snow on the interstate subsequently the state police closed the road.

- We invited a number of senior managers including Ann Kung senior vice-president Lionel Tiger director of information technology and Marty Sells manager of marketing.

Keep in mind that when correctly used, colons are only placed where the sentence could come to a complete stop (i.e: you could put a period there instead).

| Amplification | The hurricane lashed the coastal community: within two hours, every tree on the waterfront had been blown down. |

| Example | The tour guide quoted Gerald Durrell’s opinion of pandas: “They are vile beasts who eat far too many leaves.” |

| List | Today we examined two geographical areas: the Nile and the Amazon. |

Remember that when introducing a list, example, or quotation with a colon, whatever comes before the colon should be a complete sentence. You should not write something like this:

Today we examined: x

Three important objectives we must consider are: x

If these cannot end in a period, they should not end in a colon. Whatever comes after the colon can be a fragment or list; it does not have to be a complete sentence.

- Download the attached Punctuation Exercise (.docx) document and compete the exercises with a classmate.

- Choose a paragraph from the Pico Iyer’s Time Magazine article, “In praise of the humble comma,” and examine how he has used punctuation to demonstrate his point in that paragraph. In particular, note how he not only explains the importance of punctuation, but also shows its use in action.

- P. Iyer, "In praise of the humble comma," Time, 24 June, 2001 [Online]. Available: http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,149453,00.html ↵

- [Grandma image]. [Online]. Available: https://91rules.wordpress.com/2011/10/14/who-knew-commas-could-be-so-important/. CC-BY 2.0. ↵

- G. Robertson, "Comma quirk irks Rogers," The Globe and Mail, Aug. 6, 2006 [Online]. Available: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/comma-quirk-irks-rogers/article1101686/ ↵

- M. Norris, " A few words about that ten-million-dollar serial comma," The New Yorker, March 17, 2017 [Online]. Available: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/a-few-words-about-that-ten-million-dollar-serial-comma ↵

- [Baby seals image]. [Online]. Available: https://www.flickr.com/photos/venditti_min_min-venditti/30088824650. CC-BY 2.0. ↵