23 Writing for Community Change

Elisa Stone

As a college student, it’s easy to get hung up on the consumer aspects of your education: having to pay tuition and fees, paying obscene amounts for textbooks you may not end up using again, balancing work and studies, and avoiding being a starving student. You may even have a family to take care of, whether it’s fur kids or human kids or loved ones, on top of getting yourself an education. No one could argue that it takes an act of courage and dedication on your part to do what you’re doing right now.

Once you jump through all the hoops, finish all your classes, and proudly display your degree, you’ll go on to your next degree or delve into your career, which will present a new set of obligations and challenges. Either way, life tends to be busy and stay busy.

Still, college is about more than an education, more than just taking class after class, semester after semester, to get to where you want to go. College was designed to teach us to be whatever it is we want to be when we grow up (assuming we do grow up at some point), but it is also intended for a larger purpose: to make us good citizens. We live in a country where we elect our leaders and make choices about many aspects of our lives; we are allowed to voice our opinions, requests, and even demands to our elected officials. With this privilege comes an obligation, and that obligation is to be contributing members of society who work toward the greater good of all.

Why should you care? Well, maybe you don’t care, right at this moment, since we already covered how busy you are and how stressed you must be and how little sleep you are probably getting. Still, research shows that what makes people truly happy tends to involve working toward a cause outside of their own immediate needs and wants: in other words, service to others actually improves your own well-being.

What does this mean in a college setting? Ernest Boyer, President of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and former U.S. Commissioner of Education, reminds us that “the academy must become a more vigorous partner in the search for answers to our most pressing social, civic, economic, and moral problems, and must reaffirm its historic commitment to what I call the scholarship of engagement.” He says that colleges and universities must be staging grounds for action if we are to provide in-depth learning for students and meaningful opportunities for improving the world around us.

What does this have to do with writing? Or you? Our College has a history of combining service and learning in ways that allow students to gain hands-on experience, write for audiences outside of their classrooms, and change the way they see their role in the communities around them. Service-learning is an opportunity not to be missed! Many of your professors will support the idea that you can use college writing assignments to create texts that will help communities change for the better.

Let’s take an example. Technical Writing is one of the core composition classes students can take as an alternative to English 2010. One semester, SLCC’s Thayne Center for Service & Learning was approached by a local family called the Ahuna family. They had created a performance group to travel to various community events and share their family’s traditional Hawaiian songs and dances with others, and at the same time honor and preserve their cultural heritage. “Ohana” is a Hawaiian word for “family,” and so they called themselves “Ahuna Ohana,” for the Ahuna family. They needed help with publicity. They wanted a logo, a website, and a promotional video. As a non-profit group, they did not have the funds to hire professional marketers. A team of SLCC Tech Writing students agreed to take on the project. Meeting in a conference room down the hall from their regular classroom, the students worked with the Ahunas (including Grandpa Joe, who started their dance group and had very strong opinions about finding just the right fiery flame image for their logo) until the heart and soul of the Ahuna Ohana dance troupe could be proudly displayed online. This is an example of the countless ways students can combine service and learning to gain valuable skills that will make them more employable, help them have an impact, and come away with a sense of satisfaction knowing they truly helped someone who needed them.

There are many more examples. Did you know SLCC English students have done service, writing, and/or presentations for countless non-profit organizations and schools in our community? We have been involved with the United Way, the Utah Food Bank, Utah Food Rising, Catholic Community Services, Tree Utah, and so many more! For those who really get excited about service and learning, our College even has an Engaged Scholar program for students who want to do 100 hours of service over the course of their entire degree and graduate with special honors! We also offer alternative break trips to places like Seattle, San Francisco, and Best Friends Animal Society in Kanab for students who want to serve during spring break and reflect on the issues that we can do something about, such as food insecurity, homelessness, environmental preservation, and helping animals in need. Writing and reflection help us make these experiences into artifacts that show we are, indeed, good citizens.

But let’s face it—being a good citizen doesn’t always help us make rent, or have enough money to see a movie. Did you know, though, that service learning actually enhances student learning, and that it leads to greater employment opportunities? Being a good citizen, in other words, can actually help you get a higher GPA and be a more attractive candidate to not only prospective employers, but also to transfer institutions if you plan to pursue additional education after your current degree. Where’s the proof of this? Let’s take a look at some research.

What does national research tell us about the employability of students trained in community-based experiential learning and problem solving? The American Association of Community Colleges (AACC) commissioned Hart Research Associates to survey 400 employers from organizations with a minimum of twenty-five employees, at least 25% of whom have degrees from either two-year or four-year schools, with the goal of identifying learning outcomes favored in today’s economy, including the importance of applied learning experiences and project-based learning (2015, p. 1). Their findings were as follows:

Nearly all employers (96%) agree that, regardless of their chosen field of study, all students should have experiences in college that teach them how to solve problems with people whose views are different from their own, including 59% who strongly agree with this statement. Large proportions of employers also agree that that all students, regardless of their chosen field of study, should gain an understanding of democratic institutions and values (87%), take courses that build the civic knowledge, skills, and judgment essential for contributing to a democratic society (86%), acquire broad knowledge in the liberal arts and sciences (78%), and gain intercultural skills and an understanding of societies outside the United States (78%). (2015, p. 2)

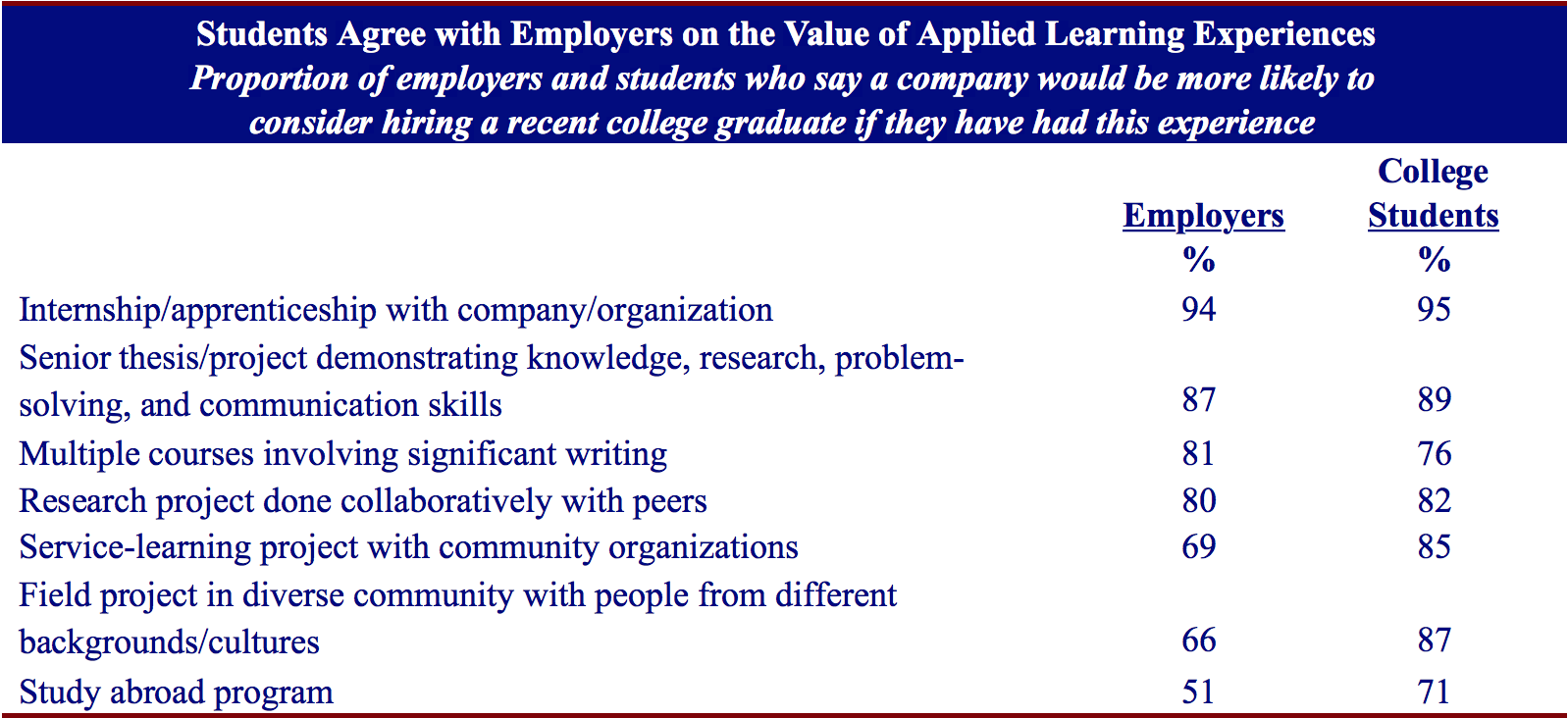

Furthermore, a significant majority of employers surveyed by Hart Research Associates indicated they would be more likely to hire a recent graduate who has completed various types of “applied and engaged learning experiences—such as a comprehensive senior project, a collaborative research project, a field-based project with people from other backgrounds, or a community-based or service-learning project” (AACC p. 7).

Given that employers value the outcomes and experiences service-learning can provide, what do students say about the importance of these concepts? The study mentioned above discusses how in 2013 Hart Research Associates surveyed more than 600 college students, including 158 community college students who planned to earn their associate degree or transfer to a university (2015, p. 1). Their findings were as follows (p. 8):

Importantly, both employers and students saw the need for improvement in providing students with a wide range of knowledge and skills that apply to their fields (p. 9).

Similarly, a report from Community Learning Partnership, a national network of community change–studies programs based in community colleges in partnership with local non-profit and civic organizations, tells us that students trained as community organizers demonstrate the following strengths:

- Definable duties, as well as a skill set, knowledge base, and worker characteristics that influence their ability to do their jobs successfully.

- Cross-sector skills that they can apply to a range of job categories.

- Experience with hands-on practice, a capacity for self-reflection, and access to mentoring by experienced organizers.

Academic programs can also make a particular contribution to supporting the knowledge base that organizers need, something that training programs that focus on skills and tactics generally do not emphasize (2013, p. 1).

It’s all good, you say, but that’s for you humanities types. I’m in the sciences! I plan to study chemistry, or math, or engineering, so writing for community change doesn’t really apply to my field or my future. Hold up . . . it does! Issues of social justice have become integral parts of the curriculum in many disciplines. This comes not only from concern for the well-being of society, but because studying issues of social justice delivers skills and a knowledge base that helps students be hired, succeed at their jobs, and succeed in post-graduate education. Students of disciplines that are traditionally associated with issues of peace and justice such as political science, communication, and social work will most certainly benefit from service-based writing. Yet a student of any discipline can stand to benefit from this opportunity. Examples of this can be seen in science fields such as medicine, psychology, and natural resource management.

In 2015, the Association of American Medical Colleges unveiled the new MCAT (Medical College Admission Test), which all prospective medical students must complete to apply to medical school (AAMC, 2015). The largest change to the test was making up to a quarter of it include content involving social and psychological principles. These can be seen in the test’s “Foundational Concepts” 6–10. Examples of social justice are seen in Foundational Concept 9, “Cultural and social differences influence well-being” and Foundational Concept 10, “Social stratification and access to resources influence well-being” (AAMC, 2015). The purpose of incorporating these concepts into the required curricula of all pre-med students is to ensure that the next generation of medical doctors have social and cultural understanding around issues of socioeconomic status, race, religion, gender, and other social justice issues.

While it is generally recommended that students take at least one introductory psychology and introductory sociology course in order to learn this, many students are likely to wish to engage in the material at a deeper level. This is not a new phenomenon in the medical disciplines, as shown by programs like Doctors Without Borders, which have incorporated social justice into their mission already (“Neglected People,” 2015). Students who go into healthcare come to it through many undergraduate majors including biology, psychology, chemistry, and more. Service-based writing would be applicable and desirable to students intending on a career in healthcare, regardless of their major.

The field of psychology, and all of its sub-disciplines, has always had a social justice component, although it was not always in the forefront of the field. But now, the APA (American Psychological Association) and APS (Association for Psychological Science) have, in their own ways, changed the field to focus on and advocate for research and application of social justice issues in the field as a whole (Vasquez, 2012; Meyers, 2007). Salt Lake Community College offers an Associates in psychology and we know that many more General Studies students will go on to complete a Bachelor’s or higher degree in psychology, as it is one of the largest undergraduate majors in the United States (Casselman, 2014).

Natural and cultural resource management and outdoor recreation are predominant areas of employment in Utah and the American West (see USAJOBS.gov for a clearinghouse of all federal job opportunities). Occupations vary from rangers working within our national parks to field biologists to agriculture. Many of our students hope to and will find themselves in these types of fields through a number of disciplines. Resource management and outdoor recreation aren’t just about the outdoors, though; they include human factors. And these disciplines, in both research and practice, have been incorporating the cultural, economic, and social needs of people into their management plans. What these fields need are more people trained in social justice awareness and in the human component of resource management. For one example of social justice conflict in park management, see a recent article from Al Jazeera America on the displacement of indigenous people in the name of conservation (Lewis, 2015, August 14).

Writing for community change via a service-learning experience would be applicable and navigable by any student in these types of science disciplines who wishes to dive deeper into these issues as they are seen in their fields. All of these fields are specifically asking for employees with the traits and skills that we hope to create at SLCC.

Hey, not everyone loves English classes or writing; we get that. Sometimes even professional writers hate writing! But since we all need writing for classes, everyday life, and career success, why not make it meaningful writing that helps create community change? Don’t take our word for it; try service-learning for yourself and see how the satisfaction of knowing you made a difference helps all the stress from studying, work, bills, balancing your life, and catching your breath fade away long enough to make you smile. ☺

A NOTE ON JOBS IN UTAH

Given that today’s employers value community organizing, leadership, public relations skills, critical thinking, effective communication, and cultural awareness, what is the value of these traits within our state? It turns out, Utah’s non-profit sector offers significant employment opportunities. As of 2015, jobs in the Utah non-profit sector included positions such as:

- Development (fundraising) specialist

- Childhood development specialist

- Program leader

- Program coordinator

- Placement specialist

- Military mentor

- Support services staff

- Case manager

- Speech pathologist

- Children’s group staff

- Executive director

- Administrative assistant

- Disaster preparedness educator

- Teaching assistant

- Education fellow

- Production clerk

- Independent living trainer

- Therapist

- Conference interns

- Social workers

- Treatment center support staff

- Community connections specialist

- Behavior counselor

- Food drive specialist

- Education specialist

- Job coach

- Veteran’s residential program manager

- Speaker recruiter

- Grants administrator

- Clinical coordinator

- Director of human resources

- National Ability Center ski/snowboard instructors

- Childcare worker

- Spanish-speaking family educator

- Behavior analyst

- Clinical supervisor

- Physician’s assistant

- Teen center staff

- Classroom aide

- Certified nursing assistant

- Literacy specialist

- Marketing specialist

- Volunteer coordinator

- Animal rescue staff

- Finance director

- Intake advisor

- Housing specialist

- Youth development professional

- Health education coordinator

- Resource development

- Community investment advisor

- Physical therapist

- Occupational therapist

- Cook

- Prevention specialist

- Employment specialist

- After-school program leader

- Family resource facilitator

- Nutrition supervisor

- Computer skills instructor

- IT

- Healthcare navigator

- Billing specialist

- Accessibility design coordinator

- Substance abuse specialist

- Disabilities and mental health coordinator

- Crisis worker

- Graphic design and technology associate

- Children’s advocate

- Special education paraprofessional

- Medical interpreter

- S.T.E.M program manager

- Veterinary technician

- Health policy analyst

- Accountant

- Business manager

- Outdoor education

- Youth mentoring specialist

- Youth garden program director

- Events coordinator

- Communications

- Transportation services manager

- Program and research coordinator

- American Indian specialist

- Service coordinator

- Continuum of care planner

References

Association of American Colleges & Universities. (2015). Falling short? College learning and career success selected findings from online surveys of employers and college students. Hart Research Associates.

Association of American Medical Colleges (2015). What’s on the MCAT2015 exam? Retrieved from https://www.aamc.org/students/services/343550/mcat2015.html#psbb on Sept 1st, 2015

Boyer, E. (1996). The Scholarship of Engagement. Journal of Public Service & Outreach, 1(1) 11-21.

Casselman, B. (2014, Sept 12th) The economic guide to picking a major. FiveThirtyEight Retrieved from http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-economic-guide-to-picking-a-college-major/ on Sept. 1st, 2015.

Community Learning Partnership. (2013). Listening—building—making change: job profile of a community organizer.

Doctors Without Borders (2015). Neglected people. Retrieved from http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/our-work/humanitarian-issues/neglected-people on Sept 1st, 2015.

Lewis, R. (2015, August 14th) “Violent displacement’ in the name of conservation must end, group says. Al Jazeera America. Retreived from http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/8/14/american-conservation-hurts-biodiversity-natives.html on Sept 1st, 2015.

Myers, S.A. (2007) Putting social justice in practice in psychology courses. Observer, 20(9) Retrieved from http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/publications/observer/2007/october-07/putting-social-justice-into-practice-in-psychology-courses.html on Sept 1st, 2015

Vasquez, M.J.T. (2012). Psychology and social justice: Why we do what we do. American Psychologist, 67(5) 337-46.