42 Movies Explain the World (of Writing)

Nikki Mantyla

Movie clips are one of my favorite teaching techniques. For example, to emphasize the importance of audience in an argument, I love to show the rainy scene from Focus Features’ Pride and Prejudice in which rich Mr. Darcy makes the claim that poor Lizzy should marry him. His reason is that he loves her “most ardently” and the evidence is his agony.

But Lizzy says whoop-dee-doo.

Despite the complications of British accents, archaic phrasing, and speedy dialogue, we get the idea: claim, reasons, and evidence aren’t enough if we haven’t considered the audience’s values. Lizzy isn’t the type to swoon at money or any old declaration of love. In contrast, when Darcy comes back with a humbler-voiced letter addressing her objections, it’s much more effective at persuading her to trust him.

By seeing it and hearing it as a movie clip, we remember the concept better. Who’s going to forget that intense of a proposal gone wrong? And hopefully the next time we sit down to write, we’ll think more about our audience’s beliefs, opinions, objections, etc.

My goal with this article is along those lines: to use movie clips and the movie-making process (which I would argue mirrors any type of composition process) to present writing concepts in memorable ways. We know focused reading can expand our repertoire of writing moves; now let’s see how analyzing the rhetorical strategies of cinema can improve our understanding of ideas, organization, voice, word choice, sentence fluency, and conventions—and translate into better writing from top to bottom.

IDEAS

How often have you been enticed by the premise (the idea) of a movie, only to have it fail to meet your expectations? Isn’t it wild that an idea can have so much potential and then totally flop if that potential isn’t developed?

Pixar is a movie producer that really sets the standard here, refining their ideas until they hit peak potential. For example, the premise for Ratatouille—a rat who wants to be a gourmet chef—was first pitched in 2000. By the fall of 2004, the script still wasn’t palatable enough. As one entertainment news hound put it,

While individual elements of the film … were admittedly charming and quite entertaining, its narrative as a whole fell flat. You never really got caught up in Remy’s quest to become one of the greatest chefs in France. … [The director and his] story team were then sent back to their drawing boards with some very specific orders: Make the story stronger and make us really care about the characters’ struggles. (Hill para. 11–12)

The team had to completely revamp until they had a story and characters—fiction’s biggest idea ingredients—that would deliver. Pixar even brought a second director on board to come up with a new vision. The effort paid off: Ratatouille went on to win the 2008 Oscar for Best Animated Feature Film.

Pixar believes that story is king, so they don’t settle for mediocre. Even with amazing computer-animated visual effects, movies need solid ideas first.

What makes ideas solid?

Think about how well your favorite movies do the following:

- excite/entice you

- provide something/someone to care about

- delve deep into the premise

- deliver on expectations

- resonate with you

These five criteria apply to all genres of writing. Consider the Pride and Prejudice clip above with its failed proposal: the idea of marrying Darcy did not entice Lizzy, did not offer her a fiancé she would care about, did not delve into the deeper issues she needed addressed, and did not meet her expectations for a good match—even though at the end we can see some emotional resonance. One out of five wasn’t enough for Lizzy.

But like Ratatouille did, Darcy is able to overcome his flaws—and so can we. Step by step he corrects each problem: addressing the issues thoroughly, making himself more likeable, exceeding her expectations, and becoming absolutely enticing to her. As we do the same, with our particular audience in mind, our writing can likewise win over our readers.

ORGANIZATION

Once we’ve got winning ideas, the next arena is organization. Great building blocks (fully developed ideas) won’t do as much good if they aren’t arranged well. Ideal arrangements match natural human expectations, and these expectations, believe it or not, are based on our brain’s programmed preference toward storytelling.

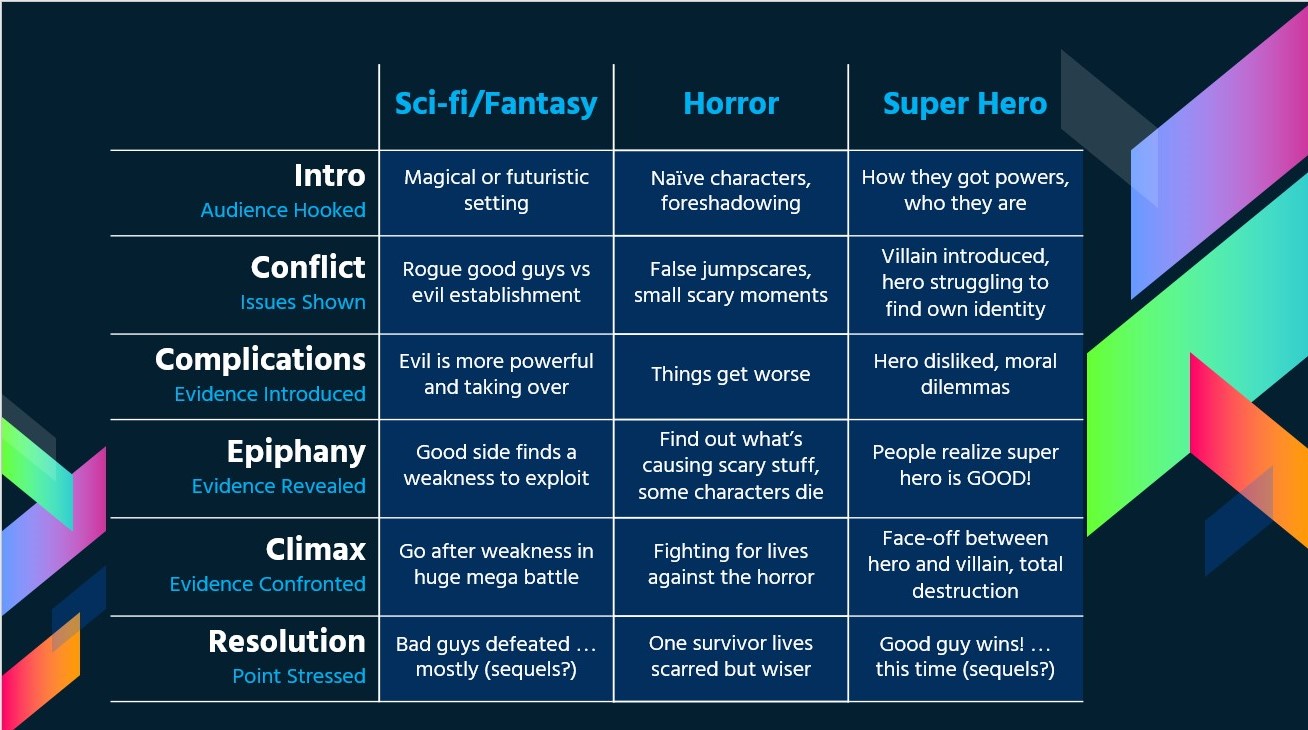

First, consider the basic six-step outline of storytelling: intro, conflict, complications, epiphany, climax, and resolution. Then look at how familiar movie genres use these steps:

As the slide above shows, each step has a purpose that applies to more than just storytelling.

Proceed step by step through each purpose to achieve ideal organization:

- INTRO ― hook your audience

- CONFLICT ― show what the big issues are

- COMPLICATIONS ― introduce the type of evidence/solution needed

- EPIPHANY ― reveal the evidence/solution

- CLIMAX ― explain/apply the evidence

- RESOLUTION ― stress the point

From hook to resolution, the organization builds the tension as it proceeds, keeping the audience in suspense for the final reveal. It’s why our ears perk up when someone starts a story. We want to know what happens. And that hard-wiring is why story-based organization is most effective—even beyond story genres.

For example, a recipe might hook us with the name and a great photo and a description of its yumminess. The main conflict/hurdle will be gathering the ingredients, so those are usually listed next. The complications are yield and time involved, often spelled out before we get to the steps that reveal why the dish takes so long to prepare. The epiphany is the steps themselves (“Oh! That’s how you make it!”). The climax is often the final step of baking/simmering/etc (when we’ll wait to see if the recipe worked). Finally, the resolution could be tips on how to serve the finished dish.

Good organization moves the ideas forward by creating momentum that carries us to the resolution. Nifty, huh?

VOICE

The popular indie flick Juno, which won an Oscar for Diablo Cody’s brilliant screenwriting, might be a perfect way to begin understanding voice. Just check out the trailer:

Voice is pretty much viewpoint, personality, and tone squashed together. It’s what gives a piece of writing its overall feel.

A good voice should be four things:

- strong

- appealing

- appropriate

- consistent

I’ve heard dissenters claim that Juno’s voice is too unrealistic and too exaggerated, but even an over-the-top voice can be awesome, so long as it meets the four criteria above.

Satire is one example of exaggerated voice. Writers attempting it must consider their situation and whether or not satire is a strong way to make their point, whether or not it’s appropriate for their topic, whether or not they can make it appealing, and whether or not they can maintain a consistent voice throughout the piece.

The last trait, consistency, doesn’t mean you can’t pull off a range of emotion, from funny to tragic. Juno manages to. I cry every time I watch it, and I laugh at the great lines, and I get angry at a certain character who will not be named (since it’d be a spoiler). Those disparate emotions all fit in the movie because they’re brought together by the same quirky, complex point of view: Juno’s.

To understand how that translates into writing, take a look at the examples below showing how various nonfiction genres also adopt a particular voice.

From Sharon Begley’s report, “Why Your Brain Never Really Rests”:

Oops. Neuroscience is having its dark-energy moment, feeling as chagrined as astronomers who belatedly realized that the cosmos is awash in more invisible matter and mysterious (“dark”) energy than make up the atoms in all the stars, planets, nebulae, and galaxies. For it turns out that when someone is just lying still and the mind is blank, neurons are chattering away like Twitter addicts. (para. 2)

From Jason Gay’s set of New Year’s resolution tips, “27 Rules of Conquering the Gym”:

This is the time of year when even people who hate the gym think about going to the gym. Many of us are still digesting whole floors of gingerbread houses, and jeans that fit comfortably in October are now a denim humiliation. (para. 1)

From Chris Jones’s ESPN profile of Zac Sunderland:

The crossing was the last great hurdle in his quest to be the youngest person to sail solo around the world. It was a desolate, often windless stretch—4,278 nautical miles that, on a good day, he covered at just six nautical miles an hour. The math could make seasoned sailors talk to themselves, let alone a 17-year-old California kid who’d just realized he’d lost his radar. (para. 1)

In the first article, the voice is a snarky but enthralling; in the second, it’s self-deprecating and funny; and in the third, it’s sympathetic and tense. All three are strong voices, appropriate for the topic, appealing to their audience, and consistent throughout.

WORD CHOICE

While voice is the overarching feel, word choice is the specific, detailed texture. The big considerations of voice have to come first, and then you can sprinkle in the details.

It’s similar to how you choose actors for a movie based on the feel you want, and then you reinforce that feel with their costumes. The actors (and their skills) are the voice; the costumes (and the sets) are like word choice.

Again, both need to be appropriate for the piece. We don’t want gladiators wearing frilly dresses covered in bows (unless we’re creating a parody). We have to find the words that fit the texture we’re going for.

In the following excerpts from young-adult novels, notice how the individual words dress each unique character and setting like wardrobe and sets.

From James Dashner’s The Maze Runner:

He heard noises above—voices—and fear squeezed his chest.

“Look at that shank.”

“How old is he?”

“Looks like a klunk in a T-shirt.”

“You’re the klunk, shuck-face.”

“Dude, it smells like feet down there!”

“Hope you enjoyed the one-way trip, Greenie.”

“Ain’t no ticket back, bro.” (3)

From M. T. Anderson’s The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation: The Pox Party:

I was raised in a gaunt house with a garden; my earliest recollections are of floating lights in the apple-trees.

I recall, in the orchard behind the house, orbs of flames rising through the black boughs and branches; they climbed, spiritous, and flickered out; my mother squeezed my hand with delight. We stood near the door to the ice-chamber.

By the well, servants lit bubbles of gas on fire, clad in frockcoats of asbestos.

Around the orchard and gardens stood a wall of some height, designed to repel the glance of idle curiosity and to keep us all from slipping away and running for freedom; though that, of course, I did not yet understand.

How doth all that seeks to rise burn itself to nothing. (3)

From Laini Taylor’s Faeries of Dreamdark: Blackbringer:

“How you holding up, my feather?” she asked the crow she rode upon, stroking his sleek head with both hands.

“Like a leaf on a breeze,” he answered in his singsong voice. “A champagne bubble. A hovering hawk. A cloud! Nothing to it!”

“So you say. But I’m no tiny sprout anymore, Calypso, and sure you can’t carry me forever.”

“Piff! Ye weigh no more than a dust mouse, so hush yer spathering. ’Twill be a sore day for me when I can’t carry my ’Pie.” (4–5)

Each excerpt makes me want to keep going. Voice and word choice together bring writing to life as surely as actors, wardrobe, and sets in a movie.

While the above examples are from fictional works, that transformative effect can happen in any genre. Whether in fiction or nonfiction, you can potentially pen words that will outlast you, like this famous editorial from 1897, responding to eight-year-old Virginia O’Hanlon’s letter to The New York Sun, “Is There a Santa Claus?”:

Yes, VIRGINIA, there is a Santa Claus. He exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy. Alas! how dreary would be the world if there were no Santa Claus. It would be as dreary as if there were no VIRGINIAS. There would be no childlike faith then, no poetry, no romance to make tolerable this existence. We should have no enjoyment, except in sense and sight. The eternal light with which childhood fills the world would be extinguished. (para. 2)

Beautiful, right?

But of course, well-chosen words alone do not make good writing. It’s like Will Ferrell’s character in Bewitched blaming the wardrobe department for the failure of his latest movie. Yeah, maybe the Sherpa hats were ridiculous-looking, but even great costumes wouldn’t have made up for his terrible acting (the character’s, not Will Ferrell’s).

The newspaper snippet shows how a writer has to do everything we’ve discussed so far:

- Introduce a powerful idea ― comparing Santa Claus to joy

- Shape the organization ―

- Intro: “yes, Virginia”

- Conflict: existence of Santa Claus

- Complications: his connection to love, generosity, beauty etc

- Epiphany: without him the world is dreary

- Climax: facing how much goodness we would lose

- Resolution: childhood faith lights the world

- Find a perfect voice ― tone of wonder and sincerity appropriate for responding to a serious child’s question

- Choose the best words ― exist, abound, alas, childlike, enjoyment, eternal, light

Revising on only one level, such as only worrying about the words, wouldn’t be enough.

SENTENCE FLUENCY

Next, let’s try a little experiment of observation. As you watch this clip below from the movie Stranger Than Fiction, I want you to notice the cuts. Usually, we don’t—unless the film editors have done a poor job. Usually, the cuts are so natural that we easily shift from one angle to the next. But if you force yourself to notice, you can observe a lot about how they make it smooth.

For one thing, did you notice how Harold (Will Ferrell) walking around the store creates a sense of flow? If each shot had cut straight to him already in front of each guitar, it would be more jarring. Instead, they cut one angle as he starts to move away from a guitar and then pick up the next angle as he’s walking toward a new one. It creates flow between the shots, and the cuts become nearly invisible, leaving us to focus on the meaning of how the scene impacts the story.

Sentences have to be the same way. They have to flow so smoothly that we hardly notice them—unless to occasionally notice a sentence as breathtaking as a beautiful shot in a movie. Other than that, the sentences should simply be working together to feed us a story, piece by piece.

Look at how that happens in the following excerpt from Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book:

There was a hand in the darkness, and it held a knife. The knife had a handle of polished black bone, and a blade finer and sharper than any razor. If it sliced you, you might not even know you had been cut, not immediately.

The knife had done almost everything it was brought to that house to do, and both the blade and the handle were wet.

The street door was still open, just a little, where the knife and the man who held it had slipped in, and wisps of nighttime mist slithered and twined into the house through the open door. (2–5)

This passage is a great example of what is called the known–new contract, in which each sentence builds on the one before. Neil Gaiman begins with “there was” and then adds something new: “a hand in the darkness.” Then he refers to the hand as “it”—something now known—and adds the next new piece: a knife. The knife again (now known) leads us to its handle and blade (new). Notice how subtle changes reinforce this: when it’s new, it’s a knife, but once it’s known, it becomes the knife. The sentences are one long chain of known–new–known–new, flowing as smoothly as movie shots.

Creating that chain sounds tedious at first, but astute writers naturally point back to what’s known so that the sentence fluency is smooth. When they encounter an out-of-place sentence, they look for breaks in the known–new chain and add the necessary pieces to fix it.

Below is a nonfiction example from a sports article called “The Man in the Van” about baseball pitcher Daniel Norris. As you read the opening paragraph, pay attention to how the author takes you from one sentence to the next.

The future of the Toronto Blue Jays wakes up in a 1978 Volkswagen camper behind the dumpsters at a Wal-Mart and wonders if he has anything to eat. He rummages through a half-empty cooler until he finds a dozen eggs. “I’m not sure about these,” he says, removing three from the carton, studying them, smelling them and finally deciding it’s safe to eat them. While the eggs cook on a portable stove, he begins the morning ritual of cleaning his van, pulling the contents of his life into the parking lot. Out comes a surfboard. Out comes a subzero sleeping bag. Out comes his only pair of jeans and his handwritten journals. A curious shopper stops to watch. “Hiya,” Daniel Norris says, waving as the customer walks away into the store. Norris turns back to his eggs. “I’ve gotten used to people staring,” he says. (Saslow para. 1)

Did you catch the chain?

You might sum it up like this:

- wakes up in a van (known from title) and wonders what’s to eat (new)

- rummages for food (known) and finds eggs (new)

- starts cooking the eggs (known) and begins to clean (new)

- pulls out items to clean his van (both known) and sees a curious shopper stare (new)

- returns to cooking (known) and comments on the staring (known): he’s gotten used to it (new)

The end of one sentence, like “wonders if he has anything to eat,” connects us straight to the beginning of the next sentence: “He rummages through a half-empty cooler.” That way readers never feel lost—and probably don’t even notice the “cuts.” Like an editor splicing the shots, the author creates congruence from each sentence to the next so that they flow.

CONVENTIONS

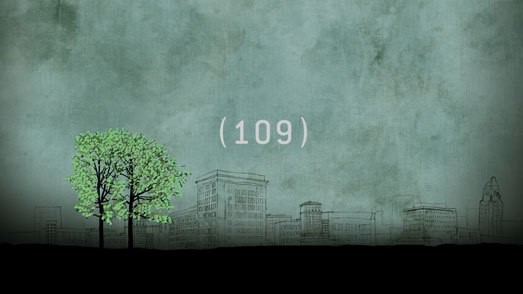

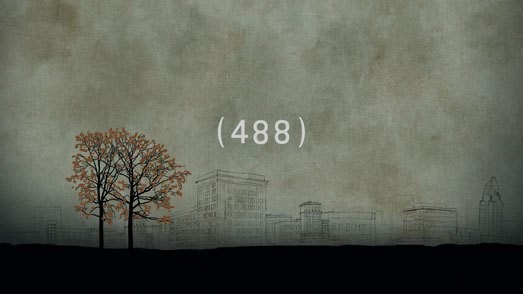

Finally, we get to the arena of visual effects—the stuff that makes movies look so cool. As a simple example, let’s examine the brief animation sequences sprinkled throughout the movie (500) Days of Summer. These scene-changes were some of the very last things to be completed for the movie, and they help orient viewers to the point in time of the next scene (within the 500 days).

Conventions in writing are like everything that happens after the footage has been pieced together. Once all the frames have been sequenced—all our sentences strung—the last job is to coordinate the extra pieces that will help pull the whole movie together. These last additions are everything from overall design down to punctuation. Notice how even the title of the movie coordinates with the scene-changes by placing the number in parentheses—a punctuation choice that makes the isolated numbers on the screen simple to understand.

Similarly, the occasional split screen in the movie is an unusual convention that’s both appealing and clarifying for these scenes. By playing Tom’s expectations and reality side by side, the split screen ups the heartbreak.

Larger convention choices like that also happen in writing when we tailor our images, layout, and so on to make the point clearer. And sometimes they can be unconventional, like the four pages in Stephenie Meyer’s novel New Moon with only one word each: the name of a month. That method for showing the empty-feeling passage of time was so effective for the story that they used it in the movie too.

And of course, as writers, we also have to coordinate every little piece of punctuation for clarity and appeal. Just like we wouldn’t want a boom mic hanging down into the shots, distracting from the movie, we want our conventions to work for us, not against us.

Notice the conventions this article uses for aesthetic appeal and content clarification:

- relevant videos

- text boxes with key points

- eye-catching pictures

- headings

- lists

- frequent paragraph breaks

- bold terms

- em dashes for emphasis

- parentheses for interesting side notes

In the end, the job of the six traits we’ve examined is to make our grand ideas really shine and leave our audience with plenty of valuable takeaways, so they won’t walk away saying whoop-dee-doo.

Works Cited

(500) Days of Summer. Dir. Marc Webb. Perf. Zooey Deschanel, Joseph Gordon-Levitt. Fox Searchlight, 2009. Film.

Anderson, M. T. The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation, Volume 1: The Pox Party. Massachusetts: Candlewick P, 2006. Print.

Begley, Sharon. “Why Your Brain Never Really Rests.” Newsweek. Newsweek LLC, 30 May 2010. Web.

Bewitched. Dir. Nora Ephron. Perf. Nicole Kidman, Will Ferrell. Columbia TriStar, 2005. Film.

Dashner, James. The Maze Runner. New York: Delacorte, 2009. Print.

Gaiman, Neil. The Graveyard Book. New York: HarperCollins, 2008. Print.

Gay, Jason. “27 Rules of Conquering the Gym.” Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones Inc, 5 Jan 2012. Web.

Gladiator. Dir. Ridley Scott. Perf. Russell Crowe. Dreamworks, 2000. Film.

Hill, Jim. “Why For Did Disney Struggle to Come Up with a Marketing Campaign for Pixar’s Latest Picture? Because the Mouse Wasn’t Originally Supposed to Release ‘Ratatouille.'” Jim Hill Media. 27 Jun 2007. Web.

“Is There a Santa Claus?” The New York Sun. TWO SL LLC, 21 Sep 1897. Reprinted 21 Dec 2012. Editorial.

Jones, Chris. “Do Hard Things.” ESPN Magazine. ESPN Inc, 15 Jun 2009. Print.

Juno. Dir. Jason Reitman. Perf. Ellen Page. Fox Searchlight, 2007. Film.

Martel, Yann. Life of Pi. Orlando: Harcourt, 2001. Print.

Meyer, Stephenie. New Moon. New York: Little Brown, 2006. Print.

My Fair Lady. Dir. George Cukor. Perf. Audrey Hepburn, Rex Harrison. Warner Bros, 1964. Film.

Pride and Prejudice. Dir. Joe Wright. Perf. Keira Knightley, Matthew Macfadyen. Focus Features, 2005. Film.

Ratatouille. Dir. Brad Bird, Jan Pinkava. Perf. Patton Oswalt. Pixar, 2007. Animated film.

Saslow, Eli. “The Man in the Van.” ESPN Magazine. ESPN Inc, 5 Mar 2015. Web.

Stranger Than Fiction. Dir. Marc Forster. Perf. Will Ferrell. Columbia Pictures, 2006. Film.

Tailor, Laini. Faeries of Dreamdark: Blackbringer. New York: Penguin, 2007. Print.