11 Monstrous Rhetoric: The Beasts We Feed

Ann Fillmore

- Do Monsters Really Exist?

- What Creates a Monster?

- Monsters Serve Many Purposes.

- Monsters Adapt to the Needs of a Situation.

- What Do Monsters Reveal?

- What Can Monsters Teach Us?

“Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.” ―Friedrich Nietzsche

I love monsters. I love scary stories and monster movies. I love classic monsters and contemporary monsters. Spine-tingling stories are a part of our history and are passed down from generation to generation as folklore and pop culture. Humans are fascinated with monsters, but why? What is the connection? What makes a monster?

The word monster is a derivative of the Latin word monstrum, which is defined as “that which reveals, that which warns” (Cohen 4). This definition sparked my interest since I teach rhetoric and writing, and I ponder such things. And, I found myself asking, “What do monsters reveal to us? What can monsters teach us?”

In the article “Monster Culture: Seven Theses,” medieval scholar Jeffrey Jerome Cohen presents several criteria (theses) about what makes a monster. His work not only captivated my attention but has helped me to appreciate how monsters can be an effective tool for understanding rhetoric and discourse today. “How?” you might ask. Because monsters show us that language matters.

DO MONSTERS REALLY EXIST?

Yes. What is a monster? It depends on the audience.

Monsters exist in many forms. They can be literal or metaphorical and can manifest as people, places, things, and even ideas. Monsters are “outsiders” that symbolize the fears, taboos, and values of a culture. They emerge as “a construct and a projection” of the cultures who creates and perpetuate them (Cohen 4). Therefore, a monster is a part of folklore that represents different things to different people. For example, when I think of a dragon, I think of a scaly, fire-breathing creature that burns villages (like Smaug in the book The Hobbit). However, in China, dragons represent good fortune and luck.

By examining how people use language to do things, be things, and make things in the world, we gain insight into a culture. Cohen argues that all monsters are, in fact, “texts” and that we can more fully understand a culture by “reading” its monsters. Monsters, old and new, are a reflection of their audience during specific moments in time. Therefore, “every monster is in this way a double-narrative, two living stories: one that describes how the monster came to be, and another, its testimony, detailing what cultural use the monster serves” (13).

WHAT CREATES A MONSTER?

We do.

Monsters are rhetorical. A monster lives in the way we tell its story. It’s all in the delivery; as we can see from the example above, those who fear dragons draw on a diction that generates emotions of fear, whereas societies who value dragons employ a discourse to portray creatures of wisdom and nobility, worthy of celebration. Language matters.

Modern examples are not difficult to find. Think of how people discuss current issues. For instance, climate change is a beast that ravages the landscapes, flora, and fauna, resulting in extinctions and extreme natural disasters worldwide. Some frame climate change as a conspiracy (climate change is not the monster, but those who claim so are) and others argue climate change as fact (climate change as the monster).

We can also see this in how people manipulate language to frame Covid-19 as political. For some, it’s a monstrous pandemic, a tragic circumstance that has devastated global economic, health, and social systems. For others, the virus was an act of carelessness or mal intent by the Chinese. They choose to cast blame at this nation with terms such as “Chinese virus” and #kungflu. The spread of pejorative language has lead to a racializing of the virus and a profiling of individuals of Asian descent. And who says language doesn’t matter?

MONSTERS SERVE MANY PURPOSES.

Every culture has distinct values, customs, and ideals, and monsters are often used as a rhetorical tool for enforcing the norm. One move often associated with monsters is the use of fear because fear can shape behavior and attention to more desired actions. For example, parents in the U.S. lay on the pathos (an appeal to emotions) in order to “encourage” their kids into behaving during the holiday season. Parents threaten that Santa is always watching and won’t deliver presents if a child’s name is on the naughty list. In this narrative, we see that the monster (yes, Santa) is used to warn children against “crossing the line” and to behave in a manner that is expected. The story brings consequences to life for children and serves as a useful behavioral tool for parents because it gives them control and power.

What does this monster tell us about American culture? It reveals many things if we “read” into it. One could see that though Christmas is a traditional Christian holiday, it has morphed into a commercial holiday. One could infer that children are part of this consumerism and parents leverage merchandise and happiness (Christmas morning) for control. It could also prompt us to examine why certain behaviors are considered “naughty” or “nice” in American culture and how these norms developed. It could also illustrate that children in the U.S. are highly emotional, and that pathos can be an effective rhetorical tool for manipulation. To be fair, Santa is also a “monster” who brings cheer, celebration, and reward. In this way, we can see the purpose of the double narrative for children and parents.

MONSTERS ADAPT TO THE NEEDS OF THE SITUATION.

Monsters never truly die. Cohen claims that a monster can survive “cultural shifts” and that monsters are continually adapted and revised to meet the needs of the situation. In this way, a monster can “return in slightly different clothing, each time to be read against contemporary social movements” that give them “new life in a modern rewriting” (Cohen 5).

Monsters possess the ability to escape only to return at a later date (another opportune moment) to haunt again. Think of the movie franchise Friday the 13th. How many times will Jason Voorhees return from the dead to torture the poor camp counselors at Camp Crystal Lake? Even his masks have endured cultural shifts to more effectively scare contemporary audiences.

Likewise, language endures, and the stories we write will live on (and be revised) long after we are gone. For example, during the late 1600s, witches were feared, tortured, and killed in Colonial America. Puritans considered “black magic” to be an evil abomination of God. Their accusatory language caused mass hysteria in Salem, Massachusetts, and consequently, resulted in punishment, torture, and execution of women and men. However, in modern times, we have reframed the narratives to meet the shifting cultural landscape. We depict witches and wizards as beings (not quite humans, but not quite monsters) who fight evil and social injustice (think Harry Potter). Authors have created a successful pop culture of witchcraft and magic to be entertaining, heroic, and lucrative in print, television, and cinema (Hocus Pocus, Maleficent, Bewitched, The Craft, The Magicians, etc.) Doing so moves the audience to envy their magic and relate to the human challenges the characters face.

As Cohen puts it, cultural shifts are all about timing: “The monster is born at [a] metaphoric crossroads, as an embodiment of a certain cultural moment — of a time, a feeling, and a place” (4). For example, think of the way we’ve seen language give “new life” to the face mask in the U.S. What was once a simple device used for protection (and seldom talked about) has been recast to tell a story of political affiliation and protest during the Covid-19 pandemic. For some, the face mask is considered a monster with devious intentions to take away our rights. For others, the face mask is a hero that intercepts dangerous germs and keeps people safe. This double narrative shapes meaning, identity, and action (to wear or not to wear?). How will we feel about face masks in the future? Only time will tell.

WHAT DO MONSTERS REVEAL?

Humans are the real monsters, and language is our weapon.

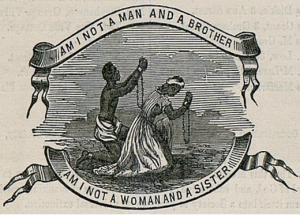

Monstrous rhetoric is used to justify law, policy, and punishment (Cohen 11). For example, the enslavement of Africans and their descendants was argued as “crucial” for physical labor, and vociferous supporters argued that emancipation could lead to economic and social collapse. When we erase the violence from the narrative, we fail to convey the true story: the devastation of family separation, the pain of stripping away names and identities, the denial of basic human rights, and the frustration and grief the slaves endured as they were forbidden from using their heritage languages. The fragmented history of slavery has lead to stories being lost, and those that we have are whitewashed (told by white people with the intent to conceal).

Along the same line, Cohen argues that a walk through the history books shows us how deceptive rhetoric (written strategically by those with power) frequently dehumanizes those who are different, labels and “others” them as monsters, and serves as a scapegoat to justify “cultural, political, ideological differences and biases” (7). Many people have chosen to portray Native Americans as uneducated, anti-Christian savages; black people as criminals; and Muslims as terrorists. Women, immigrants, and people of color are underrepresented and marginalized, which leaves a fragmented history of civilization.

One doesn’t have to stretch very far to think of the Holocaust as another example. In his book titled, Mein Kampf (My Struggle), Adolf Hitler wrote, “Was there any form of filth or profligacy, particularly in cultural life, without at least one Jew involved in it? If you cut even cautiously into such an abscess, you found, like a maggot in a rotting body — often dazzled by the sudden light — a Kike.” (Kike is an offensive word for a Jewish person). The Nazi propaganda poster with the Jewish star reads, “Whoever wears this symbol is an enemy of our people.”

In his article “Fighting Words: What We Can Learn from Hitler’s Hyperbole,” Dr. Michael Blain paints a dismal picture of how Hitler used “fighting words” in his speeches and propaganda in order to convince German youth to exterminate millions of Jewish people. Blain argues,

The violence and cruelty so characteristic of our species is rooted in the resources of hyperbolic [exaggerated] language. Hitler seems to have turned his “maggot” aphorism into a strategy to achieve his political objectives. He turned the Jews into racial “monsters,” and, in fighting Jews, he became “monstrous.” … The Jews and Slavs were described as the murderers of everything the German masses identified as good, true, and beautiful. The Nazis talked themselves and then the German people into a war of revenge against “murderous” enemies, a war to determine who would govern Europe for the next thousand years. Hitler conceived the goals of the Nationalist Socialist movement in millennial terms. (258)

Indeed language matters, and it can literally kill people.

WHAT CAN MONSTERS TEACH US?

Monsters offer an opportunity for reflection, revision, and action. Cohen’s final message to readers is that we should embrace our monsters as a learning opportunity because they “bring not just a fuller knowledge of our place in history and the history of knowing our place, but they bear self-knowledge — human knowledge — and a discourse all the more sacred. … These monsters ask us how we perceive the world, and how we have misrepresented what we have attempted to place. … They ask us why we have created them” (20). The monster “seeks out its author to demand its d’etre [reason for being] — and to bear witness to the fact it could have been constructed otherwise” (12).

Monsters require a rhetorical analysis, and rhetoric is “a way to investigate, understand, and use language” to analyze our monsters. This is not easy work. As SLCC English professors Chris Blankenship and Justin Jory write in their article “Language Matters,” “Working with language is difficult and it’s messy. It’s a skill you have to learn and practice [and] rhetoric gives you a framework to make that process easier. It’s a method that you can use systematically as a way of revealing and handling the complexity of language.”

Monsters exemplify the narratives we live, and we have many different stories to tell. We all have monsters in our lives that haunt us. It’s an inescapable part of being human. And, we cannot forget that we are the narrators of history. As such, we will need to make very important choices. As SLCC professor Charlotte Howe says in her article “Writers Make Strategic Choices,” “If we want to be heard, understood, and perhaps even agreed with, we must make choices, develop strategies, and enact decisions that go beyond simply deciding what we want to say. We must choose the occasion — find just the right moment — to speak.”

Language matters. We can choose to be ethical, credible, and responsible with our messaging (ethos). We can choose to use inclusive language. We can choose to respect and acknowledge diversity. We can choose not to spread false or biased information. We can choose to accurately represent evidence. We can choose to “reevaluate our cultural assumptions … , our perception of difference, [and] our tolerance towards its expression” (Cohen 20).

Remember that monsters exist in many forms. And, what feeds them?

We do.

Works Cited

Blain, Michael. “Fighting Words: What We Can Learn from Hitler’s Hyperbole.” Symbolic Interaction, vol. 11, no. 2, 1988, pp. 257–276. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/si.1988.11.2.257. Accessed 8 Dec. 2020.

Blankenship, Chris and Jory, Justin. “Language Matters: A Rhetorical Look at Writing.” Open English at SLCC: Texts on Writing, Language, and Literacy. Pressbook. openenglishatslcc.pressbooks.com/chapter/language-matters-a-rhetorical-look-at-writing/. Accessed December 4, 2020.

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. “Monster Culture: Seven Theses.” Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996, pp. 3–25.

Howe, Charlotte. “Writers Make Strategic Choices.” Open English at SLCC: Texts on Writing, Language, and Literacy. Pressbook. openenglishatslcc.pressbooks.com/chapter/writers-make-strategic-choices/. Accessed November 27, 2020.

Word-cloud monster image created by the author on wordart.com.